The Krays: Why do people still admire the notorious East End gangsters who murdered their way to wealth?

London crime kingpins were arrested 50 years ago but their peculiar appeal endures

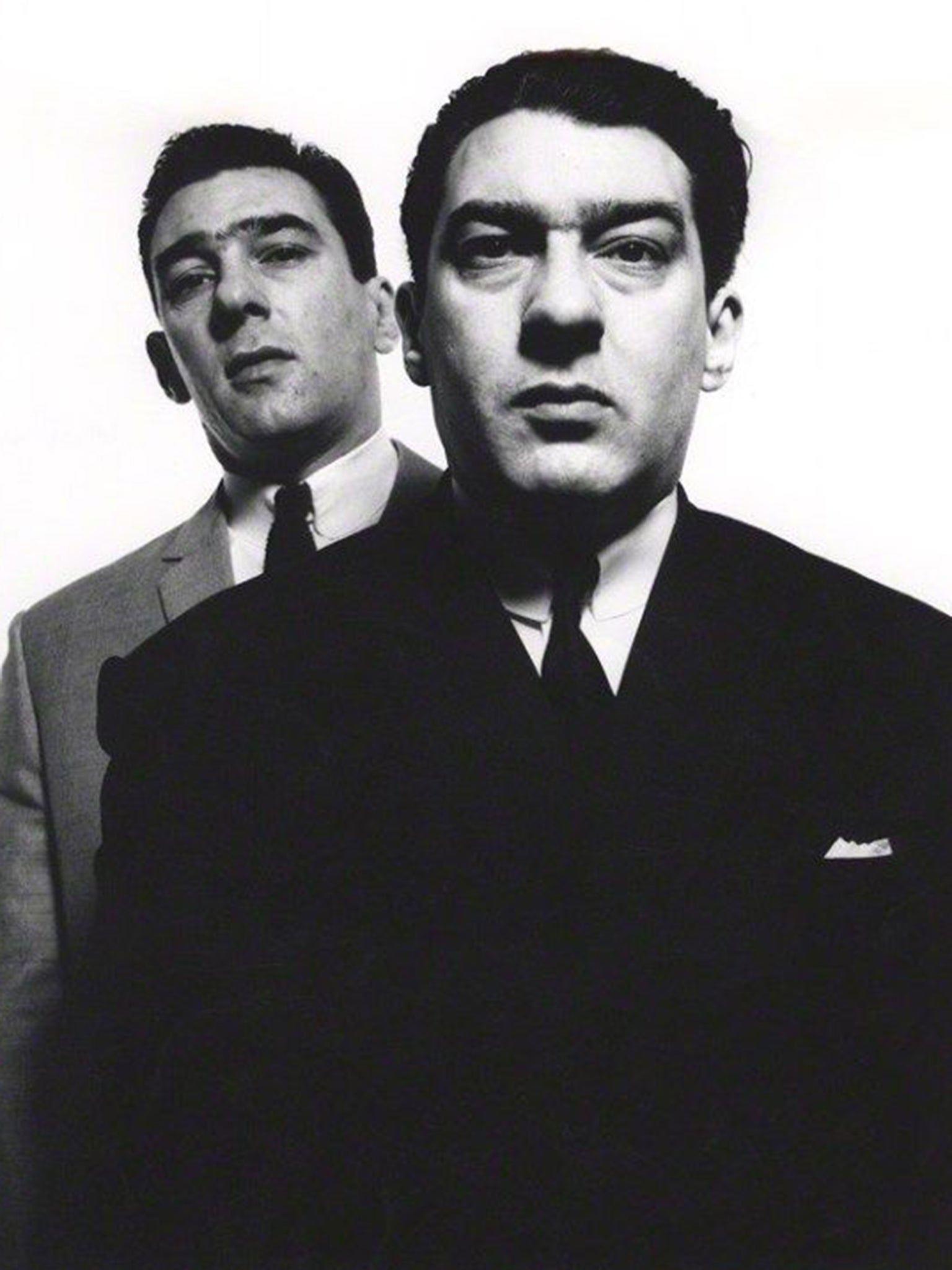

This week marks 50 years since the arrest of the notorious East End gangsters Reggie and Ronnie Kray.

The twins were deeply embedded within the post-war London underworld, and were kingpins of organised crime feared for their enforcement of protection rackets, armed robberies, arson attacks and murders, notably the famous dispatching of George Cornell and Jack “The Hat” McVitie.

They were also celebrities, Swinging Sixties nightclub owners who courted Hollywood stars like Judy Garland, Frank Sinatra and George Raft and British pin-ups such as Diana Dors and Barbara Windsor. They were even photographed by David Bailey. In Ronnie’s own words: “We were f***ing untouchable”.

This gangland Tweedledee and Tweedledum – who loved their dear old mum – were convicted for their crimes in 1969 and spent the rest of their lives in prison, Ronnie dying of a heart attack in Broadmoor in 1995, Reggie five years later of bladder cancer.

They have been played twice notably on film: by Spandau Ballet siblings Gary and Martin Kemp in The Krays (1990) and more recently by Tom Hardy, in both roles, in Legend (2015).

James Fox and Richard Burton meanwhile visited Ronnie in jail to press him for details ahead of their portrayals of loosely similar gangsters in Performance (1970) and Villain (1971) respectively.

