Hatton Garden heist: The target, the plan, the job, the gear and the investigation behind the biggest burglary in English legal history

Searches revealed jewels and cash under microwaves, behind skirting boards and hidden behind kitchen kickboards

The secret video camera perched on the end of the bar at The Castle pub in north London captured three elderly men at a corner table sipping mineral water and indulging in quiet conversation.

The date was May 1, 2015 – the blackboard above them advertised the gastropub’s upcoming summer party – and they were basking in the successful afterglow of a job apparently well done.

The trio were a common sight at the pub where they had met every Friday to plot a raid on the Hatton Garden Safety Deposit centre. Now, nearly four weeks after the job, they had to work out how and where to divide the remainder of the £14 million proceeds that hadn’t been salted away, or already whisked out of the country.

And in the quiet pub they could not resist recounting how they finally broke through the walls of the vault and sent the metal cabinets holding gems and gold crashing to the floor. “Boom,” said Terry Perkins, 67, one of the ringleaders, and he mimed the action of an explosion.

What Perkins – a career armed robber of some repute and experience – did not appreciate was that he and his colleagues had been under surveillance for at least a fortnight.

Despite the shadows and the partially hidden faces, a specialist lip reader was able to decipher fractured sections of their conversation from the footage of the disguised camera which made it clear that they were talking about Hatton Garden. Eighteen days later they were all under arrest.

The public discussion of their crime was just one of a series of blunders that finally undid the team of geriatric criminals and their ailing associates, seeking one final hurrah to achieve criminal superstardom.

“If we get nicked at least we can hold our heads up that we had a last go,” said Danny Jones, one of the four ringleaders.

The Team

The elder statesmen of the Hatton Garden jewellery raid had known each other for years. Perkins, 67, and Brian Reader, 76, – the man known as the guv’nor – had together taken part in major jobs and served time inside together. They had been talking together for months about pulling the Hatton Garden job, which would become the biggest burglary in British legal history.

Reader had a reputation as one of the country’s most audacious burglars of his generation, even if his thin criminal record suggested otherwise. He did go on trial in 1982 for stealing £1.3 million in a series of burglaries that included Hatton Garden, but the trial collapsed after an alleged attempt to nobble the jury.

While on bail for the retrial, he went on the run to Spain with his wife. Family illness cut short his life on the lam and he slipped back into Britain with his wife in 1984, to team up with Kenneth Noye, the Kent criminal currently serving life for a road rage murder, who he’d met at a wedding five years earlier.

The pair’s notoriety was ensured by the 1983 Brink’s Mat gold bullion robbery and its bloody aftermath. They were not involved in the raid, when a robbery team escaped with gold worth £26m, but were brought in to shift the bullion.

Their attempts to do so attracted the attention of the police, who placed an observation team on the pair who were watching as Reader met Noye at his substantial Kent home. Venturing into the garden of his substantial Kent home to discover why his dogs were barking, Noye stumbled on the unfortunate DC John Fordham, a veteran surveillance officer.

Noye later claimed that he thought the man was an intruder intent on attacking him, and stabbed him to death. Noye and Reader were both charged with his murder but were acquitted, though Reader was later jailed for nine years for his role in laundering the Brink’s Mat cash. He had effectively gone into retirement in Dartford when more than 30 years later, he was to be given the opportunity for another crack at Hatton Garden.

Terry Perkins’ life had been framed by the other big job of 1983, the Security Express depot robbery, then Britain’s largest ever cash raid, of £6m. Although it employed similar tactics – an inside job, terrified guards doused with petrol – the raid was carried out by a different team.

Undone by the confessions of fringe plotters, Perkins was jailed for 22 years. In 1995, as he neared the end of his sentence, he walked out of Spring Hill prison in Buckinghamshire. He was eventually returned to prison and only finished serving his sentence in 2012. He was to get back to work quickly.

He lived just a mile-and-a-half away from Jones, in Enfield, north London, who also a long criminal past, with jobs similar to that at Hatton Garden. He had been questioned at length over his role in a similar crime to drill into a vault in London’s Bond Street, though on that occasion he had never been charged with a crime, it can be revealed today. Police are still investigating that crime.

