US military plan to spread viruses using insects could create ‘new class of biological weapon’, scientists warn

Agency says it is trying to genetically modify crops, but experts think this goal is 'simply not plausible'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Insects could be turned into “a new class of biological weapon” using new US military plans, experts have warned.

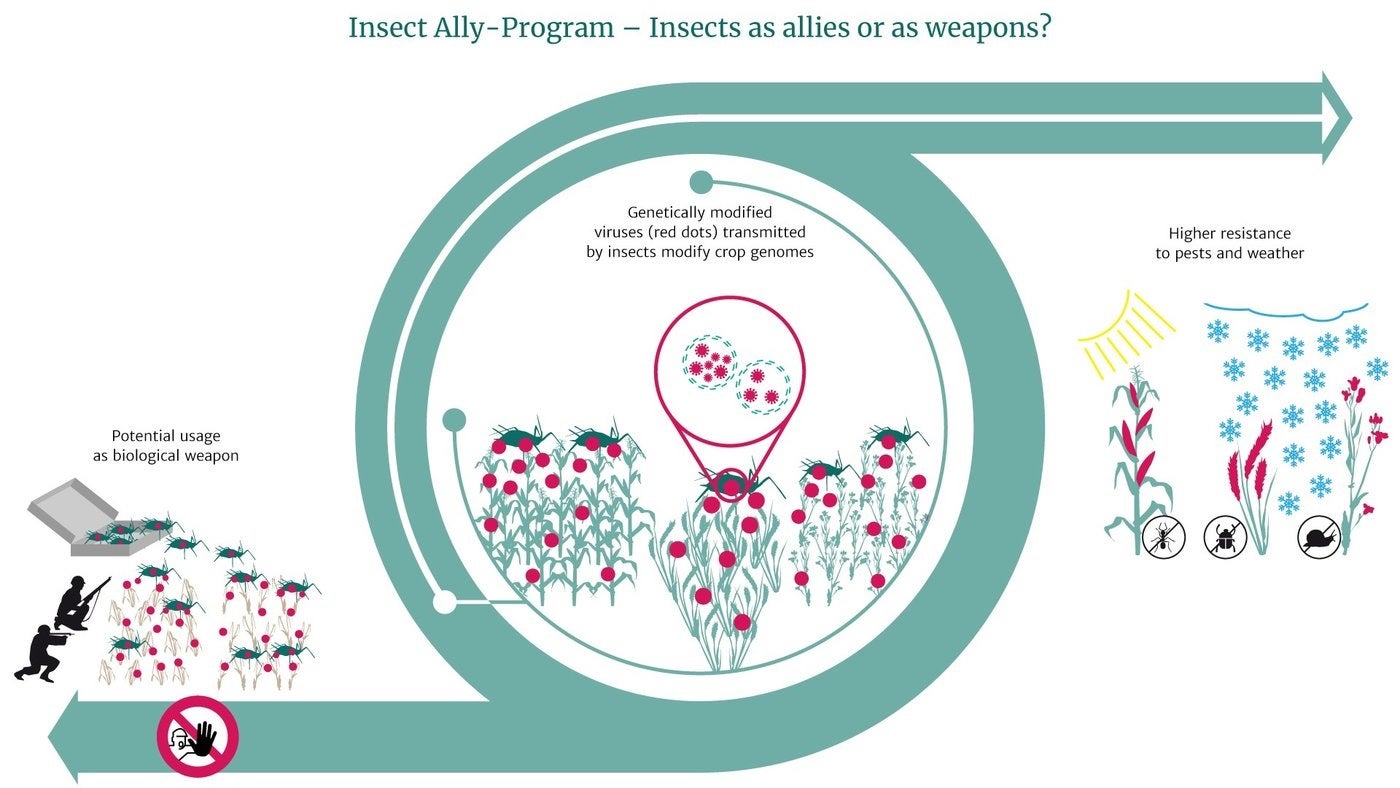

The Insect Allies programme aims to use bugs to disperse genetically modified (GM) viruses to crops.

Such action will have profound consequences and could pose a major threat to global biosecurity, according to a team that includes specialist scientists and lawyers.

However, the Defence Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa), which is responsible for developing military technologies in the US, says it is merely trying to alter crops growing in fields by using viruses to transmit genetic changes to plants.

In theory, this rapid engineering would allow farmers to adapt to changing conditions, for example by inserting drought-resistance genes into corn instead of planting pre-engineered seeds.

But this seemingly inoffensive goal has been slammed by the scientists, who say the plan is simply dangerous and that insects loaded with synthetic viruses will be difficult to control.

They also say that despite being in operation since 2016 and distributing $27m in funds to scientists, Darpa has failed to properly justify the existence of such a programme.

“Given that Darpa is a military agency, we find it surprising that the obvious and concerning dual-use aspects of this research have received so little attention,” Felix Beck, a lawyer at the University of Freiburg, told The Independent.

Dr Guy Reeves, an expert in GM insects at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology, said that there has been hardly any debate about the technology and the programme remains largely unknown “even in expert circles”.

He added that despite the stated aims of the programme, it would be far more straightforward using the technology as a biological weapon than for the routine agricultural use suggested by Darpa.

“It is very much easier to kill or sterilise a plant using gene editing than it is to make it herbicide or insect-resistant,” explains Reeves.

Experiments are reportedly already underway using insects such as aphids and whiteflies to treat corn and tomato plants.

Mr Beck said he and fellow experts were not suggesting that the US military wanted to create biological weapons, but that the proposed agricultural uses are “simply not plausible for a number of reasons”.

Firstly, they note that if farmers wanted to use genetically modified viruses to improve their crops, there is no reason not to use conventional spraying equipment.

They also noted that despite Darpa stating that no insects used should survive longer than two weeks, if such safeguards were not in place “the spread could in principle be unlimited”.

Mr Beck added: “The quite obvious question of whether the viruses selected for development should or should not be capable of plant-to-plant transmission – and plant-to-insect-to-plant transmission – was not addressed in the Darpa work plan at all”.

Making their case in the journal Science, the team noted that if Insect Allies’ research cannot be justified, it could be perceived as breaching the UN’s Biological Weapons Convention.

“Because of the broad ban of the Biological Weapons Convention, any biological research of concern must be plausibly justified as serving peaceful purposes,” explained Professor Silja Voeneky, a specialist in international law at Freiburg University.

“The Insect Allies Program could be seen to violate the Biological Weapons Convention, if the motivations presented by Darpa are not plausible.

“This is particularly true considering this kind of technology could easily be used for biological warfare.”

To prevent any suspicion and to avoid encouraging other nations to develop their own technologies in this area, the authors of the study have called for more transparency from Darpa if it intends to pursue such programmes.

A spokesperson from Darpa defended the programme, explaining that using insects to apply these gene altering treatments could provide advantages over sprays.

“Most importantly in this context, sprayed treatments are impractical for introducing protective traits on a large scale and potentially infeasible if the spraying technology cannot access the necessary plant tissues with specificity, which is a known problem,” they said.

“If Insect Allies succeeds, it will offer a highly specific, efficient, safe, and readily deployed means of introducing transient protective traits into only the plants intended, with minimal infrastructure required.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments