Terrorists being released from UK prisons could 'slip through net' and carry out attacks, government warned

Exclusive: Prison officer brands government counterextremism policies ‘laughable’ amid crisis in UK jails

The growing number of terrorists being released from British prisons could “slip through the net” and attack because authorities do not have the capacity to monitor them, the government’s former extremism tsar has warned.

Ian Acheson, an ex-prison governor who reviewed Islamist extremism in the UK’s jails, said the record number of terrorists being locked up could accelerate radicalisation already taking place.

“There has been a problem for years and the organisation [HM Prison and Probation Service] has been asleep,” he told The Independent. “Islamist groups offer a very seductive message and if the prison doesn’t have an alternative, because it can’t offer a full regime and rehabilitation programmes, it’s a clown show.

“There is no capacity for staff to challenge ideologies – we have got ungoverned spaces and that’s where extremism thrives.”

A crisis driven by overcrowding, understaffing, disorder, violence and drugs came to a head this month as officers walked out in protest and the head of HM Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) resigned.

Meanwhile, the government’s part-privatisation of probation in 2014 has left a fractured system letting convicts offend again and again.

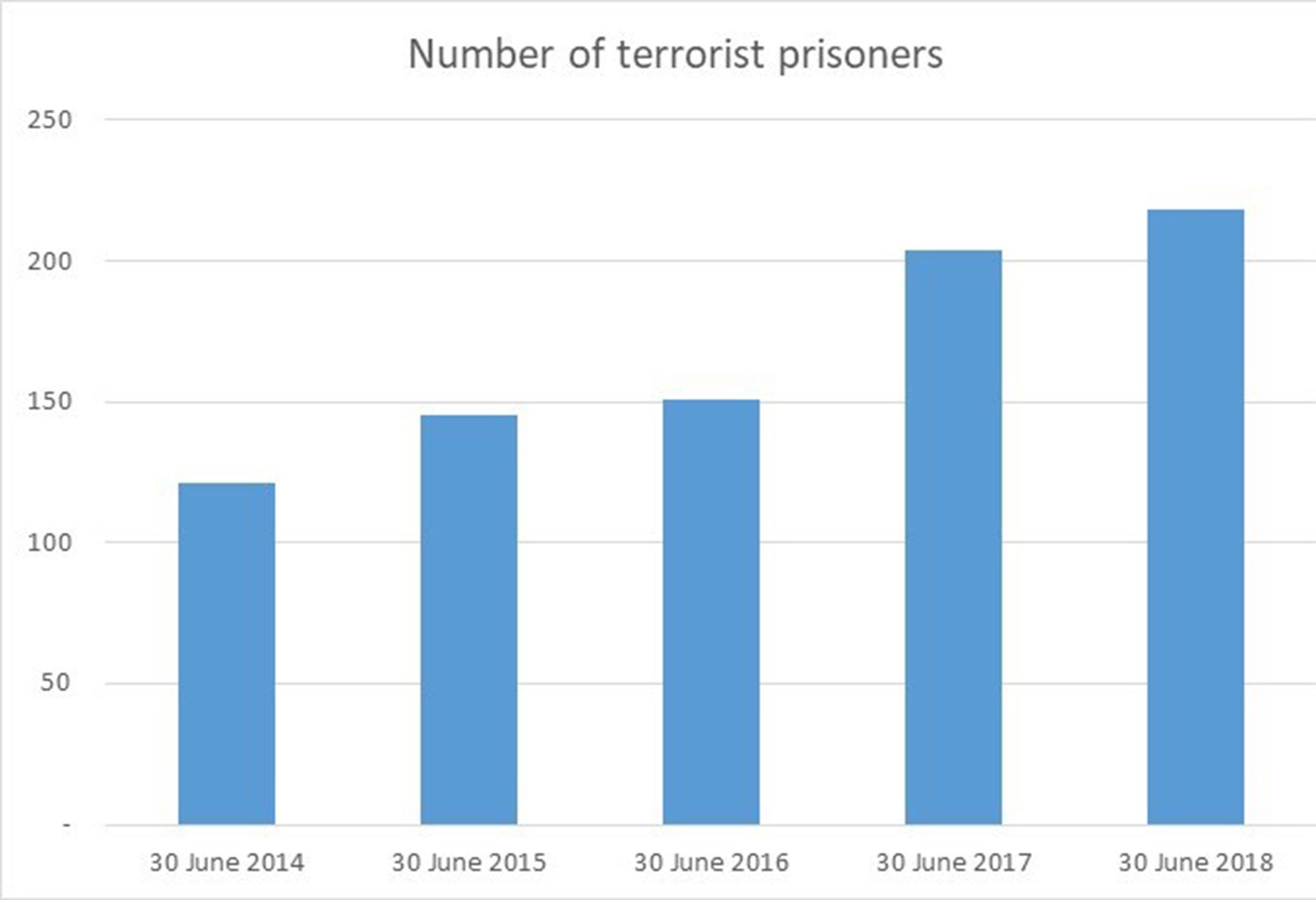

Amid the chaos, a record number of people are convicted of terror offences and proposed new laws would see even more jailed.

