Indefinite detention must be ended, argue campaigners

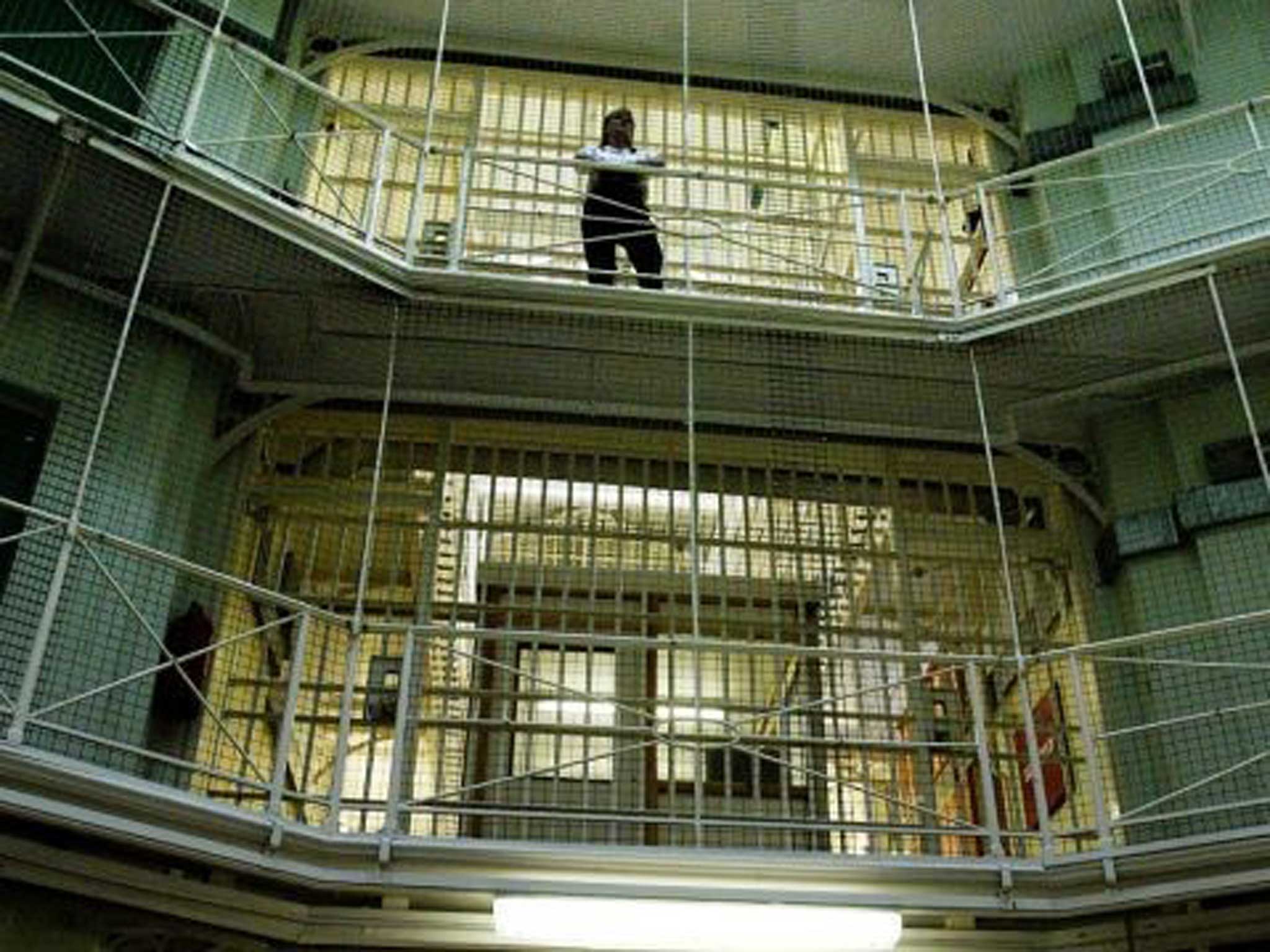

In theory it was abolished, but parole chaos means prisoners are still serving life 'by the back door'

Some refer to it as the waiting game; others call it limbo. Jodie Prin didn't know much about Imprisonment for Public Protection when her partner John was sentenced to a minimum prison term of 21 months for GBH with intent. She remembers thinking that he would be out soon afterwards; she felt positive. "He's the first person to say that he's done something wrong and that he must be punished; you know, 'do the crime, do the time'."

