More than 80 per cent of female inmates locked up for non-violent offences, new figures show

Exclusive: The figures come amid a drive to clear jails of women who pose no danger to the public

More than 80 per cent of female prisoners have been locked up for non-violent offences such as shoplifting, new figures show, as a drive is launched to clear jails of women who pose no danger to the public.

At least 17,000 children are separated from their mothers every year because of the “devastating impact” of imprisonment and are more likely to suffer homelessness, family problems and trouble at school, the Prison Reform Trust (PRT) warned.

Arguing that women are treated more harshly than men by the criminal justice system, it announced it had secured a £1.2m lottery grant to mount a three-year campaign to cut the number of female inmates.

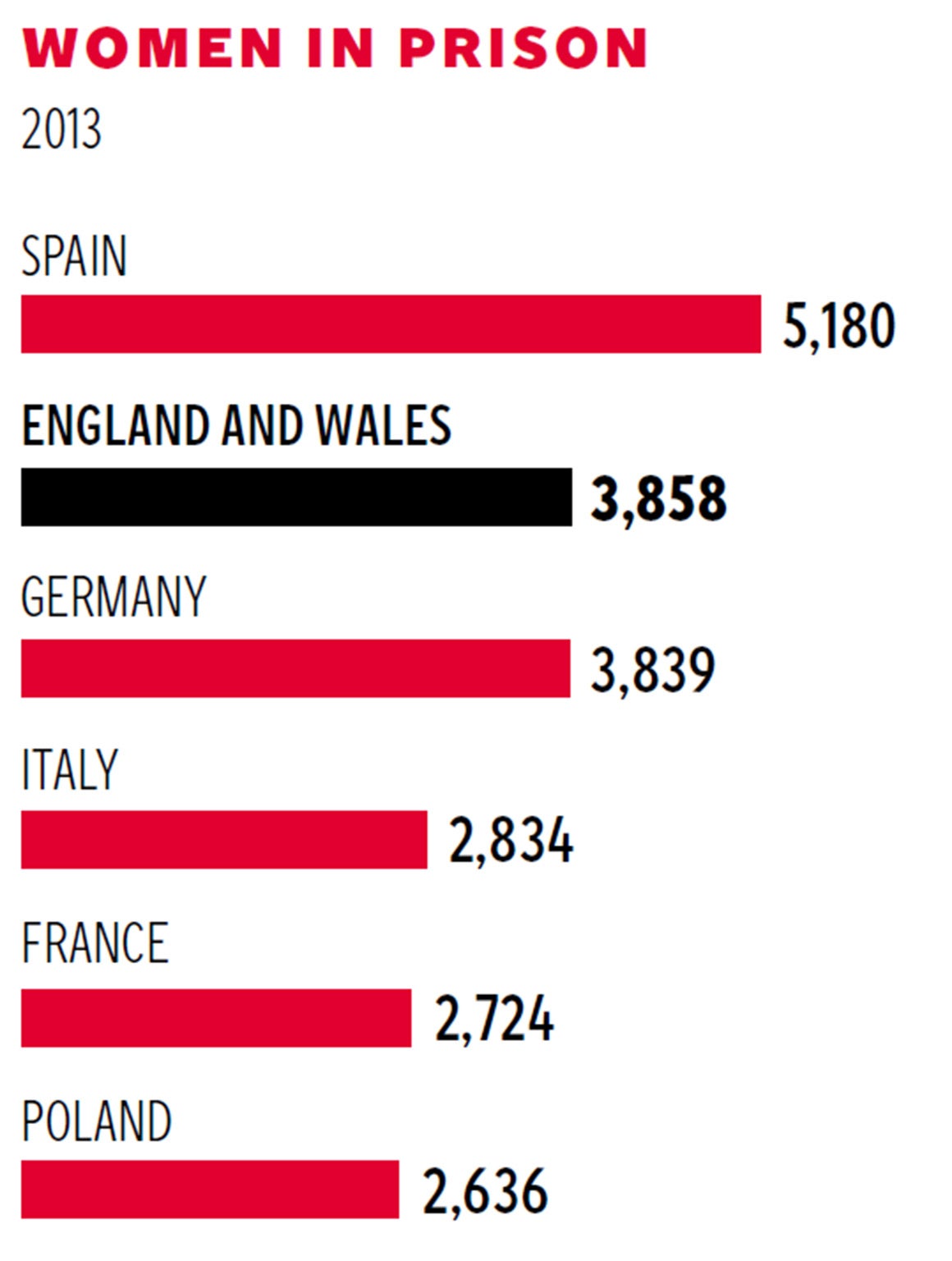

About 4,230 women are currently serving sentences in UK prisons, including around 3,890 in England and Wales, 300 in Scotland and 40 in Northern Ireland. The numbers have fallen slightly in recent years, but are still twice as high as 20 years ago.

