Alexander Litvinenko: What we now know about the murder of the Russian ex-spy

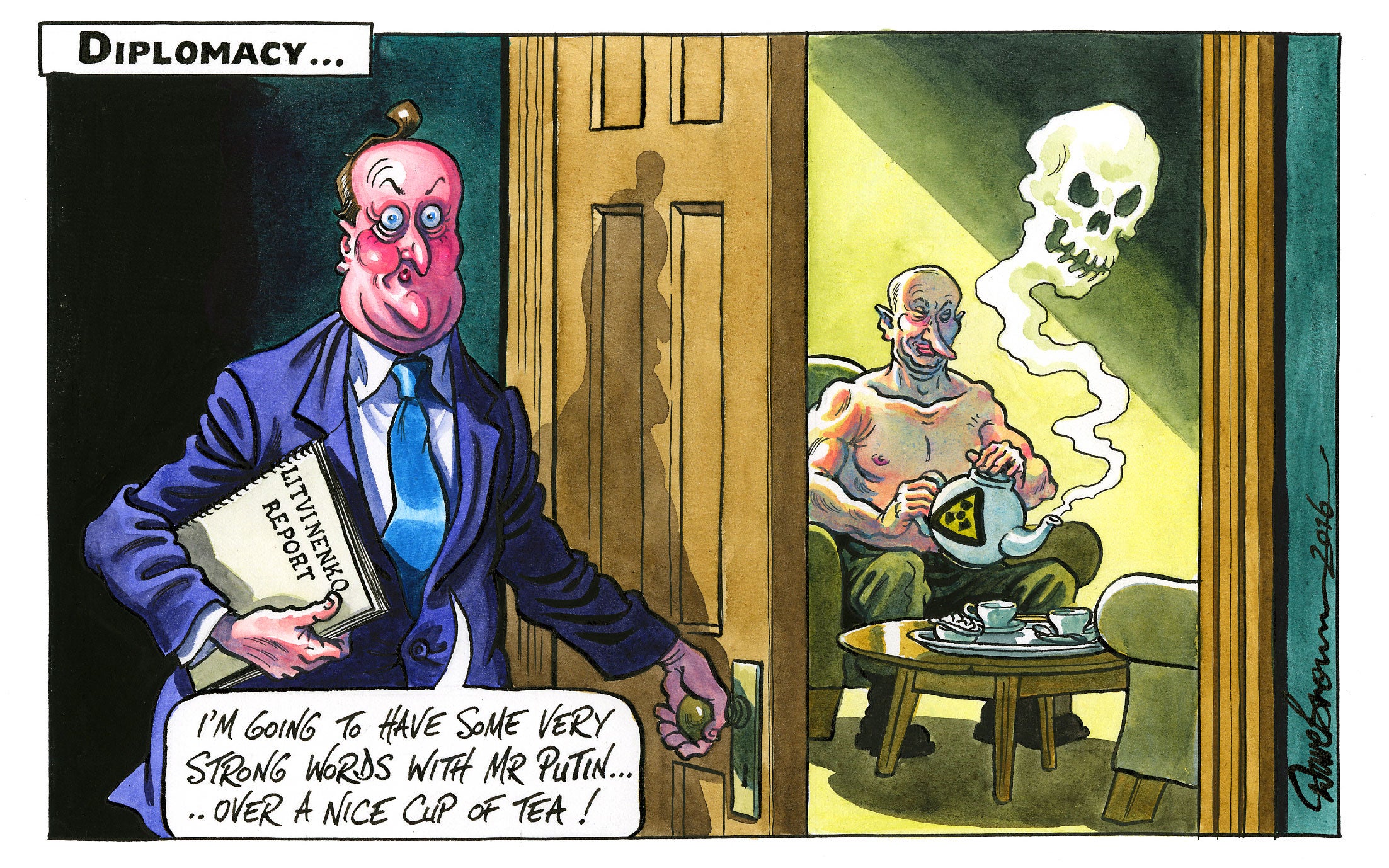

Inquiry’s report details Litvinenko had excited Putin’s ire by calling him a paedophile - and the result was fatal

The murder

Two days before Alexander Litvinenko drank the poisoned half-cup of cold green tea that eventually killed him, one of his named killers was in Hamburg preparing the ground.

