Rare and dazzling cosmic explosion spotted by researchers

The explosion, which outshines most supernovae in the universe, was spotted by researchers at the Queen’s University, Belfast.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A rare and dazzling cosmic explosion, which outshines most supernovae in the universe, has been spotted by researchers at Queen’s University, Belfast.

The unusual new blast analysed by researchers is as bright as hundreds of billions of suns, but unusually it lasts less than half as long as typical supernova.

In a newly published study, the researchers first identified the event using the Atlas network of robotic telescopes.

The telescopes in Hawaii, Chile and South Africa scan the entire visible sky every night to search for any object that moves or changes in brightness.

These galaxies contain billions of stars like our sun, but they shouldn’t have any stars big enough to end up as a supernova

Within days of detecting the explosion – named AT2022aedm – the researchers obtained more data with the New Technology Telescope in Chile and found that it looked unlike any known supernova.

Follow-up data from observatories around the world showed that the explosion faded and cooled down much faster than expected.

Dr Matt Nicholl, from the School of Mathematics and Physics at Queen’s, said they have been hunting for the most powerful cosmic explosions for over a decade, adding “this is one of the brightest we’ve ever seen”.

“Usually, with a very luminous supernova, it will have faded to maybe half of its peak brightness within a month. In the same amount of time, AT2022aedm faded to less than one per cent of its peak – it basically disappeared,” he said.

The location of the explosion was also described as a surprise.

Dr Shubham Srivastav, also from Queen’s, added “Our data showed that this event happened in a massive, red galaxy two billion light years away. These galaxies contain billions of stars like our sun, but they shouldn’t have any stars big enough to end up as a supernova.”

The team searched through historical data and found just two other cosmic events with a similar set of properties.

These were discovered by the ROTSE and ZTF surveys in 2009 and 2020. The extensive data set obtained for AT2022aedm shows that these are a new type of cosmic events.

Dr Nicholl added: “We have named this new class of sources ‘Luminous Fast Coolers’, or LFCs. This is partly to do with how bright they are and how fast they fade and cool.

“But it’s also partly because myself and some of the other researchers are huge fans of Liverpool Football Club. It’s a nice coincidence that our LFCs seem to prefer red galaxies.”

Dr Nicholl said that the discovery has opened up avenues for more research.

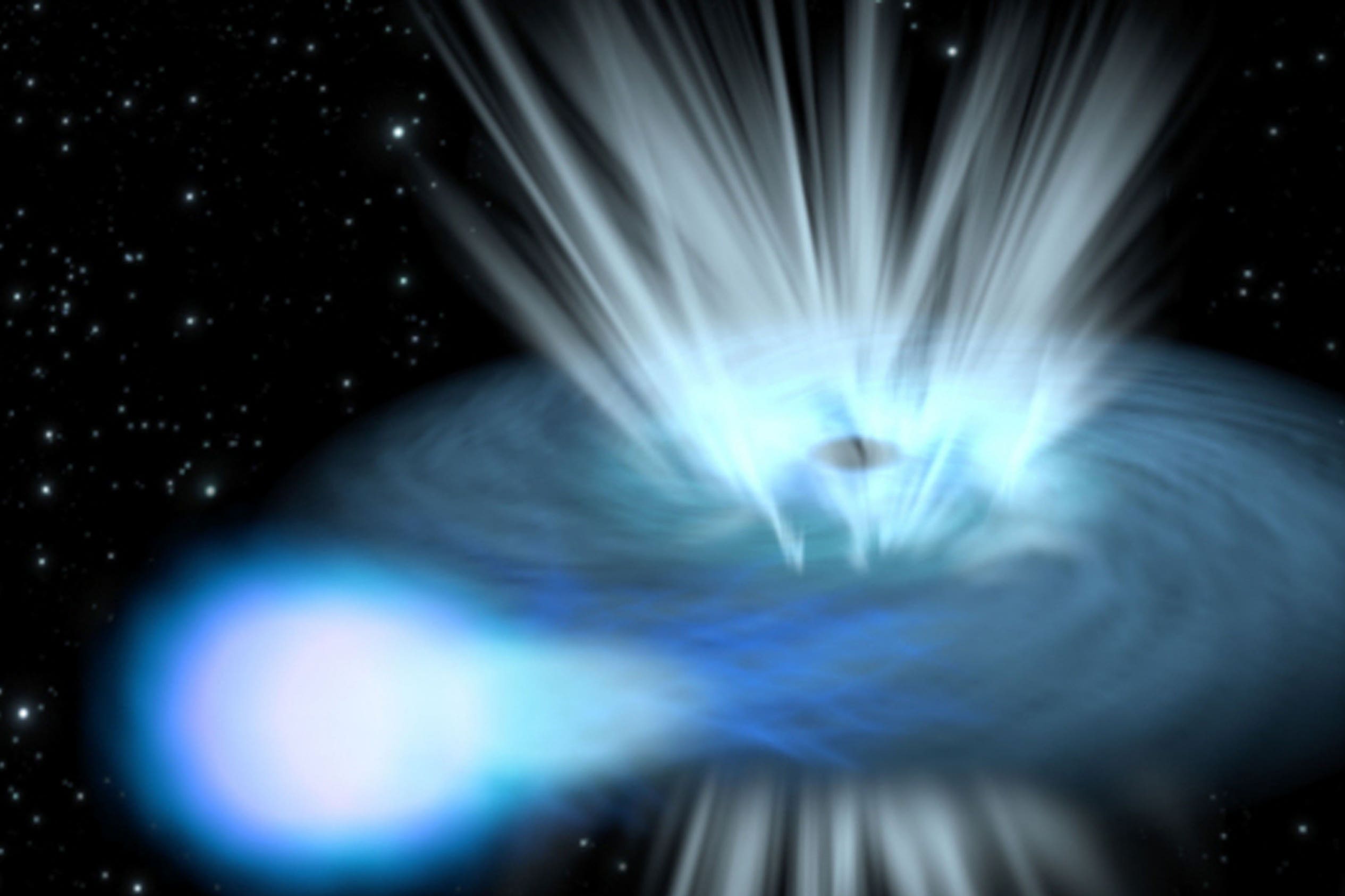

“The exquisite data set that we have obtained rules out this being another supernova. The most plausible explanation seems to be a black hole colliding with a star,” he said,

“If we find more LFCs, especially in the more local Universe, we should be able to test this scenario. Collisions are more likely in dense star clusters, so we can look for these at the sites of the explosions.”

The research paper has been published in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.