Jones, a crime obsessive, had learned of the criminal abilities of Brian Reader from a disaffected acquaintance of the geriatric prisoner in the cell next door during one of his periods behind the door at Maidstone Prison. The fourth of the ringleaders John ‘Kenny’ Collins, also had a long history of crime, including a £300,000 jewellery raid in west London in 1988, for which he was sentenced to nine years in prison.

The Target

Hatton Garden Safety Deposit is a long-standing institution in London’s jewellery district, patronised by the jewellery trade and the criminal fraternity, who all cherished its anonymity, security and discretion.

The 996 safety deposit boxes were held in a vault in the basement of a building that extended over seven floors and had more than 60 tenants above the basement holding the security box centre. Setting up a box was easy, requiring little more than identification and a monthly payment of rental, according to former users.

Whenever anyone wanted to access their box, they would show their credentials and be ushered downstairs. They held the two keys needed to get into the box, and the safety deposit centre would be none the wiser about its contents.

An underworld source – who used the centre to stow cash and jewellery for a “rainy day” – told ‘The Independent’ that he had emptied his box some years before the raid, but said that associates continued to use it, including one east London drug dealer murdered last year.

The source, himself a drug dealer, said that a lieutenant of the feared Adams family crime syndicate who supplied him with class-A drugs had recommended the use of the safety deposit centre.

This so-called A-team, run by a feared triumvirate of brothers, had controlled the drug trade across parts of the capital in the 1980s and 90s.

One of them, Tommy Adams, was a contact of Brian Reader at the time of the Brink’s Mat job. The pair had been spotted by a surveillance team with a Hatton Garden gold dealer in 1985 during discussions about how to turn the gold into cash from the raid.

The centre had been taken over seven years ago by the Bavishi family from Sudan but security was largely the day-to-day responsibility of two long-serving guards.

The vault itself was a small room with the walls covered with metal cabinets bolted to the floor and ceiling. The vault itself was protected by a large combination-coded door, and thick walls.

The set-up and practices had barely changed since it was first installed in the 1940s. The lift that served the building had stopped going down to the basement three decades before after an intruder with a shotgun had tried to break in. But even when the Bavishi family took over, the entry codes had not been changed.

The gang had little sympathy for the people they were about to hit. Perkins recounted how he discovered that his daughter’s engagement ring, bought from Hatton Garden, had a fake among the six mounted stones. “They deserve all they get, Dad,” was her response, he said.

The Planning

Danny Jones had been researching drills that could break into a vault on the internet from August 2012. He had also researched the price of gold and diamonds.

The gang also carried out reconnaissance on the deposit box centre itself. Lionel Wiffen, a jeweller who worked next door, had felt uneasy from January 2015 and said that he had the feeling of being watched.

The vault was only opened to key staff and box holders, but one long-serving security guard had allowed four or five potential customers to look around the vault in the year before the attack. Were any of those “customers” involved in the raid? There was evidence that members of the gang also got into the building to prepare the ground for breaking into the vault.

A few days before the burglary, a woman working for a diamond company inside 88-90 Hatton Garden found herself waiting a long time for the lift. When it finally arrived, the doors opened to reveal a man aged around 60 wearing blue overalls and surrounded by tools and building equipment. The description fitted that of Perkins.

The gang also made preparations for shifting the proceeds of their crime if they were successful. ‘The Independent’ has learned that a prominent fence in west London - who specialises in shifting “hot property” out of the country – was contacted in late 2014 about receiving high value jewels.

His modus operandi was to take the most valuable jewellery, weave it into rudimentary costume jewellery and give it to women to wear on budget flights to Europe within hours of a robbery being committed. There the jewels are re-cut and sold on – sometimes back through Britain. Perkins also made regular meetings to London City Metals, a scrap metal dealership in Silvertown, East London.