There are 228 people currently in prison for terror-related offences – 82 per cent Islamist, 13 per cent far-right and 6 per cent “other”.

But the Ministry of Justice (MoJ) says it is managing a far larger number of prisoners – 700 – under a “counterterrorism specialist case management process”.

A prison officer working in the high-security estate told The Independent that the figure “doesn’t come anywhere near” the real number of Islamist extremists inside.

“I’d put another zero on that and then some,” he added. “The extremists have their own foot soldiers radicalising people who are in for minor offences.

“You’ve got someone who is in for five or six years, an ordinary criminal, and all of a sudden they are radicalised into hating anything about the west.”

The officer, who spoke on condition of anonymity, is one of several sources who say the phenomenon of inmates claiming to convert to Islam inside prison and joining Muslim gangs is widespread.

He has noticed “no change” since a joint HMPPS and Home Office extremism unit was created in April 2017, and dismissed specialist training as a “laughable” box-ticking exercise.

Officials claimed staff would be able to “identify, report and challenge extremist views and take action”, but the officer said his colleagues were too few and too stretched to implement the policies.

“The problem is too big,” he added. “There is no time in an ordinary prison officers’ day to rehabilitate anyone. Nobody comes in to check whether these things are being done.”

Mr Acheson said it was “ludicrous” to expect prison officers to challenge extremists while they are struggling to maintain control.

“Any engagement is a long-term affair,” he added. “You can’t switch people on and off.”

Adam Deen, a former member of Anjem Choudary’s al-Muhajiroun terrorist network who now works to counter extremism, raised concerns that prisoners could merely jump hoops to be judged safe for parole.

“Any criminal wants to get out of prison early and it’s no different with Islamist extremists, they will say anything,” he added.

“We don’t know if someone is reformed. We can only know from their actions and then it might be too late.”

Mr Deen, the executive director of think tank Quilliam, said committed extremists could launch a terror attack “any time”, even years after their release.

“We should be concerned that so many of them are coming out, I don’t think the majority will be deradicalised,” he said. “Perhaps they will go quiet but I don’t think they will abandon their views.

“They should all be under surveillance but that’s going to happen so it’s a very vulnerable position for the country to be in.”

Choudary, whose Islamist network was linked to a string of terror plots, is due to be released imminently, the most notorious terrorist prisoner to be so.

The radical preacher is likely to be under heavy surveillance after serving over two years for inviting support for Isis, but experts are equally worried about lower-profile extremists who may not be so closely watched.

Police are already running a record 650 live terror investigations into the “most dangerous individuals” and the security services admit they do not have the resources to monitor the growing pool of 20,000 people who have appeared on their radar in the past.

The Westminster attacker Khalid Masood – who converted to Islam while imprisoned for a violent attack – was among their number and considered only a “peripheral” figure before his atrocity.

MI5 had investigated the Manchester bomber Salman Abedi but misinterpreted intelligence that could have prevented the attack, and spies were not aware of the London Bridge plot despite putting ringleader Khuram Butt under surveillance for attack-planning.

An intelligence review found the operation was suspended last March “due to resourcing constraints brought on by a large number of higher-priority investigations”, and Butt’s risk level was downgraded.

With 13 Islamist plots and four from the extreme right foiled since March 2017, several attack-planners have been jailed for life and put in separation units to stop them influencing fellow prisoners.

But a larger number of extremists have been convicted of lower-level terror offences, including spreading Isis propaganda and sending money to foreign fighters since the group formed in 2014.

The vast majority of terror offenders will serve a maximum of only five years and, of the 312 freed since 2014, 171 (55 per cent) had been sentenced to terms of less than four years.

Short prison terms have been linked to reoffending across all crimes, and several terrorists have already reoffended.

One, a former London council worker, was jailed twice within five years for disseminating terrorist publications.