Dmitri Kovtun had called a friend – known only as D3 – out of the blue to suggest they meet up so that he could ask for a favour. As they left the upmarket Tarantella restaurant and strolled together to a casino, Kovtun told his friend that he wanted to track down a mutual acquaintance, an Albanian chef, to ask him to put some “very expensive” poison into Mr Litvinenko’s food or drink, according to D3’s later account to police. “Litvinenko was a traitor, there is blood on his hands,” Kovtun allegedly told him.

Two days later, Kovtun flew to London to join Andrei Lugovoi. They met Mr Litvinenko in the Pine Bar at the Millennium Hotel in Mayfair, London. Having failed to secure the services of the Albanian chef, the pair put the polonium 210 in the white porcelain teapot and left it for the teetotal Mr Litvinenko to drink, the chairman of the inquiry concluded.

“I didn’t like it for some reason – well, almost cold tea with no sugar – and I didn’t drink it any more,” Mr Litvinenko told police from his hospital bed. “Maybe in total I swallowed three or four times, I haven’t even finished that cup.”

Kovtun – who later suffered radiation poisoning himself – intimated that he was the tool of higher powers during an apparently unguarded comment to his mother-in-law.

She told police that Kovtun believed he was exposed to the poison which killed Mr Litvinenko. “He said word for word: ‘Those arseholes have probably poisoned us all’,” she later told investigators.

Their potential ignorance of the potency of their choice of murder weapon, polonium 210, may have stemmed from complacency caused by a failed first attempt at killing Mr Litvinenko some two weeks before. Their naivety was also suggested by Lugovoi’s invitation to Mr Litvinenko – having just drunk the radioactive substance – to shake the hand of his eight-year-old son, who had turned up at the end of their meeting.

Why Litvinenko was a target

As both a former agent of a hated state security apparatus and then an arch Kremlin critic, Alexander Litvinenko had collected an impressive number of enemies. In his report, Sir Robert Owen cited five broad themes as to why he would have given the Russian state a reason to murder him.

In 1998, at a press conference in Moscow, he went public with his belief that his employer, the FSB, was a den of corruption. His masters – including the new boss Vladimir Putin – would have considered it an act of betrayal, particularly his claim that he had been ordered to kill a Putin kingmaker turned Kremlin critic, Boris Berezovsky.

Moscow believed that he was working for British intelligence after Mr Litvinenko’s flight to Britain in 2000, where he kept company with fellow enemies of the Russian state, including Mr Berezovsky and Akhmed Zakayev, the exiled Chechen leader.

When he first came to Britain, he was a kept man with the oligarch Mr Berezovsky bankrolling his life, but those funds were being reduced. He was supplementing his income looking into prominent Russians and had embarked on a tentative plan to blackmail Russian “bastards” with links to the Kremlin, the inquiry was told.

Why Putin is in the frame

Sir Robert’s belief that Vladimir Putin “probably” approved the killing stems from personal animosity between the pair and attempts by Mr Litvinenko to expose his former boss’s links to alleged criminality. Their only face-to-face meeting was in 1998, soon after Putin became head of the FSB, when Mr Litvinenko sought his help to expose criminality with the organisation.

While working in a unit that tackled serious organised crime, Mr Litvinenko became convinced of links between a St Petersburg-based criminal group and officials including Mr Putin. Mr Litvinenko’s first impressions were not favourable, he recounted in a book. “I immediately had the impression that he is not sincere,” he wrote of Mr Putin. “He looked not like an FSB director, but a person who played the director.”

A few months later, Mr Litvinenko went public on his claims, which the Russia expert Professor Robert Service said was probably seen by Mr Putin as “the first of a series of occasions on which Mr Litvinenko was guilty of breaching the FSB code of loyalty”.