The Job

They chose the Easter Bank Holiday weekend to strike, just as Perkins had done with the Security Express job 32 years earlier, because their targets would be lightly staffed.

The gang was already on the move when Kelvin Stockwell, one of the two main security guards, set the alarm on Thursday, April 2, and left at around 6pm, not expecting to return until the following Tuesday morning.

They began their attempt to get into the building even as Mr Wiffen, the jeweller, was dealing with clients and clearing up before the long holiday weekend.

There were two locked routes into the building before the gang could even think about tackling the vault and each route was subject to its own unique challenges.

The first man in was a man caught on police probes of the defendants being called “Basil”, the only member of the team yet to be identified, whose shock of red hair suggested that he was wearing a wig.

He walked through the front door of 88-90 Hatton Garden, either using a key or managing to push something through the letterbox to turn the handle from the inside.

Inside, Basil was immediately confronted with a magnetic door that needed a four-digit pincode. It was not clear if he had the code or used a £20 tool to get in. From there he crossed the lobby and unlocked another door that led downstairs to the basement and the entrance of the Hatton Garden Safety Deposit centre.

Basil waited until Mr Wiffen left the building a few minutes later just after 9.20pm via the second entrance, a fire exit that connected to a basement courtyard outside the safety deposit centre.

After Mr Wiffen left and locked the door behind him, Basil was spotted by CCTV cameras in the courtyard and let the rest of the gang in through the fire escape. The gang hauled in wheelie bins, steel joists and tools. But they were still only at the entrance of the security box offices.

They were still faced by a locked door, two iron gates, and the formidable vault. They were able to evade some of the security by getting in down the lift shaft, after Perkins had disabled it and ensured it did not move from the second floor.

By forcing open the doors on the first floor, a member of the gang – probably Basil – dropped the short distance into the basement and slid open the gates of the disused lift entrance in the basement from the inside.

This method of entry had the advantage of bypassing two doors and an alarm system, which would have sounded within 60 seconds of the outer door being broached, unless a security code was tapped into it.

It was to that alarm that Basil first turned, ripping off the aerial and cutting wires, drastically reducing its range, but not completely disabling the system.

It was an error that nearly proved fatal to the plan. With the alarm apparently switched off, they wrenched open the metal door that separated Basil from the rest of the gang and allowed them all inside.

The breaching of the metal door appears to have allowed the weakened alarm system to send a radio signal to the security company monitoring the system. It alerted the owner, Mr Bavishi, who sent one of his guards to check what was happening, and rushed to join him.

Perkins later referred to the incident during a secretly recorded conversation. “Still don’t know how he [Basil] let that alarm go off. It wasn’t one that they confirm. Basil would… make some shit up. I don’t know enough to challenge him, you know what I mean? He can baffle me with bullshit.”

Mr Stockwell, the security guard, was sent to the building but found the two entrance doors secure. A few years earlier an insect had set off the alarms, so he called up Mr Bavishi and wrongly told him that it had been a false alarm. The police – who had also been alerted by the alarm company - did not turn up, leaving it to the company’s staff to check out.

It was a narrow escape. Did the gang know what had happened? The fourth ringleader, John ‘Kenny’ Collins – a veteran thief of more than 50 years’ standing – was posted in a building over the street and was communicating with the vault team by walkie-talkie. He may have seen Mr Stockwell check the building and then head for home.

Aided by this slice of luck, they pressed on and focused their attention on a final gate and then the main vault, protected by an awesome Chubb lock.

