Why are teenagers so moody?

Many stereotypical adolescent behaviours have clear explanations in science

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The volatile nature of teenagers' emotions is as well documented as it is familiar to most parents.

Research indicates that a succession of hormonal changes in the brain during puberty makes teenagers far more likely to display such behaviour.

The changes start when the hypothalamus releases a protein called kisspeptin, which triggers the pituitary gland to release testosterone, estrogen and progesterone – the hormones that stimulate the changes we recognise in puberty.

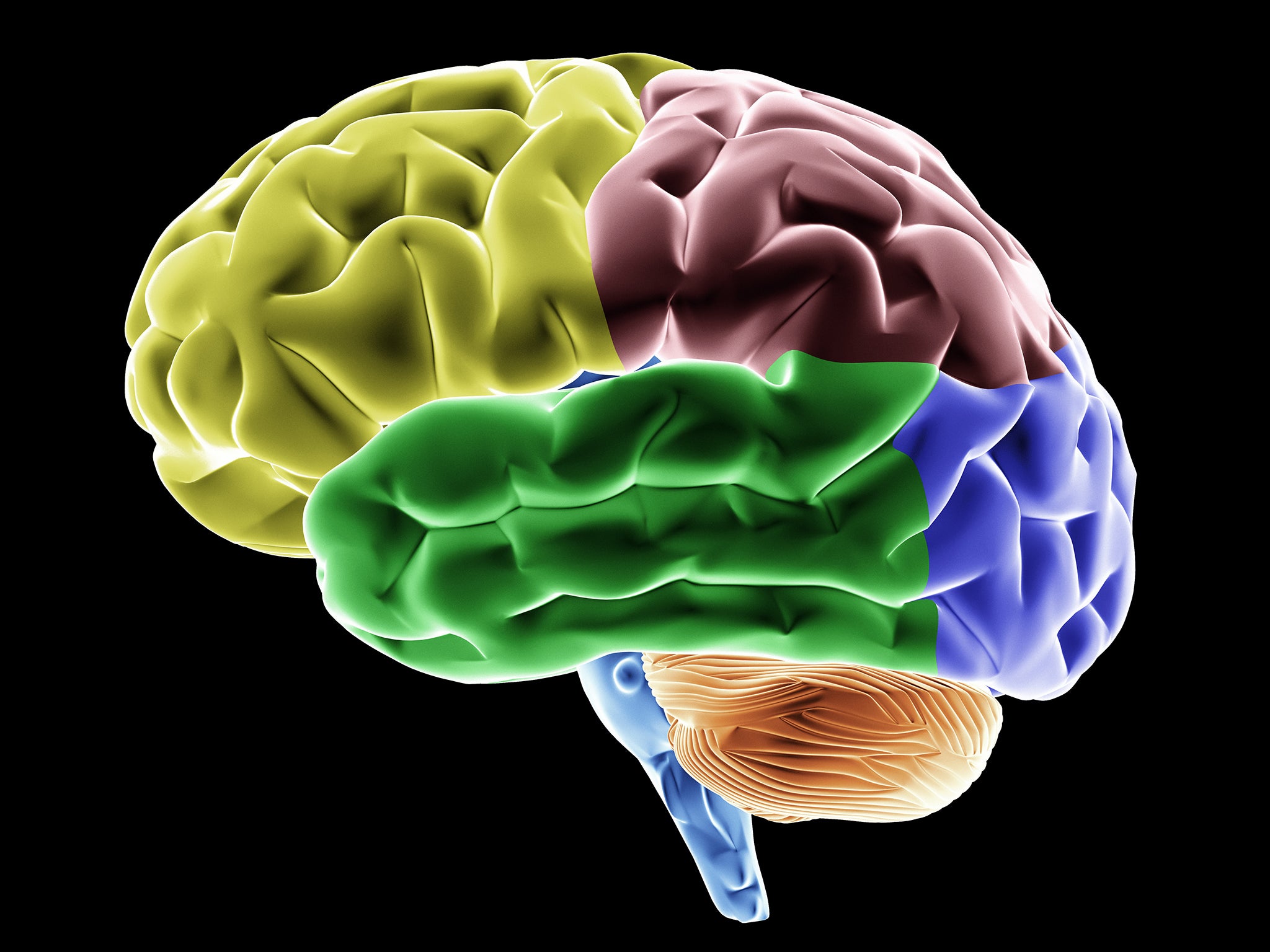

As well as development in the body – the formation of breasts, testes and so on – a lot of less obvious changes are taking place in the brain.

The high levels of testosterone, estrogen and progesterone during puberty can cause a person to react more strongly to emotionally loaded content - like a sad song, for example.

It also explains why teenagers are more likely to run into problems at school and social lives.

Heightened levels of these hormones in the brain can also make a person more likely to take risks, which is why teenagers sometimes engage in more dangerous and risky behaviours than adults.

In addition, the prefrontal cortex – the part of the brain that controls risk assessment and planning ahead – is not fully developed yet in the teenage years.

This means that the part of their brain that is supposed to stop them acting on this attraction is not up to the job.

Teenagers also put far more value in peer acceptance than adults do – not being accepted among other people their age can call them to have intense feelings of unworthiness and anxiety.

Scientists have pinpointed an evolutionary reason for this – it is important for adolescents to engage with people other than their family after reaching sexual maturity in order to reduce inbreeding and encourage genetic diversity.

This might explain why a child who is very close to his or her mother will suddenly appear to have no interest in her anymore, and "replace" her with a friend.

Teenagers are also prone to higher levels of anxiety – and they’re not just being dramatic. In adults and children, the hormone allopregnanolone released in the brain in times of stress will calm us down. However, hormone changes during puberty mean that allopregnanolone can actually have the opposite effect in teenagers, leaving them prone to heightened anxiety.

The hormone is typically released in times of stress, which means that a love level stressful situation like having a big pile of homework can cause a teenager to become extremely anxious, panicked or depressed.

Circadian rhythms, which control our sleep patterns, also change during puberty. A teenager’s sleep pattern is likely to be set back a few hours, making them more likely to stay up late and sleep in late.

Given that they’re dealing with change in sleeping pattern, heightened anxiety, a propensity to respond emotionally and a desperation to be recognised by peers it is unsurprising that teens appear to be moody and disagreeable – it actually seems like they might be coping rather well.

Thankfully, being a teenager does not have to be all bad.

The teenage years are a time when we are most able to adapt and take in new information, which is why they can immediately understand how to use the newest iPhone while you struggle to work out how to install Emoji. It’s also why teenagers can learn 16 maths equations in a night and memorise endless pop song lyrics.

They also have a heightened ability to read and analyse social cues such as facial expressions, so are more likely to form positive relationships and are better at socialising.

Teenagers can also make many positive changes in their lives if they wish to do so: risk taking behaviours aren’t always bad, and teens are likely to take lots of positive steps thanks to their fearlessness.

This video from ASAP Science explains further.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments