Send in the peacemakers: an answer to gang violence?

Police in London and elsewhere have been offering mediation services to help criminal gangs sort out their disputes without recourse to killing. It’s a controversial approach – but, reports Paul Peachey, the initiative has so far proved startlingly successful

The identified target has been named as a suspect in a kidnapping and torture that left the victim branded with a hot iron. Beyond that, the details of the episode are scant and the motive for the attack is unknown.

No one was there when police raided the house where the victim was supposed to have been held. And nobody is now talking, least of all the supposed victim, who has been seen hobbling around on crutches after he was chased down by a car in a second apparent “warning” that he was lucky to survive.

These are the few facts of the case mulled by two civilian mediators as they prepare to knock on the door of the alleged perpetrator to try to find out what has been going on. Armed only with a “voice and a badge”, it’s their job to approach some of the country’s most dangerous men to try to persuade them to end their conflicts and to prevent anyone from dying.

Damion Roberts, himself a former high-ranking gang member, and Donovan Housen, a youth worker and band manager, are both members of a company contracted by the Metropolitan Police with the task of trying to defuse hundreds of disputes between young gang members and their associates. Police say the little-known tactic has contributed to the decline in gang violence in the capital.

The civilians move in when the police can go no further and seek to win the gang member’s trust with the promise that nothing will go back to police unless there is a threat to life or public disorder.

Over 18 months of following some of the mediators, a joint investigation by The Independent and BBC 5 live has seen mediators attempt to organise a monthly debt repayment plan to settle a murderous dispute, and set up round-table meetings between teenagers suspected of stabbing each other in an escalating pattern of tit-for-tat violence.

The address that the two men have been given for their current case is part of a new low-rise block on a south London estate. They employ the first rule of mediation: after the knock on the door, move to the left or to the right – never stand in front of the door. It’s a rule borne of bitter experience from Roberts’s own gangland days when a gun was shoved through the letterbox of his own home and shots fired that only just went over his head.

They guess correctly that the subject is at home as he’s on probation tag with curfew conditions. At first he is wary of the mediators who tell him they are there to “keep the peace without getting the police involved,” before he lets them in. Then he steadfastly denies that he had anything to do with the kidnap plot.

“The first time I’ve heard of a kidnapping was when you lot told me today,” he says at the conclusion of a 45-minute conversation in the hallway of the flat. “I haven’t got a beef with nobody… people always seem to have a beef with me. I’ve been stabbed three times and shot twice… but I’m not part of that any more.”

For the past five years, mediation has been used by Scotland Yard to try to prevent gang disputes from ending in violence. First used in the United States, it was employed as part of a trust-building exercise during the Northern Ireland peace process.

Police in the West Midlands adopted the idea after two innocent young women were killed during a violent dispute between rival gangs in January 2003. It has since been taken on by the Metropolitan Police, which faces a widespread and diverse gang problem with a current estimated 3,500 gang members from around 225 different groups.

The force has poured resources into tackling the problem and has seen big falls in knife and gun crime and teenage murders from 29 in 2008 to 12 last year.

Mediation is used when enforcement is ineffective and the consequences of the feud are likely to be seen in spiralling tit-for-tat crimes based on business disputes, petty rivalries or issues over respect.

“Their job is to stop violence,” said Andy Simon, a former detective and the chief executive of the mediation service Capital Conflict Management (CCM). “I tell them that mediation is about having the very difficult conversation that those individuals can’t have themselves.”

Feuding gang members are often approached when they are at their most vulnerable – in hospital from stab or gun wounds. Half of the victims who survive shootings are unwilling to help the police, according to the force’s own figures. But while they’re confined to bed, it is viewed as an opportunity for the civilians to resolve the crisis and take them out of the gang lifestyle.

The mediators are often told that they should allow the gangs to get on with it. Simon points to Home Office figures putting the cost of a murder to society at £1.7m from health and police costs.

“It’s something that affects our community and we shut our door to it on a daily basis. It makes us change our lives instead of living it normally,” he said. “If someone comes to your street, your town, your shopping centre and stabs and shoots somebody, the next time you think about going to that place you’ll think twice.”

The response in London is a team of some 30 mediators – including entrepreneurs, former gang members and youth workers – picked and trained for the task to tackle conflicts that range from playground name-calling that has escalated to a stabbing, to serious organised gang violence.

For the tactic to be successful, it needs both sides in the dispute to come together and the process is a laborious one that can take months to reach a face-to-face meeting between the feuding parties and a written non-aggression pact.