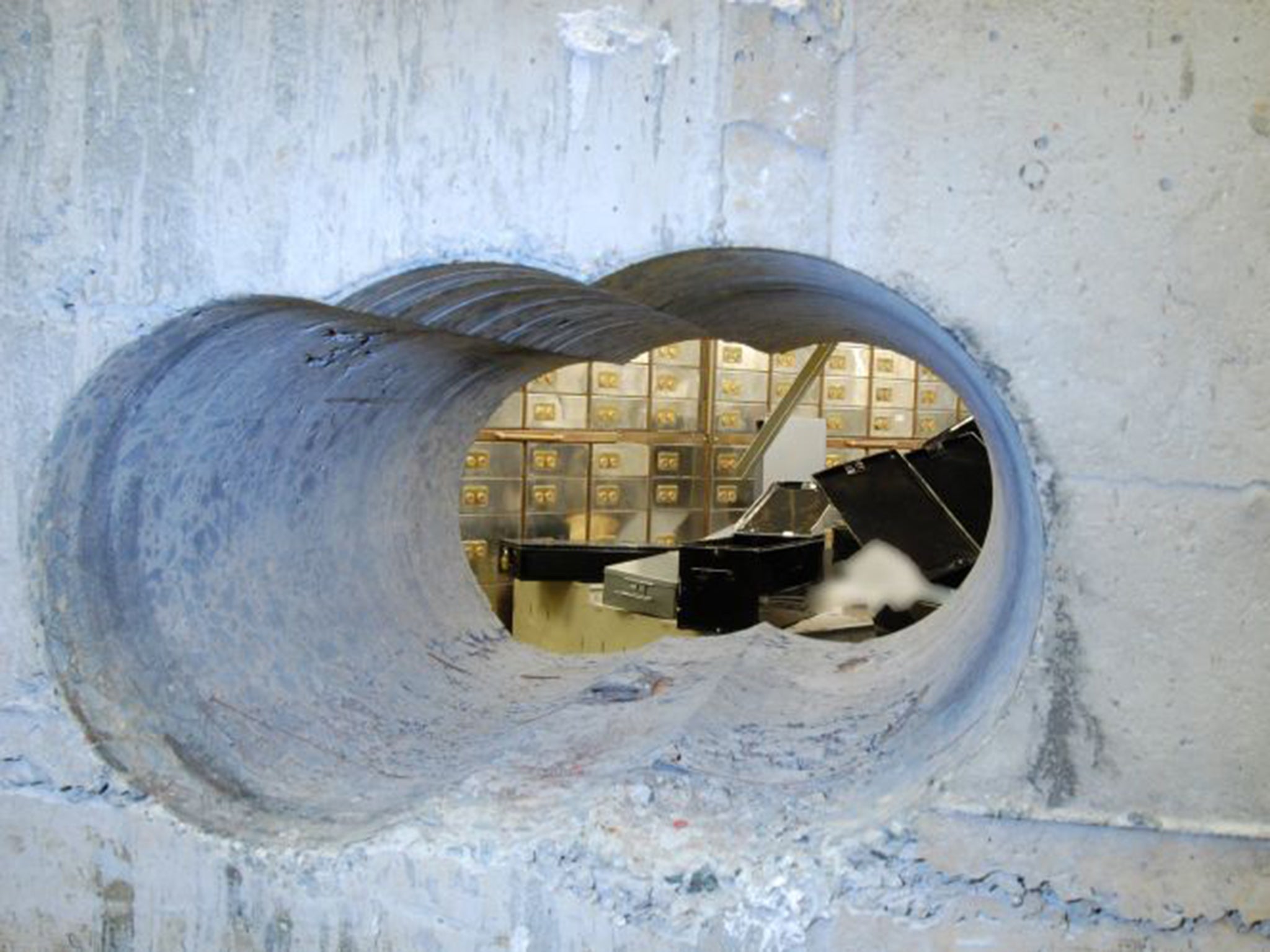

Instead of tackling it, and aided by the internet research of Jones, they fixed an industrial drill to the wall, to make three adjoining holes in the thick concrete walls, big enough to squeeze a man through.

Their difficulties were not over. While they broached the walls, they came up against the metal cabinets lining the walls that held the safety deposit boxes. A ten tonne hydraulic ram brought in to knock them down probably broke.

It was clear that tempers inside the vault were becoming frayed among the frail burglars. Carl Wood, a member of the burglary team, was walking round in circles on the first night screaming like a pig, according to conversations among the plotters picked up by police probes. “I said: ‘Carl do something for fuck’s sake’,” recounted Jones, overheard by a secret police probe after the crime. “It was fucking pricks we were with.”

