Hillsborough trial verdict: The families’ 30-year fight for justice continues

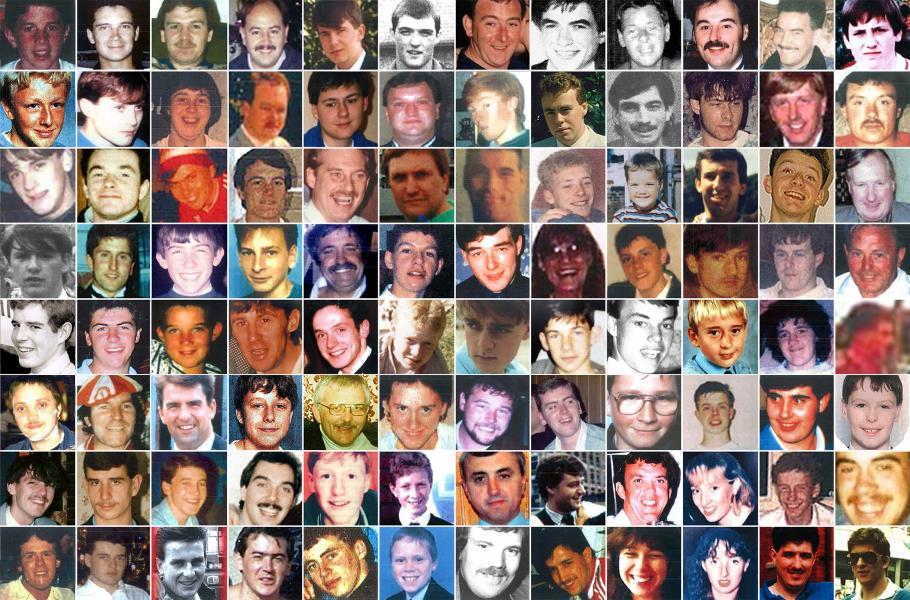

Relatives of the 96 have never given up, even when powerful political and media figures have tried to portray innocent fans as ‘tanked-up yobs’ who stole from the dead after causing a tragedy

The people in authority underestimated them.

They underestimated them in an era when football fans were often regarded as hooligans or brainless “turnstile fodder”, when a policeman could allegedly tell a supporter trying to raise the alarm about the unfolding Hillsborough disaster to “shut your f***ing prattle”.

They underestimated them when they thought a city brought to its economic knees in the 1980s would lack the strength to fight a narrative that turned innocent supporters into “tanked-up yobs” who caused a tragedy then stole from the dead and “urinated on brave cops”.

But the people of Liverpool did not “shut their f***ing prattle”.

They united around the bereaved families of the Hillsborough dead. They organised.

The supporter who tried to alert the policeman, Trevor Hicks, lost his daughters Sarah, 19, and Victoria, 15, when they died in the crush in the Leppings Lane terrace and he became a key figure in the Hillsborough Family Support Group.

And so began a dogged campaign for justice that led to David Duckenfield, the man who commanded the police at Hillsborough on 15 April 1989, being put on trial for gross negligence manslaughter nearly 30 years later.

The jury was unable to reach a verdict today and the Crown Prosecution Service has said it will seek a retrial. That, however, does not diminish what the Hillsborough families and the people of Liverpool have achieved since a football match became a tragedy.

It is easy to forget just how different attitudes were in 1989.

Everyone now can see the abhorrence of The Sun’s front page which, four days after Hillsborough, claimed to offer “The truth: some fans picked pockets of victims, some fans urinated on the brave cops, some fans beat up PC giving kiss of life.”

Even The Sun has apologised.

But in 1989 few knew that senior members of South Yorkshire Police had edited 164 statements from their own junior officers, in what would eventually be condemned as an attempt to create a narrative focused on allegations of “drunkenness, ticketlessness and violence”.

The 1985 Heysel Stadium disaster was fresh in many minds; Liverpool fans were held responsible for hooliganism that led to a five-year ban on English football clubs playing in Europe.

The Sun’s readership, encouraged to see Harry Enfield’s Loadsamoney character as a role model rather than satire, were probably not well-disposed towards the people of an economically deprived city with a reputation for hard-left Militant politics.

The view that Liverpool “hooligans” must somehow have been responsible for Hillsborough might even have stretched all the way up to the entourage of Margaret Thatcher, a prime minister not known for her love of football, or its supporters.

It was Thatcher’s press secretary Sir Bernard Ingham – not The Sun – who coined the phrase “tanked-up yobs” to describe Liverpool fans. The day after the tragedy, he and his boss had been shown round Hillsborough by senior officers of South Yorkshire Police.

“I know what I learned then,” Sir Bernard wrote in a rather extraordinary letter of December 1996. “There would have been no Hillsborough disaster if tanked-up yobs had not turned up in very large numbers to try to force their way into the ground.

“Innocent people who, by virtue of being in the ground early, had their lives crushed out of them by a mob surging in late.”

Almost as if the heady days of Thatcherism had never ended, Sir Bernard told his correspondent, who had lost a friend in the disaster: “Liverpool should shut up about Hillsborough.”

But they didn’t shut up, not in August 1990 when the director of public prosecutions decided there should be no criminal prosecutions. Not a month later when Dr Stefan Popper, the coroner at the first inquest, insisted the jury should consider only events before 3.15pm on the day of the disaster.

The families said this prevented proper discussion of a chaotic medical response that saw fans using advertising hoardings as makeshift stretchers while more than 40 ambulances stayed parked up outside the stadium.

Years later, in 2012, the Hillsborough Independent Panel would rule that 41 victims could have survived beyond 3.15pm.

But in March 1991 the first inquest returned a verdict of accidental death, and Trevor Hicks, on behalf the Hillsborough Family Support Group, was left protesting that while the jury was blameless, the verdict was incorrect and “immoral”.

In November 1993 a High Court judge rejected an application from the families of six victims to have the inquest verdict quashed.

By then, the 95 had become the 96. Tony Bland was allowed to die with dignity when his life-supporting treatment was withdrawn in March 1993.

He had been 18 when he went to see Liverpool play Nottingham Forest and suffered injuries that left him in a persistent vegetative state.

For the families of the 96, a change of government seemed to bring a glimmer of hope. It didn’t last long.

Lord Justice Stuart-Smith, asked to conduct a “scrutiny of evidence” by Tony Blair’s government in 1997, arrived to meet bereaved relatives and “jokingly” asked Phil Hammond, whose teenage son Philip had died at Hillsborough, whether some families were going to turn up late, “like Liverpool fans”.

The Appeal Court judge apologised and explained that despite his off-the-cuff quip he was looking at the evidence with an open mind. He eventually concluded there were insufficient grounds for new inquests to be held.

In August 1998 the Hillsborough families attempted a private prosecution of David Duckenfield. But in July 2000 the jury failed to reach a verdict and Mr Justice Hooper ruled out a retrial.

By now, the families were beginning to face a new sort of narrative, one admitting it had been wrong to blame the fans, but insisting it was time to stop talking about Hillsborough.

Nowhere was this more forcefully expressed than in the pages of The Spectator magazine, then edited by Boris Johnson, where an unsigned October 2004 leading article combined Hillsborough and the death of Iraq hostage Ken Bigley to accuse Liverpudlians of wanting to “wallow in victim status”.

The article brought outrage, but little action beyond an apology visit from Mr Johnson.

So in 2009 when Labour minister Andy Burnham went to Liverpool’s Anfield stadium to address the 20th anniversary memorial ceremony, he did so, as he later admitted, half assuming that “potentially this was one of the last times the country was going to focus on Hillsborough … It wasn’t on the [cabinet] agenda and it wasn’t on the government’s radar.”

But then, as the minister spoke, something rather incredible happened. A large section of the crowd refused to listen in respectful silence and drowned him out with a chant of “Justice for the 96”.

The cameras captured the awkwardness of a government minister being forced to stop talking and nod in agreement with those chanting at him. It became a pivotal, if accidental moment in the campaign for justice.

As Burnham now tells it, he insisted on raising Hillsborough at the following day’s cabinet meeting: “From that came all the developments regarding the Hillsborough Independent Panel.”

In James Jones, the panel’s chair and then-Bishop of Liverpool, the families found a man they saw as one of the first people in power to take them seriously.

When the panel delivered its findings in September 2012, three relatives fainted, so overcome were they to hear an official report agreeing with nearly everything they had been saying for the past 23 years.

The report concluded: “There were clear operational failures in response to the disaster, and in its aftermath there were strenuous attempts to deflect the blame on to the fans.”

Now, the establishment listened when Mr Hicks said: “There were two disasters at Hillsborough – one on the day, and one afterwards: a contrived, manipulated, vengeful and spiteful attempt to divert the blame.”

Prime minister David Cameron, on behalf of the government, and perhaps more broadly, the establishment, offered a “profound apology”.

It paved the way for the original inquest verdict to be overturned at the High Court in December 2012.

The move towards criminal prosecutions gained fresh momentum in April 2016 when, after hearing 267 days’ of evidence, the second inquest jury found that the 96 had been unlawfully killed.

It would be naive to think that the narrative around Hillsborough is completely uncontested.

You probably won’t have to search too hard to find the old prejudices against Liverpool fans lurking on social media.

And last August there was renewed controversy when all criminal misconduct charges were dropped against Sir Norman Bettison, who had been at Hillsborough as an off-duty senior officer of South Yorkshire Police.

Sir Norman said he had been “vindicated” by the CPS decision to drop the charges, adding he had been hounded by false allegations that he had tried to blame Liverpool fans for the disaster.

Many Hillsborough families remained furious that he had been allowed to serve as Chief Constable of Merseyside between 1998 and 2005.

A verdict over Mr Duckenfield would probably produce similar divisions of opinion.

But the Hillsborough families will not be underestimated.

After three decades of dogged, bloody-minded campaigning, never again will anyone think it easy to tell them to “shut their prattle”.