It only works for a select group of cases. One man at the centre of a tit-for-tat murders between postcode gang rivals refused to speak with mediators. Although he left London, he became involved in a fresh gangland feud in another city that left a third man dead and a teenager serving a life sentence for murder.

In another case, a young man freshly out of prison agreed to meet mediators but not the man who stabbed him outside a probation office “because there’ll be a fight”. Another, visited in prison and deeply embroiled in the gang lifestyle, said that there was no point in dealing with the mediators because he would not live until he was 25, said John Mackenzie, the former operations director of the mediation company.

But at least three people whose lives were at risk have survived after an intervention by the mediators, according to an 2013 report, amounting to more than £5m saved.

Mediation, however, has been criticised by an US academic whose work has inspired other anti-gang measures in Britain. “The issue with gang mediation is that it confers on two parties [a] standing that they should not have,” said Professor David Kennedy, director of the US National Network for Safe Communities.

“We don’t want to look at their violence and say to them: we understand why you do this and we respect your reasoning enough to engage with your thoughts and ideals and actions in the hope that you will change your behaviour. That’s fundamentally wrong.”

Scotland Yard defended the tactic as part of the armoury of enforcement and gang-diversion tactics being used to tackle the problem. “Mediation is something that benefits and suppresses violence very quickly,” said Det-Chief Insp Tim Champion, of Scotland Yard’s anti-gang crime taskforce Trident. “If the violence is reduced then that’s a step in the right direction.”

Mediators have only once been pulled off the job because of a threat to their lives. Usually they are welcomed as a way of getting rid of an unwanted threat. But they always work in pairs given the potential danger of their work.

Roberts – who often works with Housen – is a former senior member of the London Fields gang and ran drug dealing rackets in Essex after joining a gang at the age of 13. He carries the scars of drug rivalries including slashes on his hand after a “gentleman with a machete tried to chop off my head”.

His life changed after the second of two spells in prison, when nobody visited him apart from his family. Gang members often reported that mediators were often the only ones to see them behind bars. Now 33, Roberts works as a mediator and has set up a company to get young unemployed people back into work.

After weeks of shuttle visits and closed doors, Roberts and Housen learn that there is more to the story of the man branded with the iron. It was thought to be linked to the loss of thousands of pounds of drugs by the victim given to him by members of a street gang. The man – who was thought to still be selling drugs on the street – finally agrees to meet in a branch of Nando’s after he accepts that the mediators are not undercover detectives. The mediators want to get him into employment, stop him selling drugs and set up some sort of repayment in instalments to lift the threat from his life, if the gang accepts the idea.

Alternatively, they consider a move out of the area under a Scotland Yard protection scheme – but the person has to be willing to co-operate with the police and he shows little intention of doing so. But before the case can go much further, the victim is arrested for selling drugs on the street and the mediation is brought to a close.

“Some people will say the right thing is to call the police... but he would not co-operate,” said Housen. “What they don’t want is to be seen as grass or snitch. If they talked to police, they would have to live in that community and put themselves at risk. That’s a death sentence. When they speak to us, it’s confidential. Some of them are not forthcoming. They want to take it to the street and hoping the issue will go away – and it doesn’t.”

The repayment scheme, however, has worked before, according to officials. A repayment plan was set up between a 15-year-old boy and a dealer following a dramatic fallout over the proceeds of drug sales, said Mackenzie, a former Scotland Yard detective before he joined CCM.

The crisis escalated after the teenager was called to a meeting with the dealer, who pulled out a gun to try to shoot him. But the teenager pulled out a knife and stabbed him first. The dealer survived but put a contract out on the boy.

At some point if nothing is done, eventually this 15-year-old is going to lose his life,” said Mr Mackenzie. “It was fairly clear that the 15-year-old wanted the problem to go away, the drug dealer just wanted his money. We were able to put the two together and they came up with a payment plan.

“I know it sounds absurd, and morally some people may think that’s just not right. But that 15-year-old is still alive, he’s moved on and has got his life ahead of him.

“That’s what we’re about – trying to find a way of saving people’s lives. We’re not setting up repayment plans for everybody that owes a drug dealer money. But that was one instance where a young person was undoubtedly going to lose their life so that’s what we did.”