Less than 11 hours after they first got into the building, the burglary team emerged on Good Friday morning leaving the fire door ajar and without a gem to their name.

Thrown by the failure of their initial plan, the plotters made a series of mistakes. Jones and Collins travelled to Twickenham to buy a new pump to replace that one that had broken.

Jones signed the customer details as V. Jones, giving most of his address. An eccentric man given to sleeping on the floor wearing his mother’s dressing gown and a fez, he liked to be known as Vinnie Jones, after the hard man of football and latterly gangster movie fame.

On the Saturday night, they returned, first Collins driving up in his Mercedes to check out the area before a white van pulled up carrying the team – without Reader, who failed to return on the second night. He was swiftly joined by Carl Wood who walked off into the night after getting cold feet when he discovered that the fire exit had been relocked by an unwitting Lionel Wiffen, the jeweller who had discovered it ajar when he returned to clean his offices.

The departures of Wood and Reader – once described as the ‘master’ - were treated with disdain by the rest of the team. “They are both as bad as one another as far as I’m fucking concerned,” says Perkins. “They’re both arseholes.” He spared particular ire for the 76-year-old Reader, an “old ponce” who he says spent his days sitting in a South-east London café “talking about all our yesterdays. He bottled out at the last minute. He’s supposed to be a full-on face. He’s not going to work again.”

He added: “He was a proper thief 40 years ago.”

The pair missed out on the pay day. The new pump worked and rammed the cabinet clear of the wall, popping the bolts that held it fast and sending it tumbling down to the ground – as Perkins was to describe in the Castle Pub four weeks later.

They jemmied open more than 70 security boxes and escaped with sacks of jewellery and gold piled into wheelie bins, leaving no forensic trace.

In the Security Express raid in the 1980s, the team turned away some of the cameras so they did not capture what had gone on. On this job, they ripped out the CCTV system’s hard-drive in the belief that it controlled all of the cameras in the building. On that, they were wrong.

Shifting the Gear

Terry Perkins knew from painful experience that the more people knew about a job, the more likely it was to unravel.

Perkins, a self-styled property magnate, had worked on the 1983 Security Express robbery with a group of men whose involvement read like a Who’s Who of the celebrity criminal underworld of the 1980s. They included Ronnie Knight – Soho strip joint king and the husband of Barbara Windsor – and Freddie Foreman, the former enforcer for the Krays. But they were all men who did not talk. Perkins was convicted after a garage owner on the periphery of the plot cracked under police questioning and revealed all that he knew. He got a 22-year stretch.

So when he discovered that Collins had brought others into the plot, including Collins’ 74-year-old brother in-law Bill Lincoln, he was furious.

“I said, ‘Ere, how does this fucking Bill [Lincoln] know about anything’,” he said. “I went upstairs to have a shower right and when I came down there was a bloke here who I never knew, which was Bill, and Kenny [Collins] had told him everything.”

That meeting was at Bletsoe Walk, Islington, the home of Collins, as the proceeds of the heist were divided and hidden until the heat was off the group. The most valuable stones were already out of the country.

One man who did not get anything was Wood, who walked off the job on the final night despite having debts of £20,000.

The Investigation

Security guards raised the alarm on April 7 when they returned to work after the Easter holiday break. There were big holes in the wall, an abandoned drill, and metal cabinets on the floor, but the gang had left no forensic trace behind. They took on the most valuable items, leaving behind personal effects including military medals and intriguingly a tape recording of an undisclosed confession.

The raid on Hatton Garden had not been the Metropolitan Police’s finest hour. They apologised for failing to turn up when the alarm went on the first night, admitting that “systems and processes” were not followed. The whiff of incompetence was not helped by the ‘Mirror’ newspaper securing footage of the raid from a separate jewellery business before investigators got hold of it themselves. A senior officer later complained that they had been portrayed like “Keystone Cops”.

