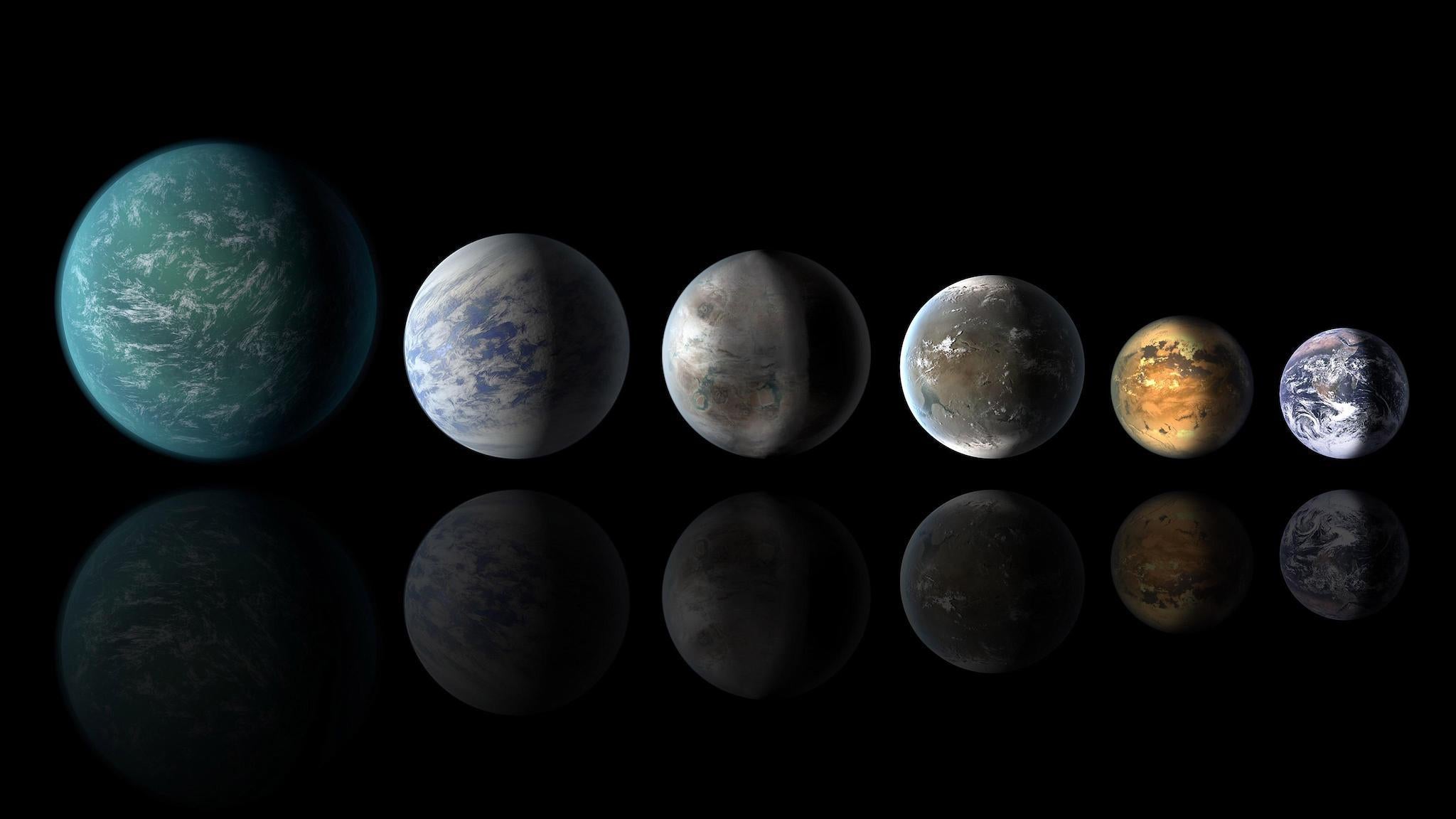

Watery worlds could be common throughout the galaxy – suggesting life could be more likely than we know

Scientists expect to find much more about the strange worlds in the coming years

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Watery worlds could be common throughout the universe, scientists have said in a discovery that could have major effects on the search for life elsewhere in the universe.

Planets covered in large amounts of water could be far more common than we'd previously realised, according to the new study. By exploring the known masses of nearby exoplanets, they found that their sizes could be explained by large amounts of water.

The discovery could suggest that there are many more Earth-like planets with water throughout the galaxy. That, in turn, could suggest there are other planets that are able to support life, just like Earth.

Many of the exoplanets that have been discovered in recent years and have so excited scientists could be as much as 50 per cent water. By comparison, the Earth is only 0.02 per cent water by weight.

"It was a huge surprise to realise that there must be so many water-worlds", said lead researcher Dr Li Zeng from Harvard University.

The worlds themselves might have water, and might even have life. But that doesn't mean they look anything like our home planet, or even a watery version of it.

"This is water, but not as commonly found here on Earth", said Li Zeng. "Their surface temperature is expected to be in the 200 to 500 degree Celsius range. Their surface may be shrouded in a water-vapor-dominated atmosphere, with a liquid water layer underneath.

"Moving deeper, one would expect to find this water transforms into high-pressure ices before we reaching the solid rocky core. The beauty of the model is that it explains just how composition relates to the known facts about these planets".

Previous studies have found that many of the 4,000 confirmed or potential exoplanets fall into one of two sizes: those that are about 1.5 times the radius of the Earth, and others that are roughly 2.5 times the size of our planet.

The new research looks to explore how those planets might be structured on the inside. It found that the smaller of the planets tend to be rocky – but the bigger ones are "probably water worlds", according to the researchers.

Scientists expect to find more of those planets – and therefore more water worlds – in the coming years. Leading that search will be Nasa's TESS mission which will look out for more of the exoplanets, and the James Webb Space Telescope which is due to launch in 2021 and will analyse the atmosphere of those worlds.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments