Thousands serving community sentences 'have undetected mental health problems'

Exclusive: Fears for thousands of people trying to cope with mental health conditions without support after being through criminal justice system

More than 10,000 criminals serving community sentences are likely to be suffering from undetected mental health problems, increasing their risk of self-harm, suicide and reoffending, according to analysis by The Independent.

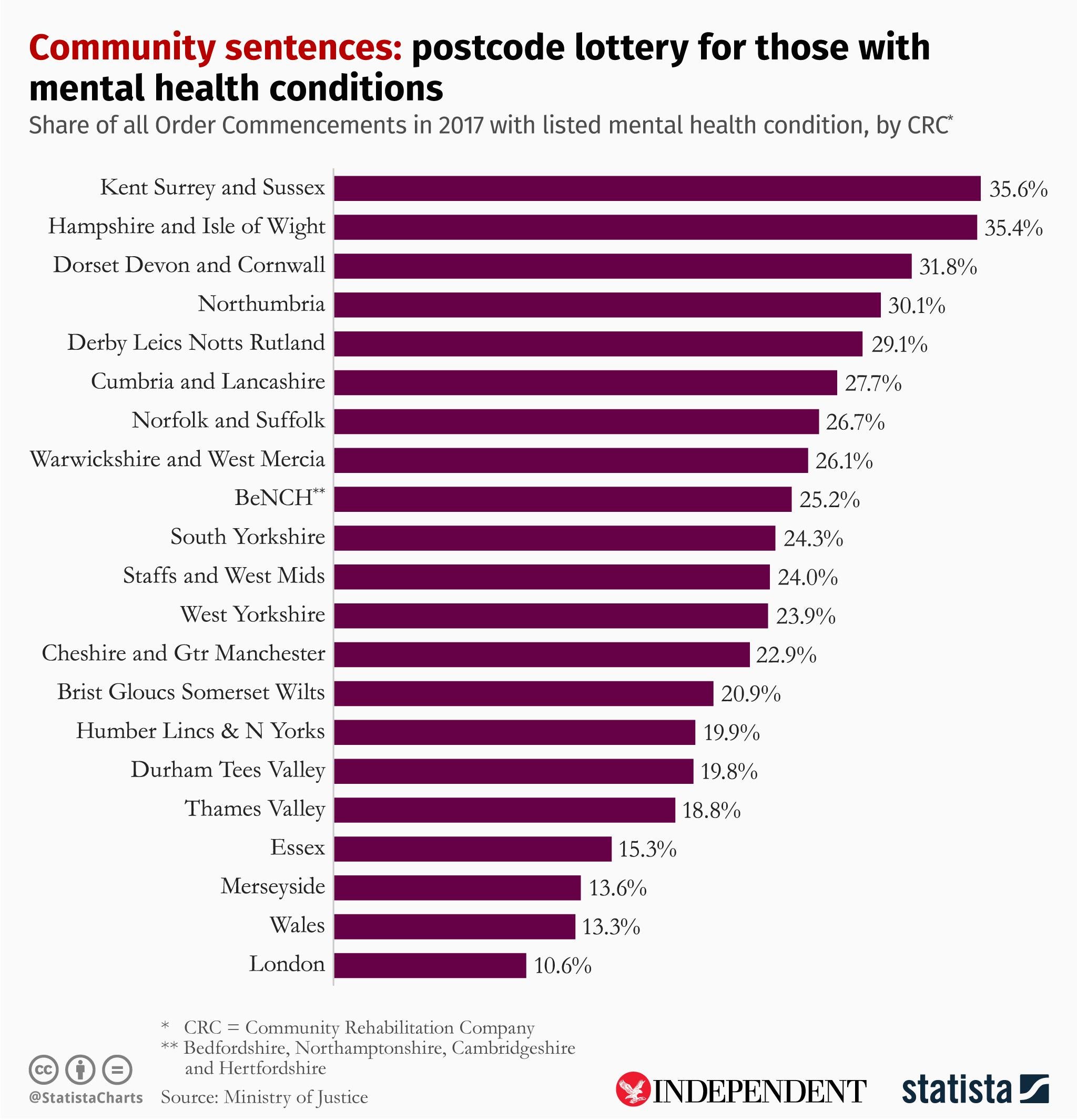

Figures obtained via freedom of information requests reveal the identification of such conditions among people serving non-custodial terms varies wildly across the country, but in almost all areas falls short of the government’s own assessment of their frequency.

Some 91,293 people are serving community sentences in England and Wales, and the government estimated in July last year that 35 per cent were suffering from a mental health condition.

However, the rate of people self-reporting a mental health need on starting a community order ranged from 10.6 per cent in London to 35.6 per cent in Kent, Surrey and Sussex, according to data obtained from the Ministry of Justice by charity Revolving Doors Agency and shared exclusively with The Independent.