Morrissey made them the subject of his 1989 single “The Last of the Famous International Playboys”, singing from the perspective of a starstruck criminal writing a letter of adulation to the brothers from his cell: “Reggie Kray do you know my name? Oh don’t say you don’t, please say you do...”

This last directly addresses one of the most troubling aspects of the Krays and their legacy: our habit of venerating these brutal men and our complicity in their myth-making.

Tours to their preferred boozer, The Blind Beggar in Whitechapel, continue to do a roaring trade and they have long since entered the folklore of the capital, a process they were only too happy to encourage.

Always image-conscious, the Krays understood the publicity value of paying for old ladies’ teas at Pellicci’s greasy spoon cafe on Bethnal Green Road and donating funds to Repton Boys Club, where they started out as juvenile boxers. Word gets around.

The Bailey photograph was part of the ploy but that same vanity and hubris that saw them pursue it undoubtedly ensured their downfall. As the artist himself observed in 2014: “If you’re a real gangster, nobody knows who you are.”

The appeal of the Krays is the same as all outlaws.

They were very male fantasy figures, men who lived out our darkest dreams of transgressing the social rules that restrict us and who enjoyed the spoils of their own daring, wearing sharp tailored suits and swilling champagne in attractive company with money to burn. We still covet the bling and glamour that come with their degree of notoriety.

The Krays also perfectly embodied a very specific moment in London’s cultural history, swaggering down Carnaby Street in the public imagination alongside Michael Caine, The Kinks and Marianne Faithfull.

Looking even further back, they are also sons of the capital’s murky criminal past, belonging in the pantheon of metropolitan ghouls beside Macheath (Mack the Knife), Sweeney Todd, Bill Sykes and Jack the Ripper. In death, they exist in the same mythological gas-lit realm that entices us with visions of gin-fuelled sing-alongs in smokey pubs, pickpockets, wharf rats and prostitutes gathering around the old Joanna to belt out “Knees Up Mother Brown”.

The Krays rose from the same London chronicled by authors Arthur Morrison in A Child of the Jago (1896), and Clarence Rook in The Hooligan Nights (1899). They outgrew the poverty and deprivation they were born into and bent a corner of the city to their will with ruthless violence, two mocking perversions of the social ideal of the self-made man.

Characters like Tommy Shelby in the BBC’s Peaky Blinders occupy the same territory, a creature of Britain’s recent past resorting to desperate measures to claw his way out of the pit. A Robin Hood who can’t be relied upon to give to the poor.

One of the Krays’ “role models” was gangster Billy Hill who dominated 1950s Soho and owned a nightclub in Morocco, modelling himself on Humphrey Bogart.

The influence of the American “tough guy” personified on cinema screens by Bogart and other gangster specialists like James Cagney, Paul Muni, Edward G Robinson and the aforementioned Raft should not be understated.

“Back in the day we looked up to gangsters like [John] Dillinger, Al Capone, Legs Diamond, Bonnie and Clyde – that was what they fed us on, the American films, and I think the British press wanted something like that in this country,” says former Kray henchman Chris Lambrianou, speaking to The Guardian in 2015.

Hollywood began romanticising the gangster in the liberal Pre-Code 1930s, when Warner Brothers produced The Public Enemy and Little Caesar in 1931 and United Artists premiered the original Scarface a year later.

Cagney – actually a very talented song-and-dance man – in particular became associated with the genre, appearing in such crime classics as Angels with Dirty Faces (1938), The Roaring Twenties (1939) and White Heat (1949), his popularity as a bad guy a cause of such concern to the government that he was pressured into appearing in G Men in 1935, in which he turns his brand of hard-boiled pugnaciousness over to work for the FBI.

America’s love of the gangster was a product of the Jazz Age and subsequent Great Depression, when bootleggers defied Prohibition to to bring black market hooch to the people, as documented in HBO’s underrated series Boardwalk Empire (2010-14). The likes of Al Capone were immigrants who became wealthy, powerful men when others had nothing.

Like the Krays, Chicago crime lord Capone was a shrewd self-publicist, setting up free soup kitchens to feed the downtrodden after the Wall Street Crash, a form of social outreach the system had failed to provide at a time when mass unemployment was rife and many were reduced to living in tent cities known as “Hoovervilles” (after hapless president Herbert Hoover) in public parks.

Depression bank robbers like Dillinger, Pretty Boy Floyd, Baby Face Nelson and Bonnie and Clyde were free when the working man was left with nothing. They had get-up-and-go, fast cars and six-shooters. They seized the day, they took destiny by the horns. Their methods may have been immoral but their escapades and getaways provided a gutsier example than a beaten public had become accustomed to, and the sensational press coverage was lapped up.

David Mackenzie’s recent neo-Western Hell or High Water (2016) provided a brilliant update on this sentiment, capitalising on the latest round of recession-inspired anger at the banks to present two brothers raiding vaults in the post-industrial ghost towns of west Texas, something many in its audience might have felt like doing themselves.

Men like the Krays or the characters played by Cagney or Robert De Niro later speak to our frustration about how powerless we feel in our daily lives, constrained by responsibilities and expectations, financial troubles and disappointment. They are sinister projections of our worst instincts.

But the fact that mobsters always come to a bad end ensures the morality tale remains a vicarious fantasy, nothing more.

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.