Bullets, prostitutes and ‘mass corruption’: How a tobacco giant’s Mr Fix-It turned whistleblower

Exclusive: Paul Hopkins, the man who used to do British American Tobacco’s dirty work, is now soiling the firm’s reputation

The British American Tobacco (BAT) email was for internal consumption only and never meant for outside eyes. Paul Hopkins is “not your normal run-of-the-mill employee,” a senior company manager wrote, “but then he doesn’t do run-of-the-mill jobs for BAT.”

Run of the mill for Paul Hopkins during his 13-year tenure at BAT involved being shot at, saving the lives of board directors, providing security to VIPs and evacuating employees from war-torn countries.

It also involved fixing “various delicate issues” related to BAT and the tobacco industry. These ranged from unusual “reputational” issues, including retrieving container-loads of cigarettes sold to Iraq in breach of UN sanctions – and obscuring the fact that a BAT finance director, who died in a Nairobi hotel room, had passed away after a drug-fuelled orgy with two prostitutes.

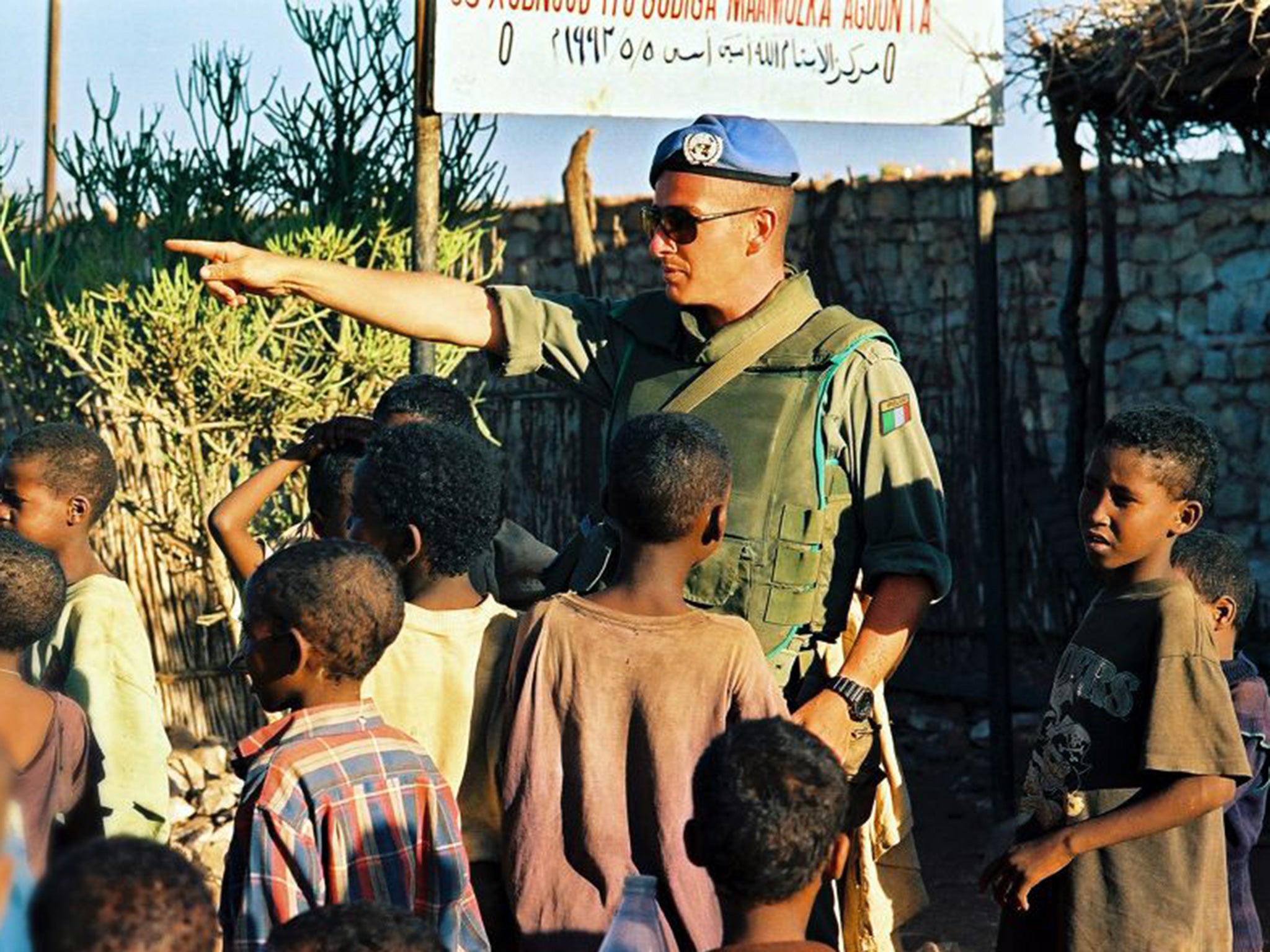

Hopkins took such things in his stride. As a veteran of the Irish Army, including nine in its special forces unit, the Army Ranger Wing, he saw service with UN peacekeepers in Lebanon and Somalia.

What his military career had not prepared him for was the bribery and corruption in the corporate world. When he questioned BAT’s order to “facilitate” payments to law enforcement agents and government officials, he was told it was the “cost of doing business in Africa”.

