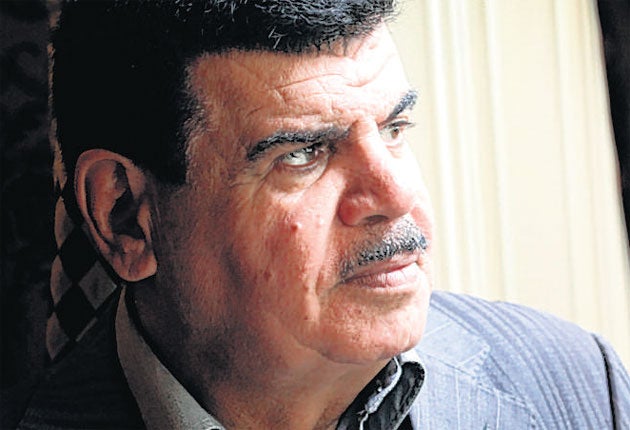

Colonel Daoud Mousa: 'I'm glad troops came to Iraq. But I still weep for the son they killed'

Baha Mousa's father tells Nina Lakhani why he wants to see British soldiers in court

"It's the love for my son that has kept me fighting for justice, not anger at the men responsible for his death," said Colonel Daoud Mousa, the father of the innocent Iraqi man who was beaten to death by British soldiers in Basra.

Colonel Mousa is in London one week after a public inquiry into his son's death identified more than two dozen Army men – soldiers, commanding officers, a doctor and Catholic chaplain – as responsible for the grotesque abuses inflicted on Baha and nine surviving detainees over two days in 2003.

The retired police officer (known to everyone as just Colonel) was singled out by inquiry chairman Sir William Gage as the "driving force" that made the landmark inquiry possible. But even this underplays the determination of a father whose quest for truth and justice made him a fearless campaigner in his fight against the British Government and armed forces.

The colonel, a secular Shia, welcomed the coalition forces into Iraq in April 2003, but six months later his quiet, obedient son was dead. The last time Daoud Mousa saw him alive was on 14 September as soldiers from the 1st Battalion The Queen's Lancashire Regiment raided the Basra hotel where Baha had been working as a receptionist for just 12 days. He had reassured his son the soldiers would return him safely within a couple of hours.

Three days later he was taken to see him in the morgue. "He had a broken nose, a bloody face and a bruised body. He had numerous impact marks on his body as a result of torture," Colonel Mousa recalls. This was never something he could have let go. The tears fall steadily from Colonel Mousa's eyes, reflecting the eight years of unimaginable grief from which he, and his family, will never fully recover. "I cry every time I think about him. We lost our happiness."

Baha's death left his two little boys orphaned as their mother had died after a short illness six months earlier. Hussain, now 14, and Al Hassan, 12, have been raised by their grandparents ever since, who have sought to make their lives normal and happy, "but in the end," he concedes, "we are not their parents. I try to keep them happy but pain isn't something you can easily disguise; they have a cloud of sadness hanging over them."

Hussain, who has clear memories of both his parents, loves to read and wants to come to the UK to study to become an engineer or doctor; Al Hassan wants to be a footballer. Colonel Mousa adds: "When a child wants something, they can command their parents; it is not the same with grandparents. And when a child gets cold in bed in winter, it's their parents they want. They have missed that."

Born in Basra in 1946, he met his first wife, Hadiy, 60, while attending the police academy in the mid 1960s, and they had seven children. He set up a successful import-export business after retiring from the police in 1990. Baha worked in the family business but work dried up after the invasion so he started his job at the hotel.

The first Westerner to believe the colonel's account of what happened was The Independent's Robert Fisk, who knocked on the Mousa family door a few weeks after Baha's death. Fisk's report exposed to the world some of the horrors that went on at the British Army's headquarters in Basra between 14 and 16 September 2003.

Baha's mother has suffered severe depression since her son's death, rarely leaving the house, according to her husband who took a second wife in recent years. He spends a lot of time in Cairo now, driven by a desire to escape memories.

Colonel Mousa is in many ways a broken man. He suffered a stroke and depression following Baha's death, but he remains grateful that Saddam Hussein was overthrown and there is not a trace of bitterness.

While he is satisfied with last week's report, the journey is by no means over. He has instructed his lawyers to ask prosecutors to consider charges against at least 20 men implicated in his son's death for offences ranging from murder to misconduct in public office. "The army have good people and bad people. My anger is towards those who issued the orders and executed the orders. I am still seeking justice. I want those culprits to be tried and take their punishment; that will subdue my pain."