'Hillsborough took away my life' - a survivor's story of the 1989 disaster

It was something special to be a Liverpool fan in April 1989. “You would go to games and you knew you were going to win. It was just a question of how many goals you would score,” explained Kenny Derbyshire.

Then aged 22, the lifelong Kop season ticket holder had travelled in spring sunshine from his home near Anfield over to Sheffield with 15 mates in the back of a Transit van to watch his team play Nottingham Forrest in the FA Cup semi final at Hillsborough.

Despite the shame and horror of Heysel when 39 fans died in hooligan clashes during the club’s European cup final against Juventus in Brussels four years earlier - these were heady times for Liverpool FC’s fanatical army of travelling followers.

The sporting success of the city’s leading club contrasted dramatically with Merseyside’s economic fortunes during the 1980s. Since the dawn of the decade they had already clocked up six First Division titles, two European Cups and the FA Cup – a trophy the team was to go on to win again five weeks later in an emotional derby against Everton.

But by the time fans started arriving at the Leppings Lane end, massing in front of the ground’s outdated turnstiles, the problems started to become apparent.

“I can remember every moment of that day from when I got up to the moment I went to bed,” says Mr Derbyshire.

“It was the same as a normal match but you knew something was wrong as soon as you got to the ground,” explains the quietly spoken 46-year-old. “I was in the tunnel (which led to the Liverpool end) for 20 minutes before I got out. You were levitating – floating backwards and forwards.

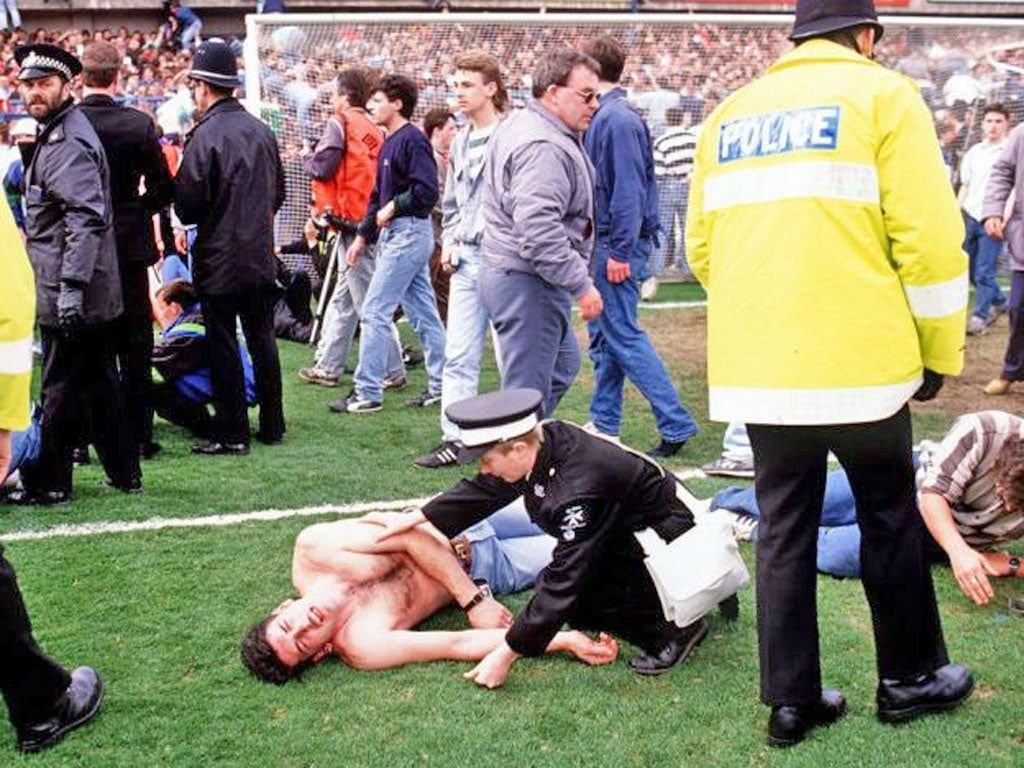

“You could see nothing, your hands were by your side. Then all of a sudden the barrier collapsed and I managed to climb up. Someone pulled me out,” he recalls.

Mr Derbyshire insists there was no conspiracy by ticketless fans to rush the gates. No excessive drunkenness and no violence.

Once they had made it clear of the crush Mr Derbyshire and his friends who all survived were ordered to leave the ground and make their way back home as best they could.

Four hours later after being shepherded onto a special train back to Lime Street he queued at the phone box to ring his parents to tell them he was alive.

“This was before anyone had a mobile phone. That was the worst part not knowing what happened to our mates who were in there. All the police wanted to do was get us out of there as quick as possible,” he says.

The effects of that day have overshadowed everything that has followed. “Hillsborough took away my life,” explains the quietly-spoken fork lift driver.”

It is hard to cope with sometimes. It is the first thing on my mind in the morning and the last think about when I go to bed. Every day, 365 days a year,” he says.

“It is running through my head like a video tape: people screaming for help but that help never arrives – they were in pure pain and agony, that’s what goes through my mind most of all.”

Mr Derbyshire has little sympathy for those that blame the fans. “Liverpool supporters have been criticised for what happened that day but to my eyes they were the heroes. They saved more lives. They were the first to take action – to make down the advertisements to make stretchers to ferry the injured to the touchlines,” he says.

Despite the trauma he has remained loyal to his boyhood club. “It’s still the same passion. But some (of the survivors) have stopped going to the games – they couldn’t handle it any more.” he explains.

“I know the truth because I was there. I blame three organisations: the FA for giving us the smallest allocation even though we had the greatest number of fans; Sheffield Wednesday for operating the ground without a safety licence and South Yorkshire Police,” he says.

“Hooliganism was rife in those days and everyone thought it was a pitch invasion but you can tell the difference between a pitch invasion and when people are crying for help. They were pushed back by the police. They had tears running down their faces screaming for help but their pleas were ignored.

“The help wasn’t there for them – they were totally ignored. A lot more lives could have been saved that day if the help had been there,” he recalls.