Alexander Litvinenko murder inquiry: Suspect Dimitry Kovtun unsure over whether to give evidence

Dimitry Kovtun may have had late change of heart over testifying to inquiry, reports Mary Dejevsky

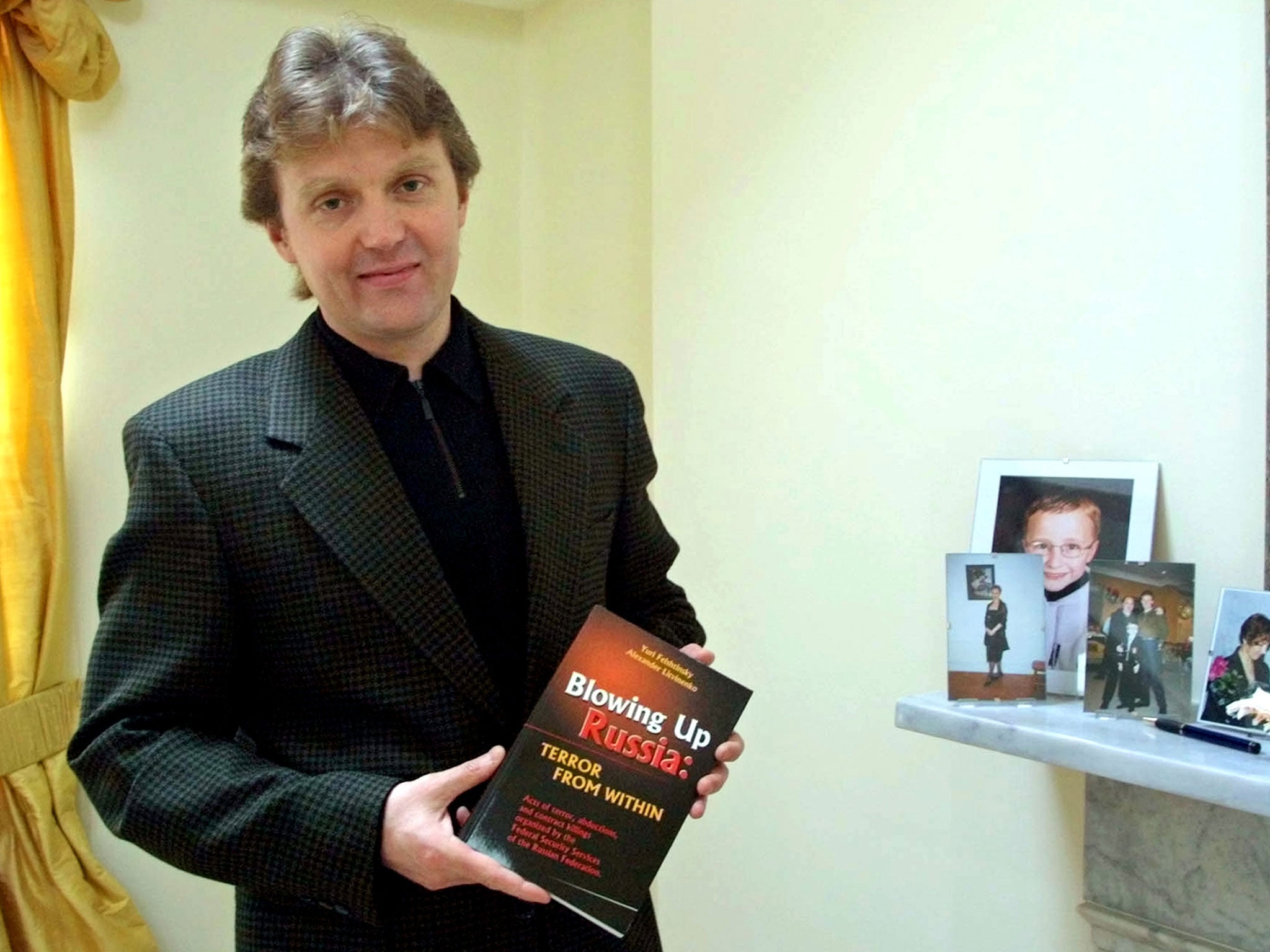

Dmitry Kovtun, one of the two Russians accused of killing Alexander Litvinenko with radioactive poison in London eight years ago, may be about to reverse his 11th-hour decision to give evidence to the inquiry at the Royal Courts of Justice .

Four months almost to the day after throwing the inquiry timetable into disarray by suddenly communicating through intermediaries that he wanted to testify, Kovtun created havoc all over again by sending word that he might not be prepared to give evidence after all.