Such was BAT’s appetite for the fruits of corruption, he became good at it. Documents seen by The Independent show he facilitated payments on BAT’s account to cripple anti-smoking laws in several East African countries, “incentivised” law enforcement to arrest tobacco smugglers, as well as running a sophisticated corporate spying operation involving “black ops” to put rival cigarette-makers out of business.

At BAT’s behest, he cultivated a network of informants in the police and government throughout East and Central Africa, where he headed the AIT (anti-illicit trade) team. Their job was to take out smugglers who were undercutting BAT brands such as Pall Mall, Dunhill and Lucky Strike and 555. Removing smuggled or counterfeit products from the market meant BAT could sell more of its own brands.

At a time when global cigarette sales are forecast to decline, Africa is seen as a place of expansion which tobacco firms are using controversial tactics such as selling single sticks and targeting young people.

He helped secure the arrest of Rwanda’s richest businessman Tribert Rujugiro Ayabatwa in London. Ayabatwa, who heads the cigarette-maker Mastermind, one of Africa’s biggest manufacturers and a major BAT rival, was wanted by the South African tax authorities as well as Interpol. BAT told its teams to close down his operations.

Through his network Hopkins learnt Ayabatwa, wanted for fraud and tax evasion in South Africa, was about to board a UK-bound flight. After a tip-off to Scotland Yard Ayabatwa was arrested. He was later released after agreeing to pay a $7.1m (£4.6m) fine.

As Hopkins’s skills became more widely appreciated he was asked to do more than just combat smuggling. When a senior British-born BAT finance director was found dead in one of Nairobi’s finest hotels after a company conference, Hopkins was asked to deal with the potential “reputational” problems.

These surrounded the fact the executive who was married with two children, had returned to his hotel with drugs and two prostitutes after an evening of clubbing. He ensured the Kenyan police did not charge the sex workers as well as arranging the autopsy report made no mention of the drugs found in the dead executive’s body.

Payments were made in cash through third parties and invoiced back from BAT via two sets of accounts, one for internal use setting out the real details, while a second, sanitised, set referred to fictitious operational spending.

However, a BAT spokesperson said: “All companies in the BAT group are required to operate in line with the group’s standards of business conduct and are obliged to ensure that all 57,000 employees around the world understand them and abide by them.

“Whenever we learn that there is the possibility there may have been a lapse in these standards, our policy is to take all appropriate action. This includes, where relevant, co-operating fully with the authorities. We do not tolerate corruption in our business anywhere in the world.”

The company’s appetite for such methods did not lessen even after the UK’s Bribery Act came into force in 2011. BAT updated its guidelines of the Act’s tough new provisions and sent a summary to employees to sign and return confirming they were aware of the new standards and legal obligations.

Nevertheless, senior managers continued to order him to facilitate payments to achieve BAT’s ends. In recorded conversations with his director Gary Fagan, Hopkins openly reports back on these payments to senior Kenyan Revenue Authority (KRA) officials in return for confidential tax details belonging to a rival cigarette-making firm.

Hopkins would then send the information to Fagan from a bogus email via Fagan’s wife’s email. Fagan, who was BAT’s East and Central Africa’s area director, continues to work for BAT in Africa.

In telephone conversations and emails, Naushad Ramoly, BAT’s regional legal counsel for the region who authorised the payments, never questions Hopkins when he talks about “paying off” people and even takes an active part in one meeting to discuss obtaining a confidential KRA contract. It was when BAT used Hopkins’s carefully built network to enable another department to make bribes that a row resulted and he left the company.

Hopkins was ordered to let the Corporate and Regulatory Affairs (Cora) department use his covert system to make £30,000 payments to “consultants” in Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi and the Comoros Islands. The payments were made but his contractors were alarmed to discover they were directly paying “sitting government ministers or employees in their respective countries”.

“I feel it is crucial that you are aware of the fact that, contrary to Cora’s stating they are purely consultants, they are not,” one warned Hopkins in writing.

In fact they were illegal payments to two members and one former member of the World Health Organisation’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC), a UN initiative aimed at reducing the toll of tobacco-related deaths. BAT paid the insiders to subvert the FCTC proposals before they became law in those countries.

However, when Hopkins raised his concerns internally BAT’s management became silent. He escalated his concerns to London who sent a “whistleblowing” team down to interview him. Despite promises of confidentiality, news of what he had done quickly spread.

The Cora official, who made the payments authorised by her manager, left the company but shortly afterwards Hopkins, after 13 years of service, found himself the subject of a campaign of “harassment”.

His expenses were slow to be paid, his electricity at home cut off after BAT overlooked paying the bill and crucially his work permit was mysteriously delayed and his immigration file vanished.

Colleagues who supported him also suffered. One discovered a promotion he had previously been congratulated on suddenly evaporated. The colleague was later suddenly let go.

Hopkins himself was told he was also under threat of redundancy despite routinely exceeding all his targets. He was placed on gardening leave as rumours circulated he had been sacked.

When Hopkins tried suing BAT for unfair dismissal a London tribunal ruled his contracts, said to be governed by the laws of England and Wales, did not permit him to sue in the UK.

Details of BAT’s bribery first emerged during those hearings. Now Serious Fraud Office officials are examining the allegations it seems likely the secrecy BAT sought to cloak its African operations in may yet be lifted in court.