The art of stealing

Art theft is worth £3bn a year, and the latest heist is one of the biggest ever. Andrew Johnson reports on the volatile trade in pictures, antiques and sculpture

A romantic aura hangs around the art thief, the gentleman burglar who evades the sophisticated security of the worlds' most glamorous museums – like Pierce Brosnan in The Thomas Crown Affair, or Dr No, the evil James Bond mastermind with a penchant for beauty.

The reality, of course, is somewhat different. There are no Mr Bigs with the manners of Noël Coward sitting in their crime-control bunkers with stolen Picassos, Monets and Van Goghs on the wall.

When an armed gang broke into the Emil Buehrle museum in Zurich last Sunday and made off with four paintings by Cézanne, Degas, Van Gogh and Monet, worth £82m – one of the biggest art raids ever – they certainly knew what they were looking for. It is unlikely, however, that they were stealing to the order of a New York crime boss who needed a few quality pictures to complete his new Manhattan loft conversion.

Art theft is big business. After drugs and weapons, it is the third most lucrative international criminal operation, according to the FBI, and it is thought to be worth around £3bn a year, and rising in line with the soaring value of art.

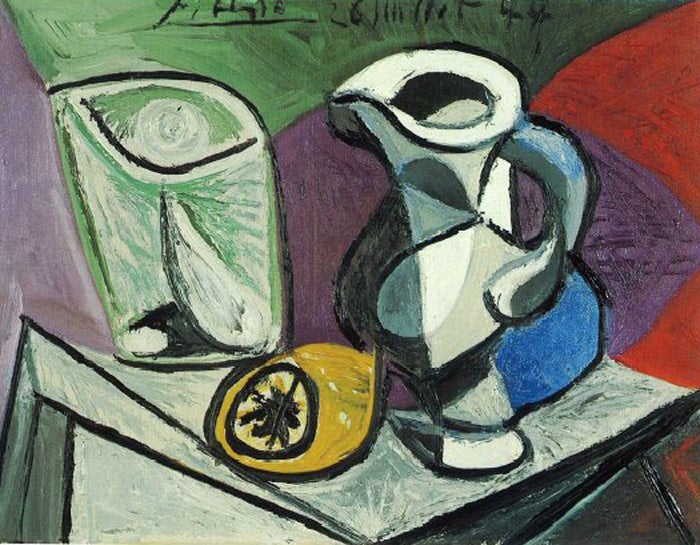

Only three days before Sunday's raid, two Picassos – Head of Horse and Glass and Pitcher – were lifted from an exhibition in the town of Pfaeffikon, near Zurich.

The next day Brazilian police recovered Picasso's Portrait of Suzanne Bloch in São Paulo, which had been stolen from the city's Museum of Art in December. Last February Picasso's granddaughter Diana Widmaier Picasso woke up in her Paris home to find two bright square patches on her living-room walls where her grandfather's Maya and the Doll and Portrait of Jacqueline, worth around £34m, used to hang.

According to the Art Loss Register, the London-based organisation that keeps a record of stolen art work, there are more than 7,500 works missing, including 572 Picassos, making the Spanish artist, who died in 1973, the most sought after name by criminals. Miró, Dali, Warhol and Matisse all make the dubious top 10.

The question is, however, what can Sunday's thieves do with paintings as well known as Cézanne's The Boy in a Red Vest, Degas' Count Lepic and his Daughters, Van Gogh's Chestnut in Bloom or Monet's Poppies Near Vetheuil?

According to Julian Radcliffe of the Art Loss Register, there are two options. The first is to keep the painting for a decade or longer in the hope it is forgotten about, then try and put it back on the market as a "sleeper". This is a work that has been passed on under a false attribution (wittingly or unwittingly) and is then rediscovered as the work of a major artist by a collector, dealer or auctioneer. If it stays in the underworld, it can be used as collateral for, say, drug deals, and it can pass through the hands of numerous criminals before it resurfaces. The other option is to try to ransom it.

"Our database makes it a lot more difficult to put works back on the market after a long time because we never take a work off the list," Mr Radcliffe said. "Seven works stolen in America in 1978, including a Cézanne, were all recovered by 2006. If used as collateral on drug deals, however, only a fraction of their true value is realised. Ransoms are rarely successful because there needs to be a pick-up and with intelligence nowadays the police often catch the thieves."

