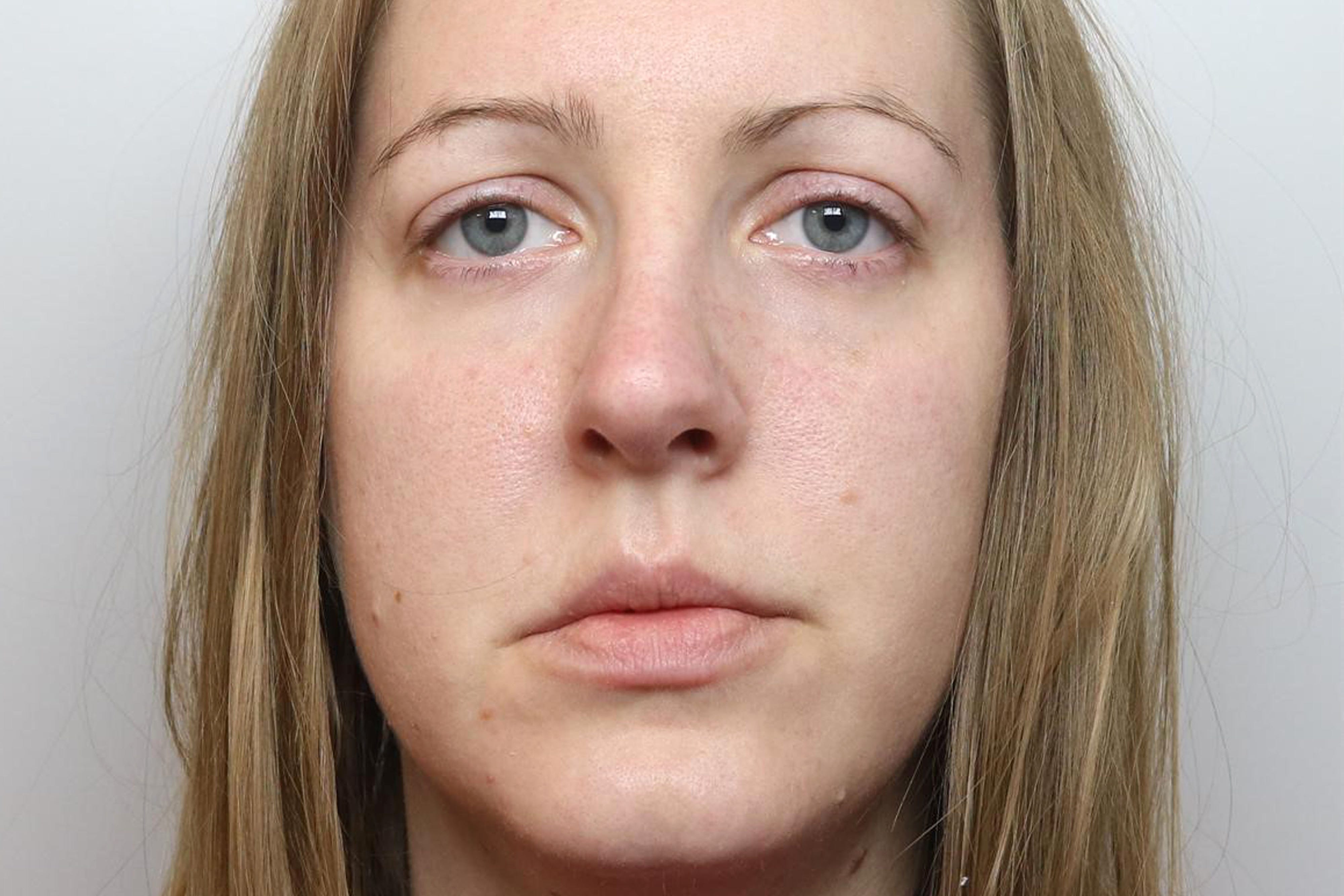

‘Five basic failures’ at hospital where Lucy Letby worked, inquiry told

The Thirlwall Inquiry is examining how the nurse was able to carry out her crimes in the neonatal unit of the Countess of Chester Hospital.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Basic failures by the hospital where killer nurse Lucy Letby worked had “fatal consequences” for babies, an inquiry into her crimes has heard.

On the third day of the Thirlwall Inquiry, set up to examine how the 34-year-old nurse was able to carry out her crimes in the neonatal unit of the Countess of Chester Hospital in 2015 and 2016, an opening statement was given by Peter Skelton KC, representing seven of the families.

He said there were “five basic failures which occurred right from the start and which continued for the next two years”.

Speaking at Liverpool Town Hall on Thursday, Mr Skelton said: “The first failure was to conduct swift, careful and methodical investigations into why each of the deaths occurred and whether there were connections between the deaths.”