If the government’s own assessment of the prevalence of mental conditions is correct, that would indicate there are nearly 4,000 people serving the orders in London alone who are likely to be suffering from a mental illness, but have not reported it.

Nationally, the detection rate averages out at 23.57 per cent. That indicates a total discrepancy of some 10,435 people whose conditions are undiagnosed – and are therefore trying to cope without the support they may need to stop them harming themselves or others.

Lord Keith Bradley, author of a landmark report on people with mental health problems in the criminal justice system, said the MoJ figures highlighted a fundamental problem in supporting offenders in the community with mental health-related disabilities and complex needs.

“The data suggests that the level of information being shared with the CRCs is not robust enough,” he told The Independent.

“There’s an inadequacy in screening problems to properly identify all those with mental health conditions and where that information is collected, it’s not effectively shared along the criminal justice pathway to ensure that at each point there is the most knowledge of the needs of the individual so that interventions are appropriate to those needs.”

Lord Bradley also suggested the lack of appropriate care could contribute to high levels of reoffending – more than a third (34.1 per cent) of adults reoffend after starting an order.

“People in the community are not properly connected to the support services they need to ensure the problems they’ve encountered, which may have led them into the criminal justice system in the first place, are addressed,” he said.

The data comes as self-inflicted deaths are revealed to be the leading cause of death among people serving community sentences, accounting for almost a third (31.1%) in 2017-18. Those on community orders are also more than 10 times as likely to die by suicide than the general population.

Rory Stewart, the prisons minister, lauded community orders over custodial sentences for crimes including burglaries and shoplifting when he spoke last week about the possible scrapping of jail sentences of six months or less.

“In my responsibility to protect the public, the public are safer if we have a good community sentence rather than putting people in prison for short sentences and it will also relieve a lot of pressure on these prisons,“ he told The Daily Telegraph.

David Gauke, the justice secretary, suggested greater use of community sentences when he axed plans for new prisons for women in June 2018.

He also announced plans to improve access to mental health support for offenders in the community in August 2018 following an MoJ study that highlighted very low use of treatment requirements as part of community sentences. Five pilot sites were launched to trial mental health referrals for vulnerable offenders in the community.

Less than 1 per cent of community sentences handed down since 2010 included a mental health treatment requirement, and their use halved between 2012-13 and 2017-18, falling from 0.6 per cent to 0.3 per cent.

Legal thinktank the Centre for Justice Innovation urged the MoJ in December 2018 to urgently reconsider the level of funding available for drug and mental health treatment for offenders in the community, and reconsider whether the funding should be ring fenced.

Phil Bowen, director of the Centre for Justice Innovation, said: “Effective community sentences cut reoffending and cut crime. But for the public and the courts to have confidence in them, it is vital that health and justice services are brought together to divert people with serious mental health conditions from short custodial sentences through improved access to treatment.”

Charlotte Douglas*, 54, has a personality disorder and depression and is serving a community sentence in London. She is a repeat offender, having served custodial sentences and feels support has been inadequate.

“I should had have trauma therapy, that is what I know now nine years later,” she said. “There was no diagnosis, no care plan.

“When you tell them [offender managers] about emotional problems they give you the number for Samaritans and a crisis line.

You feel disappointed and rejected. Without support you can have more problems and can get in more trouble. It’s a catch 22. I’ve been crying for help for a long time and it shows.”

Professor Charlie Brooker, honorary professor of criminal justice and mental health at Royal Holloway and one of the authors of an investigation into the prevalence of mental health disorders in the probation population, said improved mental health training for offender managers was needed to sufficiently support those on community sentences.

“In a two-year training programme, a day and a half was spent on mental health,” he told The Independent. “That is not anywhere near enough to be able to assess with any confidence someone’s mental health status.”

Christina Marriott, chief executive of Revolving Doors Agency, said questions need to be asked about whether “CRCs understand the mental health needs of people serving community sentences, why they are failing in this first step of identification and what actions they are now taking”.

“For the community sentences to work, CRCs must be able to identify mental health need,” she said.

“This is the first step to people getting the healthcare they need. And this care can not only help people to stop reoffending, it can save lives – people on community sentences have a suicide rate of 10 times that of the general population.”

A Ministry of Justice spokesperson said: “As with other members of the public, the mental health of those serving community sentences is assessed and treated by trained medical professionals, not their supervising probation officer.

“Community Rehabilitation Companies work closely with healthcare partners to ensure offenders receive the support they require.

“We are also piloting a pioneering scheme that sees offenders in five areas diverted towards treatment for mental health and substance misuse issues to tackle the root cause of their reoffending.”