Much of the art ends up in northern Cyprus or Taiwan, because the islands are not officially countries, and have no extradition treaties.

"Only 15 to 30 per cent of high value paintings are recovered," Mr Radcliffe said. "Some, I'm sure, are sold to some unknown person who does not know what it is. Some of the sleepers coming on the market may have been bought innocently 100 years ago. Some, too hot to handle, are destroyed."

Detective Sergeant Vernon Ripley, of Scotland Yard's art and antiques unit, said stolen art was also used by gangs to circumvent the crackdown on international financial transactions. "It's increasingly difficult to take money across borders," he said. "It's much easier to smuggle objects.... Stolen coins are a particular concern. If one is worth £10,000 all a criminal has to do is put a few in his pockets.... Customs officers can't be expected to be art experts."

What else can happen to a stolen work is illustrated by the saga of two Turner paintings worth £50m stolen from the Tate in July 1994. The Serbian warlord Arkan was believed to be behind the theft of Shade and Darkness and Light and Colour while on loan to a Frankfurt museum. It is thought the paintings stayed in Germany, and were used for collateral in smuggling deals. In 1995 the thieves were arrested, but refused to divulge the paintings' whereabouts.

In 2000, six months after the assassination of Arkan, Shade and Darkness was handed to the then director of programmes at the Tate, Sandy Nairne. The recovery was kept secret until 2002 when Light and Colour also re-emerged after the Tate reportedly paid £3.5m to the German authorities. This allegedly went to pay a chain of informants, although the museum insisted that no ransom was paid.

High profile thefts are just the tip of the iceberg, Mr Radcliffe added. Most stolen art works are the more untraceable antiques and minor paintings stolen from stately homes, of which only 1 per cent or so are recovered.

A glimpse into the kinds of relatively low-value works stolen can be seen from the haul police officers found when they raided the £2m home of north London crime godfather Terry Adams in 2003. The details of the raid were only released in June last year after the Art Loss Register managed to trace the owners of £274,000 worth of stolen goods.

Among the "Aladdin's cave" of goods were a £2,000 Chinese lacquered writing bureau stolen in 1992 from Sherborne, Dorset, five pieces of Meissen porcelain worth £120,000 stolen from the Library Museum of the Freemasons in 1991 and 1996, a £60,000 pair of blue john cassolette vases taken from Asprey's auction house in 1996, plus several Henry Moore prints and Picasso etchings worth £35,000, stolen from the Marlborough galleries in London.

Thieves have hit on an even safer and possibly more lucrative seam of treasures – those that stand in Britain's streets and parks. Ian Leith of the Public Monuments and Sculpture Association (PMSA) estimates that thefts of public works of art have risen by around 500 per cent in the past two years. The most infamous examples are Henry Moore's £3m Reclining Figure, taken from the Moore Foundation in Hertfordshire in November 2005, and Watchers, by Lynn Chadwick, worth £300,000, stolen from Roehampton University's grounds in February 2006. A life-size bronze statue of Olympic athlete Steve Ovett was taken from Preston Park in Brighton last year and a 1.5 ton statue of a soldier was stolen in Nuneaton in 2006.

Stealing a two-ton sculpture such as the Henry Moore requires a flat-bed lorry and a crane, and a place to hide it – or melt it down. The scrap-metal value of the Moore would be around £6,000 – quite a poor return for the manpower and organisation needed. But if the bronze was used to make fake antiquities such as coins or small statues then there might be more profit in it. The Roehampton sculpture was cut up on site.

Mr Leith, however, believes there is also a market for stolen public art, and points out that while many of the works which go missing are bronze, some are stainless steel and stone. The problem is made worse by the lack of a national inventory or database of public work. "One piece of public art has been stolen every month for the last couple of years," he said. "The police think it's for the value of the bronze, but some of it is being stolen to order .... From the choice of artists, some form of criminal discrimination is evident and the value of copper – the main constituent of bronze – has quadrupled since 2003.

"The PMSA, a tiny charity, is the only organisation attempting to keep track of what has been lost. Paintings are over-defined, but what sculpture sits outdoors or in official stores is completely unknown."