Molly is a teenage girl who likes Hannah Montana, Lily Allen and Pink (or so the covert investigator who plays her would like internet paedophiles to think)

Mark Hughes goes undercover with the Metropolitan Police child sex unit

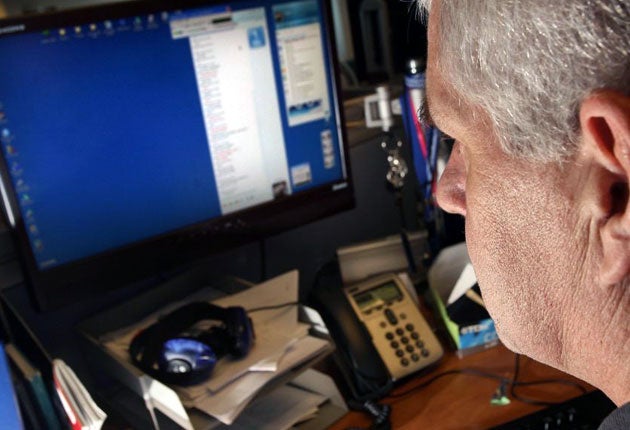

For a middle-aged man, Jonathan Taylor's music and television tastes could be described as peculiar. He spends his spare time watching Hannah Montana and listening to Lily Allen and Pink. For this sacrifice, his three young daughters think him a wonderful father. But, rather like Montana, Mr Taylor is living a double life.

At work he becomes a young girl called Molly, an online pseudonym he has created in his bid to lure internet predators who are looking to engage children in conversations about sex. He does it because he is a police officer working as a covert internet investigator for the Metropolitan Police's paedophile unit.

"My job is basically to pretend to be a young girl, go online and catch paedophiles," he says. "Social networking sites are the new park and playground. The days of the paedophile hanging around these areas have not gone, but there is no need for them to take such risks, because they can go online and take their pick."

The link between the internet and paedophilia was highlighted in a disturbing case earlier this month. Vanessa George, a nursery worker in Plymouth, admitted taking indecent pictures of children in her care and sharing them online with fellow paedophiles Colin Blanchard, of Littleborough, Lancahsire, and Angela Allen, from Nottingham.

It is the prospect of uncovering abuse networks such as these that motivates Mr Taylor and his colleagues. But the work required to dupe internet child abusers is detailed and painstaking.

"I have to think like a 14-year-old girl," he explains. "I even have to know about bra sizes. I need to write in 'text speak'. The way we operate, paedophiles will not be able to tell the difference.

"I have to create as close to a real person as is possible. So if my profile says I am living in Camden, north London, I go to Camden and I find out about the local area. The last thing we want is for an investigation to fall apart because I get caught out and make a mistake about where I am supposed to live."

There are, of course, legal restrictions surrounding what Mr Taylor can and cannot do while online. He must operate within a strict framework which says he is not allowed to be an agent provocateur – in other words he cannot incite people to commit crimes which they would not otherwise have committed. Yet the problem of children being targeted for sex remains, so the unit has to focus its efforts on the most serious offenders – those who indicate that they intend to molest children.

One such offender is Andrew, a 34-year-old man from Gloucester. After talking to "Molly" on the internet, he swaps details with "her" and they start exchanging messages. Mr Taylor explains that Andrew has indicated he wants to travel and meet Molly, but will be arrested if he does. As he speaks, Molly receives a message. It is from Andrew, but Mr Taylor refuses to reply immediately. "I can't," he writes. "I'm a young girl and I'm in school." Such time constraints mean the majority of the covert investigators' work is done after 3pm, when children are on their home computers after school.

For every Andrew there are thousands more sex offenders online. Research suggests that 0.3 per cent of the internet population are sex offenders, which equates to 125,000 of Britain's 42 million adult internet users. Last year, more than 14,000 reports of sexual abuse against children were made to police in the UK, but Mr Taylor says the true scale of the problem is unknown. He explains: "This is what is called a non-statistical crime. We do not know the true extent of it because not all of it gets reported. Why? Because children do not always report crimes of abuse. Sometimes they don't even realise a crime has been committed against them.

"People don't realise the scale of this problem. They read about high-profile paedophiles like Roy Whiting [who murdered Sarah Payne] or famous ones like Gary Glitter, but they don't realise that for every one of them there are hundreds more. And it's not just your stereotypical flasher in a mac; the people we arrest are from all walks of society. They are doctors, lawyers, teachers, businessmen and even policemen."

Should Andrew travel from Gloucester to meet Molly he will be arrested and interviewed. Much of the evidence in these types of cases is made up of internet conversations and any images or video footage. He will be given a chance to explain himself to officers.

But Detective Chief Inspector Graham Grant says that few of those arrested do explain their actions. "Most of the people we arrest say 'no comment' and then plead guilty when it goes to court due to the sheer amount of evidence we have against them," he said. "Of the ones that do speak it's always the same old stories. They claim they knew they were speaking to a police officer. Or they say they had only travelled to meet the child to save them, or to warn them of the dangers of speaking to people on the internet. It's nonsense and the obvious question is, 'If that is the case then why were you masturbating on the webcam?'."

Det Ch Insp Grant has worked in the paedophile unit for two years. Before that he investigated murders. Yet his final case in the homicide team before his transfer gave him an insight into the world of child abuse. He was the senior officer investigating in the murder of Peter Connelly ("Baby P").

He admits that, since joining the paedophile unit, the scale of the problem has shocked him. "The challenge for us is keeping up with them and finding out what websites they are using," he said. "The ones we have identified may be just the tip of the iceberg. That said, we are not trying to scaremonger. If parents simply watch which sites their children are going on and ensure they only talk to people who both the child and parents truly know, then they should not be at risk."

Det Ch Insp Grant adds: "Police must operate within the law and play a delicate balancing act. We have a duty to enable these people to live in communities once they are released. Experience shows that if they are outed then they will be at risk.

"We live in a democratic society and, whatever risk these people pose, our laws entitle them to safety. Re-offending is not a given and the key for us, as police, is to appropriately manage them and their risk to prevent re-offending."