Penal reformers have drawn encouragement from a recent commitment from the Ministry of Justice to reduce the number of women in prison.

However, the continuing disparity between the background of male and female prisoners and the offences for which they are jailed is underlined by fresh research published by the PRT.

It found that 81 per cent of women are being imprisoned for non-violent offences, including shoplifting and handling stolen goods, compared with 70 per cent of men. As a result they are disproportionately more likely to be jailed for less than 12 months, the sentence with the highest reoffending rate.

More than half (53 per cent) of female prisoners reported suffering sexual, physical or emotional abuse as a child, against 27 per cent of male inmates. They are nearly twice as likely to suffer depression, and account for 26 per cent of self-harm incidents in England and Wales despite only representing 5 per cent of the prison population.

The PRT said three-fifths of female inmates have dependent children and one-fifth are single mothers. Very few youngsters whose mothers are locked up are cared for by their father, whereas most children with a jailed father remain with their mother.

Its campaign will focus on areas of the UK where large numbers of women are jailed in an effort to identify alternatives to prison. It will urge courts to consider the greater use of non-custodial sentences for female offenders and press for better mental health services and social care for vulnerable women.

A Ministry of Justice spokeswoman said: “Crime is falling and fewer women are entering the justice system. We want to see even fewer women offending but they need the right support to break away from crime. Our reforms will mean for the first time virtually all female offenders will be supported to address their complex needs in prison and on release.”

Jenny Earle, the director of the trust’s programme to reduce women’s imprisonment, said: “We need to listen to women with experience of the justice system and take seriously the mounting evidence that short periods of imprisonment are particularly destructive for women and the families who rely on them.”

Dawn Austwick, the chief executive of the Big Lottery Fund, said: “This project builds on a strong body of evidence, looking at interventions to help women at risk of offending address underlying issues and improve their lives.”

Nancy Loucks, the chief executive of the charity Families Outside, said: “The impact on children when a family member goes to prison is significant and enduring, particularly when a mum goes to prison. Their housing may be at risk, their schooling may suffer, their care arrangements may mean they’re separated from siblings and other family. Up to a third develop serious mental health issues, and they are at higher risk of offending themselves in later life.”

Case study: ‘A tenuous grip on family life was made ever more precarious by my imprisonment’

I am a mother of two and I had a profession. I had never been in any kind of trouble before. I was put into an untenable financial position and I was at risk of losing everything. I tried to put it right through legitimate measures which, it transpired, made the situation worse. I stole from my employers in desperation and mental turmoil and life has not, nor ever will be, the same again.

This was my first and only offence. I confessed, repaid the money, and had lost the family home and my career. Most importantly, I was the sole carer of my children. Despite this, I was sent to prison. The long waiting time between arrest and sentencing was the worst kind of purgatory, a surreal and tortuous period not lightened by reassurances from the police, probation and legal advisers that I would not get a prison sentence. When the verdict was announced, despite being terrified for my children, it was a relief. I could get through prison, fully pay for what I’d done and emerge to rebuild my life. This wasn’t to be the case.

My children narrowly missed being put into care. A tenuous grip on family life was made ever more precarious by my imprisonment. This was only compounded following my release. I had started feeling nothing but remorse and shame, this was now heavily overlaid by anger. The prison sentence didn’t make sense – I don’t know what was achieved by it and it seemed to me to be vindictive and pointless in the extreme. I wasn’t expecting to get away with anything, but at the same time I didn’t expect to be kicked while I was already well and truly down.

It took six months from my release from prison to find paid work. I still cannot get insurance and it’s a struggle every month to make ends meet. I try to tell myself that I can come out of this one day, but it is a long game and requires extreme levels of tenacity, patience and mental fortitude. In reality, I don’t expect to outlive the consequences of my conviction, nor its impact on my children.