But in their attempts for a swift result, they were aided by the mistakes of the plotters. The old school criminals were also found out by investigative techniques - notably the use of the network of cameras that identify car movements from the number plates – that were not available during their criminal heydays of the 1980s.

The crime had all the hallmarks of having information from the inside because of the way they had managed to get into the building, and one of the security guards, Kelvin Stockwell, said that he had believed it to be an inside job.

They seized two hard drives containing CCTV images – targets that would have been identified if inside information had been secured – but they missed one camera, controlled by the jewellery business. Triggered by movement, that camera showed some of the burglars arriving and leaving the scene.

CCTV outside the building showed the gang’s van but also, significantly, the Mercedes belonging to Collins on his second-night recce.

Eleven days after the burglary, a police surveillance team followed Collins into the Moon Under Water pub in Enfield where he met emergency plumber Hugh Doyle, who helped hide the jewels. Within another eight days, the surveillance team had spotted all the ringleaders as they met to arrange bringing the loot back from various hiding places to be divided up properly, now that the initial hullaballoo had died down.

The men were spotted in cafes including Scotti’s, an institution in the Clerkenwell district of London.

Detectives also placed probes in the cars of Collins and Perkins, which provided a rich seam of evidence as they boasted about their crime, slated the men who had walked off the job, and discussed how they were going to split up the proceeds.

Jones – playing the role of Perkins’ acolyte – praises the older man for his twin successes in the Security Express raid and the Hatton Park job. “The biggest cash robbery in history at the time, and now the biggest tom [Cockney rhyming slang: Tomfoolery is Jewellery] history in the fucking world, that’s what they are saying…. And what a book you could write, fucking hell.”

The burglars had discussed the prospect of being arrested. Perkins – a man who needed insulin and 20 pills to get him through the burglary - said he would tell officers: “I’ll say, what, you dopey cunt? I can’t even fucking walk.”

The exchange was scheduled to take place at a car park at the Wheatsheaf pub in Enfield, next to where Doyle had a workshop for his plumbing business. Once it happened, the police moved in – arresting the men in their cars and at their homes. But officers secured at best only a third of the £14 mestimated haul.