Turning point: Two innocent victims

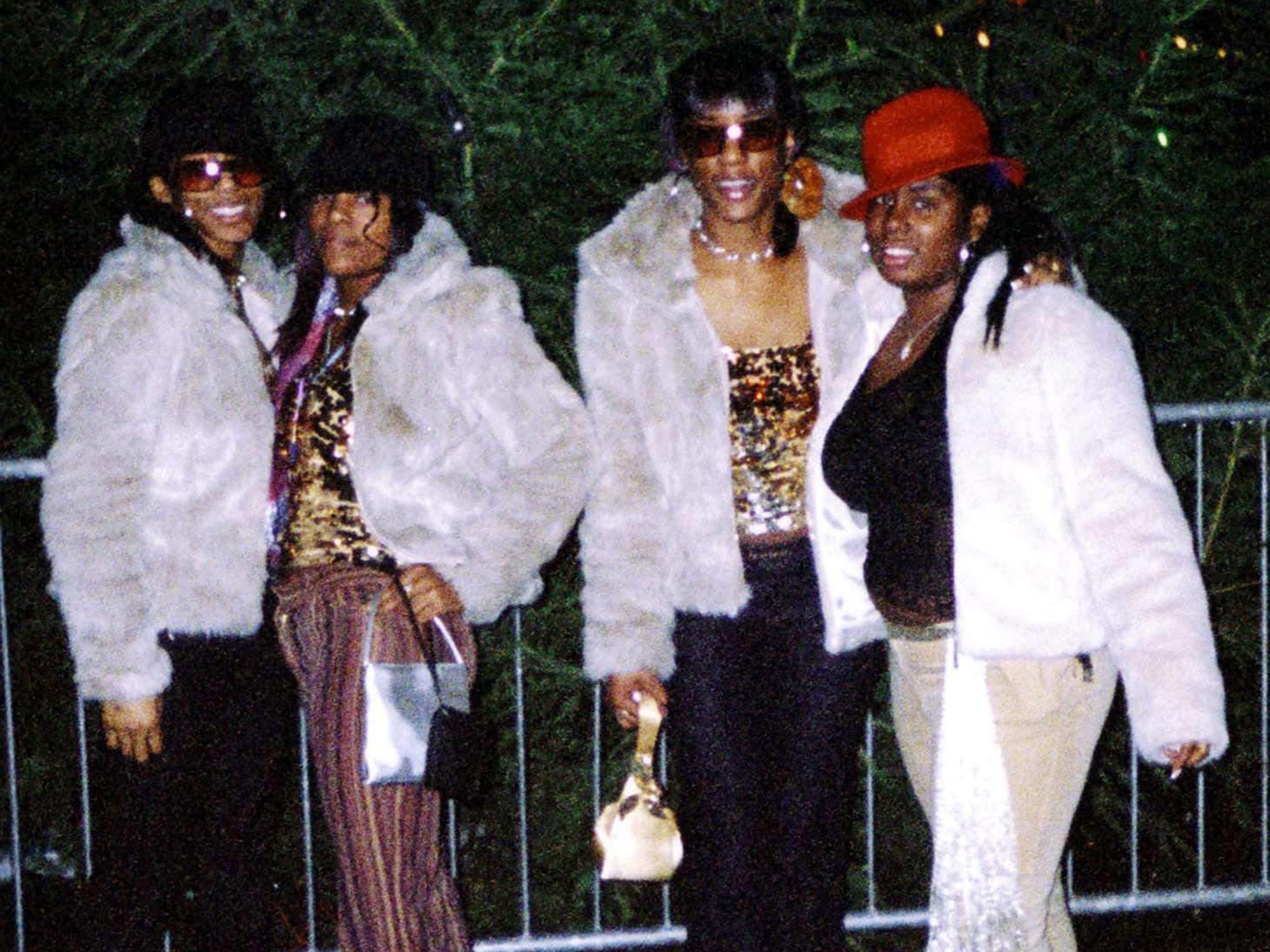

The murders of teenagers Letisha Shakespeare and Charlene Ellis in Birmingham in 2003 changed the way that gang violence was addressed in Britain.

The two young women were innocent bystanders when they were shot dead during a turf war between two rival gangs, the Burger Bar Boys and the Johnson Crew. The killings brought into public view the struggle between the two gangs over drug markets after a decade of shootings and violence between the rival groups.

