Ukraine crisis in space: America takes on the Russians - over the International Space Station

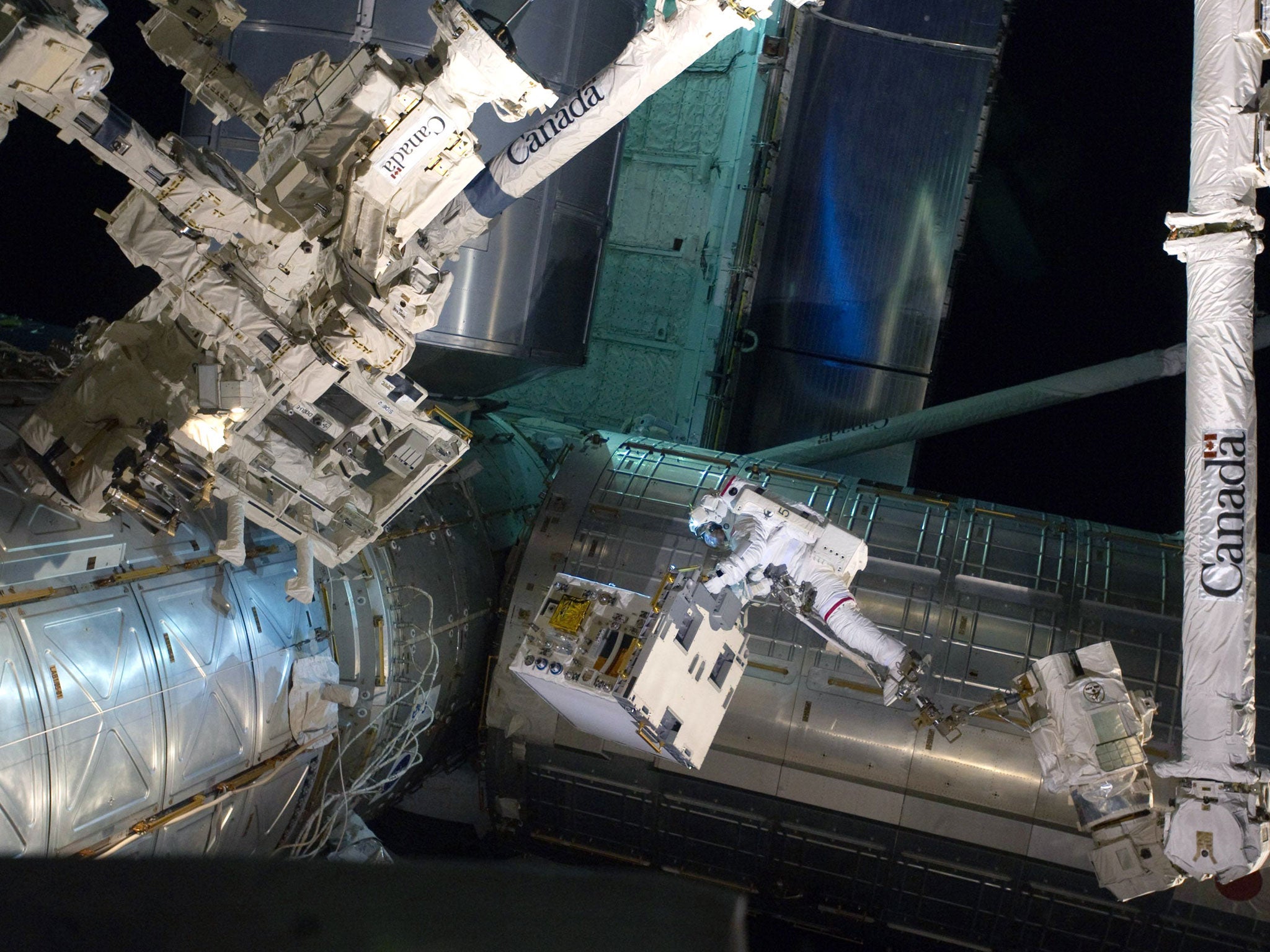

A joint enterprise since the 1990s, the $150bn international research laboratory is still physically divided along Cold War lines

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Even during the paranoia and antagonism of the Cold War, the United States and Russia managed to find common cause in space. In July 1975, both countries celebrated the first joint space flight, as Apollo and Soyuz spacecraft docked in orbit, astronauts and cosmonauts smiling for the cameras as they shook hands through the air lock.

But now the spirit of co-operation appears to have died, with the International Space Station – the $150bn (£89bn) international research laboratory that is still physically divided along Cold War lines – becoming the rope in a tug-of-war between American and Russian politicians.

The dispute began in April, when a leaked Nasa memo revealed that the agency would be suspending all contact with the Russian government because of the country's "ongoing violation of Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity".

Although the involvement of the US government was not explicit, the space agency's decision was widely assumed to have involved the White House and State Department. Subsequent export restrictions – more specifically, "high technology defence articles or services" – confirmed the US's intent to punish Russia's struggling space industry.

However, there's one area where the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, remains king: transport.

After the retirement of the Space Shuttle in 2011, the US was entirely reliant on Russian rockets – specifically Soyuz rockets, descendants of those used in the 1975 mission – to get its astronauts to and from the space station.

Last week, Russia's Deputy Prime Minister, Dmitry Rogozin, said that Moscow was "very concerned about continuing to develop hi-tech projects with such an unreliable partner as the United States", and declared that the country would reject US plans to use the ISS beyond the station's planned "retirement" in 2020.

Mr Rogozin later softened Moscow's stance slightly, saying that the Russians understood that the ISS was "fragile in the literal and figurative sense", and that it would "act very pragmatically and not put obstacles in the way of work on the ISS". But, for America, the incident has highlighted the dependency of its current aerospace programmes.

In addition to paying Russia $71m for the privilege of sending a single astronaut to the ISS, the Pentagon relies solely on Russian-made RD-180 rockets for its launches and the country's current stockpiles – enough for two years – will not be of use if Roscosmos continues to sell engines under the new restrictions: "That they will not be used to launch military satellites."

James Oberg, a former rocket engineer and author of Star-Crossed Orbits, a book about the two country's joint history in space, said that the latest exchange of words marked the end of their "partnership of reluctant co-dependence" and the beginning of a new era for the industry.

"This represents a shift in space operations that has long been gathering force," he said. "We're moving from the Cern model, where everyone builds one thing together, to the Antarctic model, where everyone has their own programme."

Mr Oberg said that the falling entry cost for space launches has encouraged not only new projects from countries such as China and India, but the birth of a new commercial sector, with three main players developing the capacity to deliver crews into orbit. There are long-time US defence contractors Boeing and Sierra Nevada, but also SpaceX, the ambitious start-up created by Elon Musk, the billionaire founder of PayPal.

The Russian threats could prove positive for Nasa as well as the private sector. The agency's chief executive, Charles Bolden, used the threat of limited launches as both stick and carrot to force Congress to accept Barack Obama's proposed $17.5bn budget for 2015, including $848m for the agency's "Commercial Crew" programme. "The choice moving forward is between fully funding the President's request to bring space launches back to American soil or continuing to send millions to the Russians," wrote Mr Bolden in a blog post at the end of March. "It's that simple."

"What Mr Rogozin is doing is strengthening Nasa's hand to accelerate existing programmes for full autonomy," added Mr Oberg. "And when they arrive – the really far-sighted Russians have been telling me – in the next three to five years, the last segment of the space industry where Russia has a powerful role will be closed off to them. They'll be irrelevant."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments