Hillsborough trial: Timeline of 30-year battle for justice

Latest trial follows two sets of inquests, private prosecutions and civil proceedings over the disaster

The collapse of the latest Hillsborough trial comes after 30 years of legal battles over responsibility for the disaster, which claimed 96 lives on 15 April 1989.

April 1989 onwards

Civil actions seeking damages starts within days of the disaster, both from relatives of the victims and survivors who have suffered physical injuries and psychological effects.

By the following year, more than 700 claims have been lodged and South Yorkshire Police and Sheffield Wednesday FC start making out-of-court settlements “without admission of liability”.

But in November 1991, a House of Lords ruling states that the “chief constable of South Yorkshire has admitted liability in negligence in respect of the deaths and physical injuries”.

August 1989

After sitting for 31 days, the Taylor Inquiry publishes an interim report concluding that “the main reason for the disaster was the failure of police control” and criticising South Yorkshire Police for blaming Liverpool supporters.

Lord Justice Taylor concludes that the most fans were “not drunk, nor even the worse for drink” and highlights contributing factors including opening exit gates to allow fans into the ground and failing to delay kick-off.

The report says a pitch invasion “was unlikely at the beginning of a match” and there was “no effective leadership” to organise rescue efforts or relieve pressure from behind the pens where the crush happened.

Sheffield Wednesday FC is also criticised for an inadequate number of turnstiles at the Leppings Lane entrance and the poor quality of crush barriers on the terraces, some of which collapsed during the disaster.

The Taylor Report causes UK-wide changes to football stadiums, seeing fencing removed and standing terraces converted to seating areas at large venues.

August 1990

The Crown Prosecution Service decides that following consideration of “all the evidence and documentation”, there is “no evidence to justify any criminal proceedings” against South Yorkshire Police officers, Sheffield Wednesday FC, Sheffield City Council or Eastwoods – the structural engineering firm that designed the pens.

Members of the public make 17 complaints that are considered for disciplinary action, which is recommended for David Duckenfield and Bernard Murray, who was ground commander on the day. The Police Complaints Authority (PCA) find there is sufficient evidence to charge them with “neglect of duty” but Mr Duckenfield is on sick leave during the process, and retires on medical grounds in November 1991.

Following judicial advice, the PCA decides against proceeding against Mr Murray alone.

November 1990

Inquests open in Sheffield, heard by the local coroner, and South Yorkshire Police renews its argument that drunk supporters who arrived late and without tickets contributed to the disaster.

The inquests become controversial after Dr Stefan Popper limits their scope to events up to 3.15pm on the day of the disaster – just nine minutes after the match was halted – and excludes the witness evidence of two doctors inside the stadium.

Bereaved families are angered that the inquests cannot consider the emergency response after that point, and an accidental death verdict is returned on 26 March 1991.

March 1993

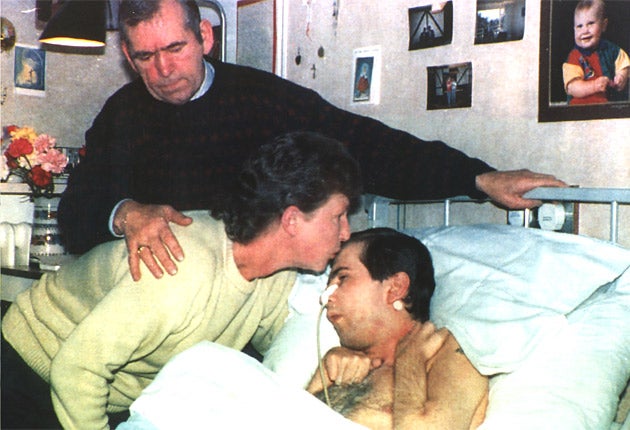

The decision is taken to withdraw feeding and hydration from 96th victim Tony Bland, who has remained in a persistent vegetative state since receiving his injuries at Hillsborough. Because of the length of time between the disaster and his death, the law does not allow Mr Duckenfield to be charged with Mr Bland’s manslaughter.

November 1993

The High Court rejects an application for judicial review of the inquest verdicts brought by six representative families.

Lord Justice McCowan says he can “see no fault in the coroner” for cutting off the scope of the inquests at 3.15pm because he relied on medical evidence, and refuses to quash the verdicts.

December 1996

Following the broadcast of a television dramatisation of the Hillsborough disaster, the Home Office’s Operational Policing Policy Unit writes to Michael Howard, then home secretary, saying it raises the “suggestion that some of the victims were still alive at 3.30pm”. There are renewed calls for a fresh inquest or public inquiry.

The following March, a Home Office meeting consideres material submitted by the Hillsborough Family Support Group (HFSG) calling for a new inquiry but advice to the attorney general says the 3.15pm cut-off had been “fully justifiable”.

The then Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) concludes that there is “no new evidence as alleged by the HFSG and their legal representatives, and therefore no grounds for reopening the police investigation into the Hillsborough disaster”.

June 1997

The new Labour government’s home secretary, Jack Straw, notes the discussions but said “public concern will not be allayed by a reassurance from the Home Office that there is no new evidence” and proposes an independent review.

The new “scrutiny” is conducted by Lord Justice Stuart-Smith. A handwritten note apparently written by Tony Blair, asks “why? What is the point?”.

The scrutiny goes ahead but in February 1998, Lord Justice Stuart-Smith rejects grounds for quashing the accidental death verdicts or bringing prosecutions.

August 1999

The HFSG is granted permission for a private manslaughter prosecution against Mr Duckenfield and Mr Murray.

In February 2000, both officers appeal to the Divisional Court but fail and the trial is held in Leeds between 6 June and 24 July 2000. Mr Murray is acquitted and the jury is undecided on David Duckenfield. Application for a retrial is refused.

April 2009

Following a public announcement by Labour minister Andy Burnham, concerning the possible early release of Hillsborough-related documents, the HFSG meets with the home secretary and the Hillsborough Independent Panel is set up.

September 2012

After reviewing 450,000 documents, the Hillsborough Independent Panel publishes a report highlighting police failings and the alleged campaign to blame Liverpool supporters for the disaster.

Crucially, the panel finds that 41 victims did not have signs of the crush injuries originally claimed by pathologists, and so may have been saved.

The finding undermines the decision made by the coroner in the first inquests to limit their scope to events before 3.15pm, and not consider the chaotic medical response after that point.

Home secretary Theresa May orders a new criminal investigation into the disaster, Operation Resolve.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission launches an investigation into an alleged cover-up by officers in the aftermath of the disaster.

December 2012

The High Court quashes the original inquest verdicts of “accidental death” and orders new inquests.

Attorney general Dominic Grieve had made an application based on the Hillsborough Independent Panel’s report.

March 2014

The new Hillsborough inquests start in Warrington, and go on to become the longest case ever heard by a British jury.

April 2016

The inquest jury concludes that the 96 victims were “unlawfully killed” and that Liverpool fans’ behaviour did not contribute to the crush.

The findings heavily criticise the police operation, stadium layout and design, and local ambulance service.

June 2017

The Crown Prosecution Service announces that six people are to be charged with offences in relation to the disaster – Mr Duckenfield is charged with manslaughter and former Sheffield Wednesday club secretary Graham Mackrell for health and safety offences.

Solicitor Peter Metcalf, former chief superintendent Donald Denton and former detective chief inspector Alan Foster are all charged with perverting the course of justice.

December 2017

The CPS announces that a police officer and a farrier will not be prosecuted over allegations that they fabricated a story about a police horse being burnt with cigarettes at Hillsborough. The farrier’s prosecution for perverting the course of justice is found not to be in the public interest and there is insufficient evidence against the police officer.

June 2018

A judge lifts the historic stay of further prosecution on Mr Duckenfield, allowing new proceedings to go ahead. Abuse of process arguments for other defendants fails.

August 2018

The CPS announces that all charges against Sir Norman Bettison are being dropped because there is insufficient evidence for a realistic chance of a conviction, which is the test for all prosecutions.

The death of two witnesses and contradictions in the evidence of others is cited as part of the reason for the decision.

October 2018

Judge Sir Peter Openshaw rejects a defence application to ban reporting on the Hillsborough trial until the jury delivers its verdict. He also rejects a prosecution application to prevent tweeting from court, sharing articles on social media or embedding video into news articles.

January 2019

The trial of Mr Duckenfield and Mr Mackrell starts at Preston Crown Court.

April 2019

Jury fails to reach a verdict on the charges against Mr Duckenfield, but convicts Mr Mackrell of a health and safety offence.

May 2019

Mr Mackrell is fined £6,500 for the offence, sparking outrage from victims’ relatives who called the penalty “shameful”.

October 2019

Mr Duckenfield’s retrial starts at Preston Crown Court.

November 2019

On 1 November, a juror is discharged after telling fellow jurors ”dickhead Duckenfield needs to die”, but the judge rules that the trial can proceed.

A second juror is discharged on 19 November after suffering a bereavement, leaving a jury of seven women and three men to decide the case.

On 28 November, the remaining jurors acquit Mr Duckenfield of gross negligence manslaughter, as the investigating police officer says the delay between the disaster and the trial should not have been allowed to happen.

Early May 2021

Jurors hear how a PC’s account of the disaster was changed to remove criticisms of police, but notes about drunk fans were kept in.

PC Maxwell Groome was on duty for the match at Sheffield Wednesday’s stadium.

Late May 2021

The trial against retired Ch Supt Donald Denton, 83, retired Det Ch Insp Alan Foster, 74, and former solicitor Peter Metcalf, 71, collapses.

They applied to have the case against them dismissed after a month of evidence in a trial that had been awaited for decades by the victims’ families.

Sue Hemming, the CPS’ director of legal services, reacts to the decision by issuing a scathing statement. “What has been heard here in this court will have been surprising to many,” she said.

“That a publicly funded authority can lawfully withhold information from a public inquiry charged with finding out why 96 people died at a football match, in order to ensure that it never happened again – or that a solicitor can advise such a withholding, without sanction of any sort, may be a matter which should be subject to scrutiny.”