He added: “That was a major and catastrophic failure.”

Mr Skelton said it meant vital information was overlooked, with “fatal consequences” for other children.

He said the cluster of deaths and collapses should have been escalated to senior management within the hospital trust immediately, so they could have overseen investigations.

Mr Skelton said: “From the outset, and without prejudice and without pre-judgment, it should have been in the minds of those conducting and overseeing the investigations that the cluster of unexpected and unexplained deaths might have been caused by the criminal acts of a member of hospital staff.”

The barrister said a report into Beverley Allitt, a nurse who killed children at Grantham Hospital, Lincolnshire, in 1991, sought to ensure that healthcare staff were prepared to keep their minds open to the possibility of criminal conduct.

As well as the Allitt case, Mr Skelton said that in May 2015, just before Letby’s crimes began, nurse Victorino Chua was sentenced for murdering patients at Stepping Hill Hospital.

He said: “It is difficult to understand why events at Stepping Hill did not at the very least alert those at the Countess of Chester from the start that the cluster of unexpected deaths were the result of potential criminality and that active steps were required to rule out that possibility.”

Mr Skelton said the police and coroner should have been informed at the outset, which could have had a “profound effect” on the course of events.

He told the inquiry the fifth failure was not to inform the families that the deaths were being investigated with a view to finding out why they occurred.

Mr Skelton said: “You will hear from some of the parents over the next few weeks about how they were kept in the dark about the collapses of the babies and the concerns and investigations that were being undertaken into their babies’ deaths.”

He said the failings were made “all the more indefensible” by the increase in numbers of neonatal deaths.

A “major opportunity” to identify criminality was missed by medics in August 2015 when a child’s abnormal blood test result revealed raised levels of insulin, he said.

As paediatricians began to suspect in late 2015 that Letby was the direct cause of deaths and her actions may have been deliberation, Mr Skelton said the suspension of Letby from nursing duties and contact with the police should have followed.

Safeguarding and whistleblowing procedures should have also have taken place at that point as well an approach to affected parents to fully appraise them of what may have happened to their children, he added.

Instead what happened was “denial, deflection and delay on the part of the hospital executives, the inquiry heard.

Mr Skelton said the consultants who flagged concerns about Letby “deserved the gratitude” of the families and had acted with “tenacity” and “courage” in “genuine fear of adverse professional consequences”.

But he said they should have outlined their concerns clearly and formally in writing and ensured they were brought to the attention of the management and the board.

And should have spoken to the police if they were not satisfied, he said.

Mr Skelton said there were “growing schisms between the doctors and the nurses, and the doctors and managers” which led to an “apparent lack of perspective” which was need to protect babies from a “ruthless and determined serial killer”.

Mr Skelton said it seemed the hospital’s then medical director Ian Harvey does not accept he should have told the police sooner about Letby, or accept personal responsibility that she was caught sooner.

He said: “It was not for Mr Harvey to assess the validity of the concerns.

“The consultants were treated by him as a problem that would not shut up and go away.

“Over time an upside down situation evolved in which the consultant’s suspicions were never satisfactorily relayed.”

Richard Baker KC, representing other families, said the convictions and the indictments against Letby “did not tell the full story”.

A jury found Letby guilty of attempting to murder Child K, a baby girl, by deliberately dislodging her breathing tube in February 2016. The infant was transferred to a different hospital days later where she died.

Mr Baker said Child K’s parents believe “with justification” that she was murdered by the nurse.

A verdict could not be reached on an alleged attack in November 2015 on another baby girl, Child J, who survived, but Mr Baker said her parents too had “no doubt” that Letby caused the collapse.

He said they also thought their daughter was targeted the following month, although Letby was never charged over that incident.

Mr Baker told Lady Justice Thirlwall that collapses in neonatal units such as dislodgement of endotracheal tubes was “uncommon”.

He said: “It generally occurs in less than 1% of shifts.

“You will hear that an audit carried out by Liverpool Women’s Hospital recorded that whilst Lucy Letby was working there dislodgement of endotracheal tubes occurred in 40% of shifts that she worked.

“One may wonder why?”

The killer nurse completed two work placements at Liverpool Women’s Hospital in 2012 and 2015.

Letby, from Hereford, is serving 15 whole-life orders after she was convicted at Manchester Crown Court of murdering seven infants and attempting to murder seven others, with two attempts on one of her victims, between June 2015 and June 2016.

The inquiry, chaired by Lady Justice Thirlwall, is expected to sit until early 2025, with findings published by late autumn of that year.

A court order prohibits reporting of the identities of the surviving and dead children involved in the case.