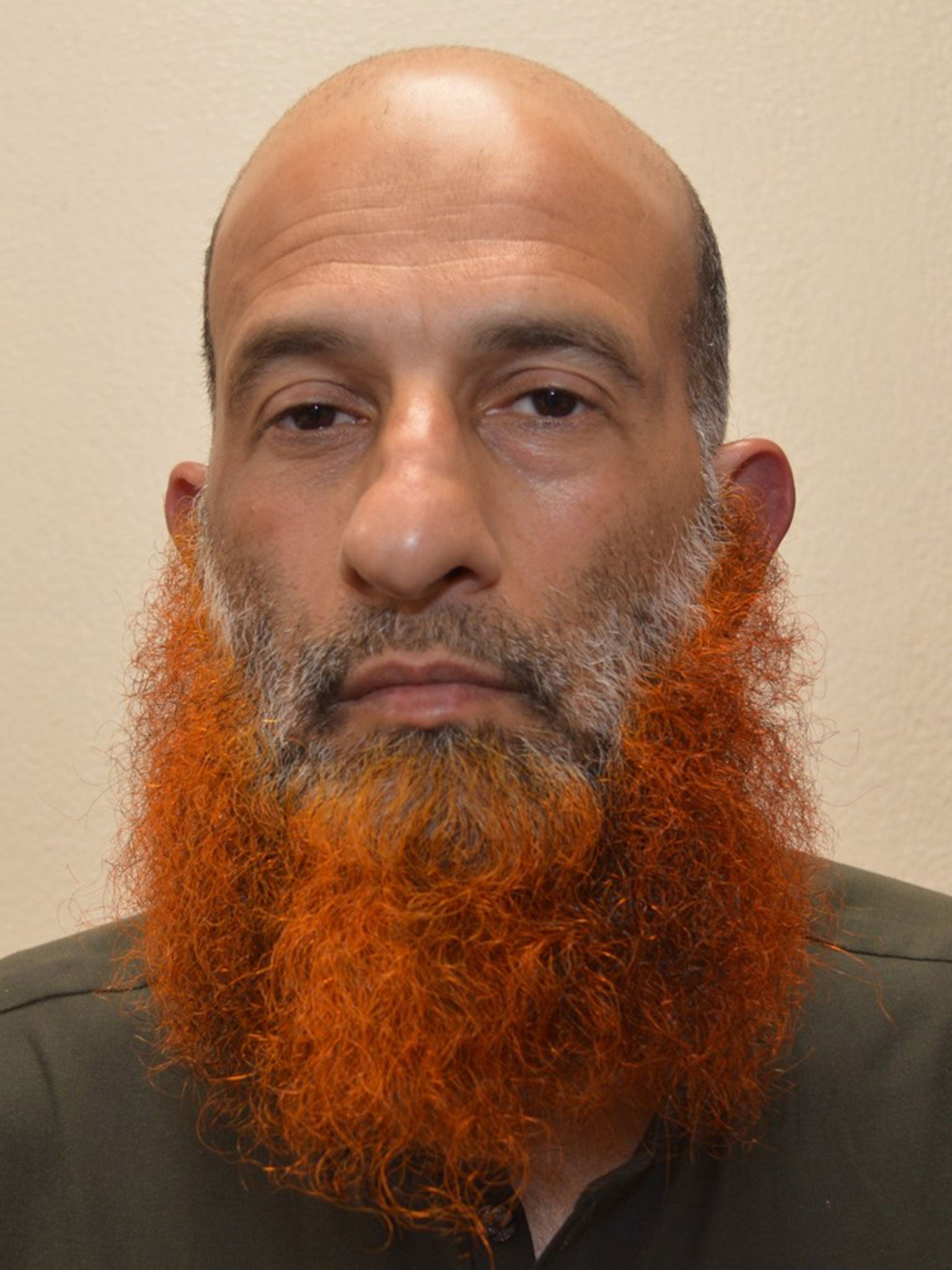

Khalid Baqa’s first sentence apparently did little to change his views, as he resumed spreading jihadi CDs and leaflets and was jailed again in July.

Mr Acheson said he does not believe authorities have the capacity to monitor terrorists or reintegrate them into society.

“We have no clear idea what impact long-term custody will have on the ideological commitment of these people,” he added. “Lax supervision risks a dangerous offender slipping through the net.”

Those released are monitored by the National Probation Service in coordination with police, who can use multi-agency public protection arrangements or licence conditions to limit their activity.

The government’s Contest strategy includes a desistance and disengagement programme that aims to rehabilitate terrorists with mentoring and psychological support as well as theological and ideological advice.

The Home Office is also establishing a series of experimental multi-agency pilots testing different models to better understand the risk posed by people previously judged a threat.

A prison service spokesperson said: “We are doing more than ever to counter the spread of extremist ideology in our prisons. This includes opening two separation units to hold extremist prisoners and training more than 17,000 staff to deal with extremist behaviour.

“We also recognise the need for stability, which is why we are investing £40m to improve the prison estate and tackle the drugs problem which is fuelling much of the violence, as well as recruiting 3,500 new officers.”