As a result, Mr Litvinenko was sacked, investigated and jailed, before fleeing with his family to Britain in 2000. From London, and under the protective wing of Mr Berezovsky, he became the most “prominent and ebullient” of critics of the Putin regime. He accused the FSB of co-ordinating a series of apartment bombings, blamed on Chechen separatists, which gave the Kremlin the justification to start a war. Mr Putin was then the Prime Minister.

Mr Litvinenko reached a “climax of attacks” when he described Mr Putin as a paedophile in an article in 2006. Mr Litvinenko claimed that on becoming FSB chief Mr Putin had hunted for any evidence held by the security service of his liking for children, and found video tapes in the FSB vaults which showed him having sex with boys.

Only days before his death, Mr Litvinenko accused Mr Putin, now the President, of responsibility for the murder of the investigative journalist Anna Politkovskaya.

The inquiry heard that as part of his work for private investigation companies in the UK, he drew up a dossier which claimed that a corrupt FSB man was a protégé of Mr Putin. He went on to implicate Mr Putin directly in organised crime, and suggested that he had been involved in helping a Colombian drugs cartel to launder money. That explosive report was passed to a fellow Russian and friend working in the same industry – Andrei Lugovoi – who was later named as his killer and may have passed the document back to the Kremlin.

There is no smoking gun contained within the 328-page report that links Mr Putin directly to the ordering of the killing. But the conclusions of the report are based in part on intelligence reports and witness statements that cannot be released because of national security issues.

The stymied investigation

The extensive inquiry into the murder of Mr Litvinenko was completed despite the “stupid, petty obstructions” put in the way of British police officers who went to Moscow to interview the two main suspects, according to lawyers for the police.

Two Scotland Yard officers, who had travelled to Russia to interview Kovtun and Lugovoi, gave evidence to the inquiry. They complained that when they were being taken to one interview, the Russian car they were following drove so fast and erratically that they thought it was deliberately trying to lose them.

They had to provide questions in advance, were not allowed to make their own recordings in the interviews, and when these did take place they were so rushed that they barely had the opportunity to ask any questions, they said.

When tapes of the interview handed over by the Russians were examined back in London, they discovered that there was not one of the Lugovoi interview. The report also found that the inquiry team was frustrated in attempts to test two commercial aircraft for radioactivity after they had been used by the suspected killers.

Police believe their requests were deliberately frustrated by the Russian authorities. They never had the opportunity to test the aeroplane used by Kovtun and Lugovoi for the first attempt at poisoning some two weeks before the fatal attack.

The Russian refusal to extradite the pair was not considered as part of an attempted cover-up. They never extradite anyone – and given Britain’s unwillingness to send back Boris Berezovsky to Russia it was always unlikely.

What we learnt: Other findings

A startling example of the extent that Mr Litvinenko had become an enemy of the state was highlighted by video evidence of Russian soldiers using targets featuring his face. Police believe his image was plastered on targets at a special forces training centre, where Mr Litvinenko had been a member before joining the FSB. His widow told the inquiry that it had been going on before his death.

The murder weapon – polonium 210 – would have cost tens of millions of pounds, the inquiry was told. Experts pointed to the likely source being a closed nuclear facility, 450 miles from Moscow, both suggesting the likelihood of state involvement. Sir Robert said he could not conclude it was manufactured in Russia.

Andrei Lugovoi sent a T-shirt to Boris Berezovsky with the message “CSKA Moscow Nuclear Death is Knocking Your Door” in what the inquiry found was a “gleeful acknowledgement” of his part in the death.

The writing on the front – “Polonium-210 CSKA London, Hamburg To Be Continued” – was a clear reference to Mr Litvinenko’s murder. Lugovoi had given it to a Russian going to Britain, and asked that it be delivered to the oligarch.

“The T-shirt could be seen as an admission by Mr Lugovoi that he had poisoned Mr Litvinenko, made at a time when he was confident that he would never be extradited from Russia, and wished to taunt Mr Berezovsky with that fact,” said Sir Robert.

Sir Robert said that at the very least it demonstrated approval of the killing by Lugovoi, a fan of CSKA Moscow football club. After the killing, Lugovoi went with his family to see his team play Arsenal in London.