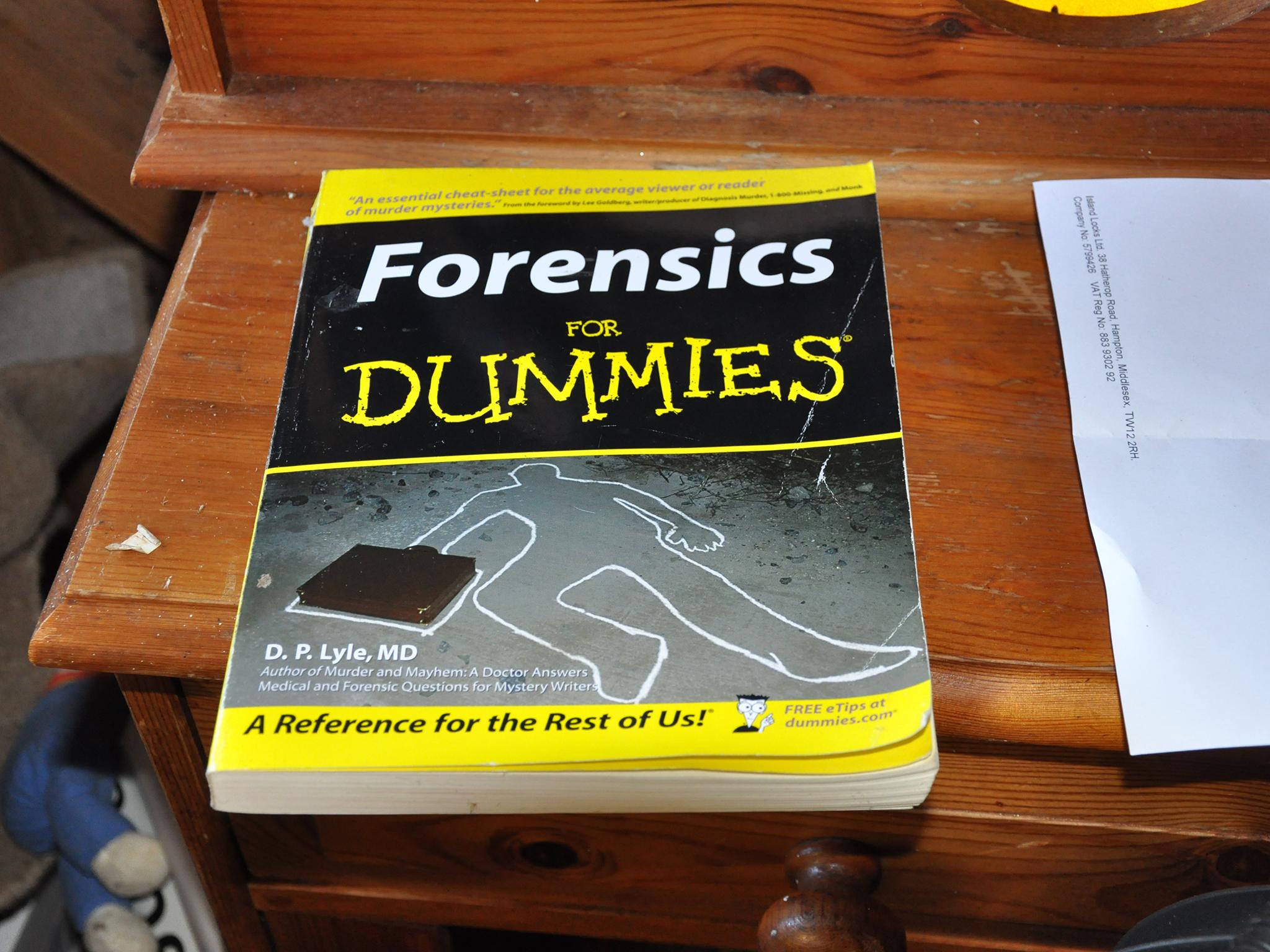

The searches revealed jewels and cash under microwaves, behind skirting boards and hidden behind kitchen kickboards. At Jones’s luxurious Enfield home – where a carved skull decorated the bannister - police found a receipt for a £20 “bypass tool” that would have allowed someone to get through locked doors at Hatton Garden and a book, “Forensics for Dummies”, in a garden cabin.

At Reader’s house, detectives found diamond-testing equipment and a book that promised to tell the “true story of ‘Flash Fred’, the world’s most famous diamond agent”. They also found the distinctive scarf he was wearing on the first night of the raid as he headed down to the vault, captured by CCTV.

At the home of Perkins, they found jewels and the blue overalls thought to have been worn by the man working on the lift just before the raid. At Wood’s home nothing was found, in keeping with his pariah status after walking out on the burglary team.

Even when the gang were remanded in custody awaiting their trial, they could not resist cocking a snook at authority. Conspiracy to burgle carries a maximum jail sentence of ten years. Time is given off for an early guilty plea and other factors including health, age, expressions of remorse and “demonstration of steps to address offending behaviour”.

The latter factors may have explained Jones’s decision to write to the Sky News crime correspondent, offering up his loot to the police, and describing himself as a “burnt-out burglar”. He complained that police would not allow him out of Belmarsh top security prison to show them where he had stashed it. “I'm trying my best to put things right and for some reason they don't want me to give it back,” he wrote. “If I don't get the chance to go out under armed escort, I hope some poor sod who's having it hard out there with his or her family find the lot and have a nice life, as you never know, Martin, people do find things, don't they?”

Unknown to Jones, police had been making their own inquiries which led them to Edmonton cemetery and the memorial plot of his partner’s father. After lifting off the memorial stone, they found two bags holding large amounts of jewellery.

A week later, they took Jones out of prison. He had no idea that they had already uncovered some of his hidden loot. He took them to a different stone and a smaller amount of jewels. “There’s no outstanding property. That is all I had,” he told police. “The rest of it you got on the day.”