The Russian government, which had declined an invitation to take part in the inquiry, also effectively withdrew even the limited cooperation it had given in the early stages of the Metropolitan Police’s investigation.

In a response sent 10 days ago, it was revealed that Moscow has said that it wants to exercise its right to have statements and other documents supplied by the Russian police excluded from evidence to the inquiry.

The judge, Sir Robert Owen, said he had little choice but to agree, or risk jeopardising agreements on international police cooperation.

When the inquiry resumed, having being adjourned in March to accommodate Kovtun’s application, the scene was set for three days of high drama in the coming week.

Arrangements were in place for the Russian to testify via video-link from Moscow, starting at 9am on Monday morning. The link had been arranged through a commercial company, to circumvent official the Russians’ non-cooperation.

The inquiry will now reconvene at midday on 27 July. The video-link will be retained, but there is now profound scepticism about whether Kovtun will turn up.

He informed the inquiry by email that he needed clearance from the Russian authorities to testify, and that he could expose himself to prosecution in Russia if he gave evidence without that. The inquiry judge, Sir Robert Owen, and counsel for Litvinenko’s widow, Marina, suggested along with other participants that they were not holding their breath.

All of this casts doubt on why Kovtun ever asked to give evidence. One theory being debated last night was that his last-minute application was always intended as a provocation, designed to sow chaos and confusion in an inquiry that was not going Moscow’s way.

As part of his request, he had also asked for, and been granted, the status of a “core participant”, which entitles him to legal representation at the inquiry and access to all documents. It was speculated on 24 July that his offer to testify had been a ploy to give Moscow access to this.

Richard Horwell QC, for the Met, said: “None of this comes as any surprise. It appears that Kovtun’s request to give evidence was nothing more than an attempt to become a core participant and obtain as much information about these proceedings as he could.”

Given that his initial approaches were through intermediaries, however, it is also possible that Kovtun was acting on his own volition, in a genuine effort to clear his name, or out of pique. While his co-accused, the former KGB agent Andrei Lugovoy, has been feted by the Russian authorities and given a parliamentary seat that affords immunity from prosecution, Kovtun is not reported to have received any honours, and was in hospital for a while suffering from radiation poisoning.

In this event, it would appear that the Russian authorities got cold feet and, decided, at a typically late stage, to put the heavy hand on Kovtun, and threaten him with legal action (for preparing to divulge confidential information). Clearance could yet be granted – this is why Sir Robert Owen, though clearly infuriated by the latest turn of events, has delayed the opening of proceedings on 27 July in the hope of clarity from Moscow. But then it has to be asked under what conditions Kovtun would be testifying, and what price the veracity of anything he said.

Robin Tam QC, counsel to the inquiry, said: “We may have to wait until Monday morning to find if Kovtun is able and willing to give evidence at that time – or we could say, enough is enough, and cancel that.”

The discrediting of Kovtun, which is effectively what has happened, for whatever reason, is likely to leave the inquiry without the answers to the questions that perhaps only he, and Andrei Lugovoi, can answer. One mystery barely touched on in the proceedings is how the polonium-210 that killed Litvinenko was brought to the UK.

Did Kovtun – who was himself contaminated – have anything to do with this, and if he did, was he aware that he was carrying a lethal substance? If he was, did he intend to use it to kill an enemy of the Kremlin (as Litvinenko was by then), or might there have been some other purpose, such as for use as a sample in some illicit trade?

According to one witness, codenamed D2, Kovtun had turned up out of the blue en route to London and vouchsafed to him that he regarded Litvinenko as a “traitor” who had “blood on his hands”.

Kovtun, said D2, then said that he wanted to find a compliant chef in a London restaurant who would be prepared to put some “very expensive poison” in Litvinenko’s food. D3 said he had dismissed Kovtun’s words as just another of his fantastic ideas – until he saw reports of Litvinenko’s death in the papers.

Kovtun: A life in the shadows

Dmitry Vladimirovich Kovtun was born in 1965 into an army family and attended a military academy in Moscow.

Although he is often described as a former KGB officer turned businessman, much about his past is murky.

He moved to Germany in the late 1990s, and told colleagues at the Hamburg restaurant where he worked for a while that he had deserted from the Russian army. They said he was always short of money and full of ideas for business ventures that never came off, though some said he was also brilliant with computers.

He returned to Moscow in the early 2000s, working in the private security sector.

Mary Dejevsky