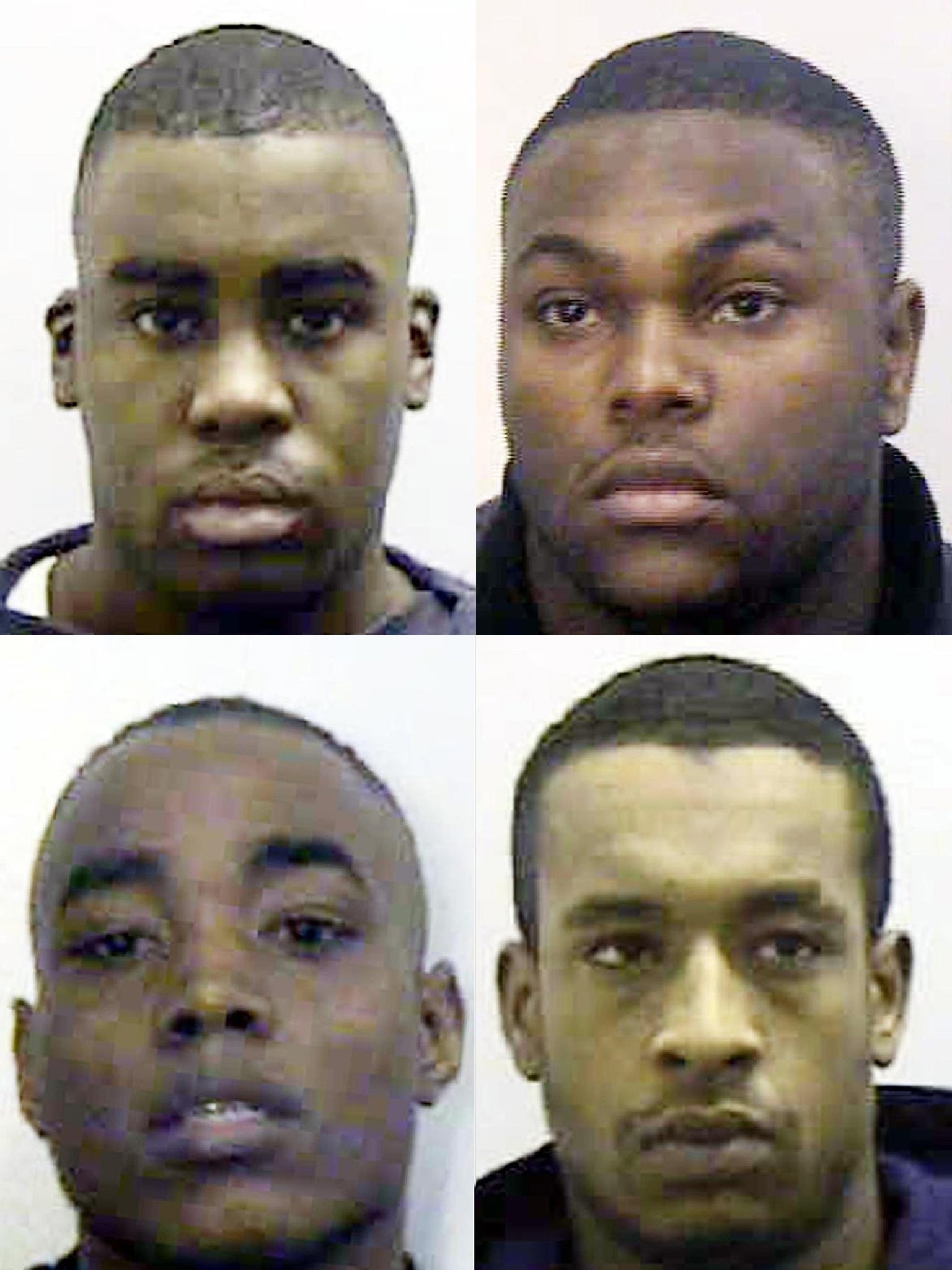

There were six shootings every day in Birmingham by the time that a gang member opened fire on a crowd of revellers with a machine gun – leaving the cousins dead and four others injured – in a botched revenge attack. Four men were later convicted of murder and jailed for life.

The killings put pressure on police and politicians to change the way they dealt with gang crime, and led to the establishment of the mediation service, a process that had already been under way at the time of the murders.

The parents of the victims have worked since their daughters’ deaths to campaign against gang violence.

On the tenth anniversary of the killings, Beverley Thomas, the mother of Charlene, said: “My message to youngsters is to think about the impact it has on families, the community, and how it affects people closest to the victims. Burying your child is something you never expect to have to do as a parent. You expect your children to bury you.”

The mediation model was later taken to London and adapted for the much more diverse gang population with many more members

Research has shown that the average age for a first offence to be committed by a gang member is 15, with half of all shootings and nearly a quarter of serious violence gang-linked.

Gangland Mediators will be broadcastat 9pm on Sunday on BBC 5 live