But nine years later, and six years past his minimum tariff, John is still in prison. He is waiting to go before the Parole Board in May, to have his case reviewed for release. The couple have been here before; for every parole hearing over the years, Jodie has been hopeful that John will eventually come home. "There is no end in sight," says Jodie. "He hasn't got a release date. If it warrants 10 years, they should have given him 10 years. Then at least we know what we're facing. But I've got to stay hopeful."

Her partner is just one of the thousands of prisoners in indefinite detention under Imprisonment for Public Protection. Introduced in 2003 but abolished in 2012, IPP sentences were given to those convicted of a serious specified violent or sexual offence and who in the court's opinion, posed a significant risk of harm to the public. It was intended to cover the less serious cases where a life sentence would not be justified. IPP prisoners have no automatic release date. For their release to be considered after they have served their minimum term, the Parole Board must be satisfied that they are no longer a risk to the public.

Widely recognised as a mistake, the IPP scheme trebled the lifer population overnight and quickly swamped the Parole Board's ability to cope. The Prison Reform Trust says more than 5,000 prisoners are currently serving indeterminate sentences despite the abolition of IPP. By the end of last year, more than two-thirds – 3,561 prisoners – had passed their tariff expiry date, and are still waiting to have their case heard by the Parole Board. Of these, 958 were originally given a tariff of less than two years. Experts estimate it will take at least nine years for the backlog to be cleared.

Now legal experts and politicians have called for the Justice Secretary Chris Grayling to speed up the release of IPP prisoners. Lord Lloyd, a former Law Lord, urged Mr Grayling to exercise his power to vary the conditions for release that the Parole Board follows. "How much longer, one can surely ask, will these people have to wait?" he said. The Prison Governors Association has warned that IPP sentences were demoralising both prisoners and staff.

One governor said that IPP prisoners "could see no chance of release as they struggled to access appropriate [rehabilitation] courses... this led to anxiety, resentment and discipline problems".

Lord Wigley, who has campaigned against IPP sentences, has called for IPP prisoners given tariffs of less than two years to be released immediately. He described the situation of IPPs and their families as "grotesque and totally unfair".

"They have no idea of how many years they will remain incarcerated. It is hardly surprising that as many as 24 people on IPP sentences have committed suicide while in custody. It is easy to understand why many people deem IPPs to be 'life sentences via the back door'."

Former UK Supreme Court President, Lord Phillips of Worth Matravers, said the indefinite detention of IPPs for want of resources was "manifestly objectionable". In a Lords debate he said their situation was "unjust" and "economically absurd". He said rehabilitation could sometimes be better provided outside of prison.

The Justice Secretary at the time of the abolition, Kenneth Clarke, acknowledged IPPs were "unclear, inconsistent and have been used far more than ever intended" and were inconsistent with the policy of punishment, reform and rehabilitation.

As part of the need for IPPs to demonstrate that they no longer pose a risk to the public, prisoners are required to take rehabilitation courses. However, insufficient funding means the cash-strapped prison service cannot provide them or else they are inaccessible to prisoners within the period of their minimum tariff. The European Court of Human Rights has already ruled that Britain's failure to detain individuals beyond their tariff without providing rehabilitation was "arbitary and unlawful". The UK is expected to be set for further criticism as several more cases are being lined up for the Strasbourg court.

Lawyers argue it is costing more to keep IPPs in prison without rehabilitation than the Government is saving in cuts to the legal-aid budget. Peter Weatherby, QC, estimated it is costing £250m a year to keep IPPs in detention – £30m more than the £220m legal-aid savings.

The Justice Ministry insists the Parole Board is independent from Parliament and that the Justice Secretary has no plans to retrospectively alter sentences that were lawfully passed before the abolition of IPP.