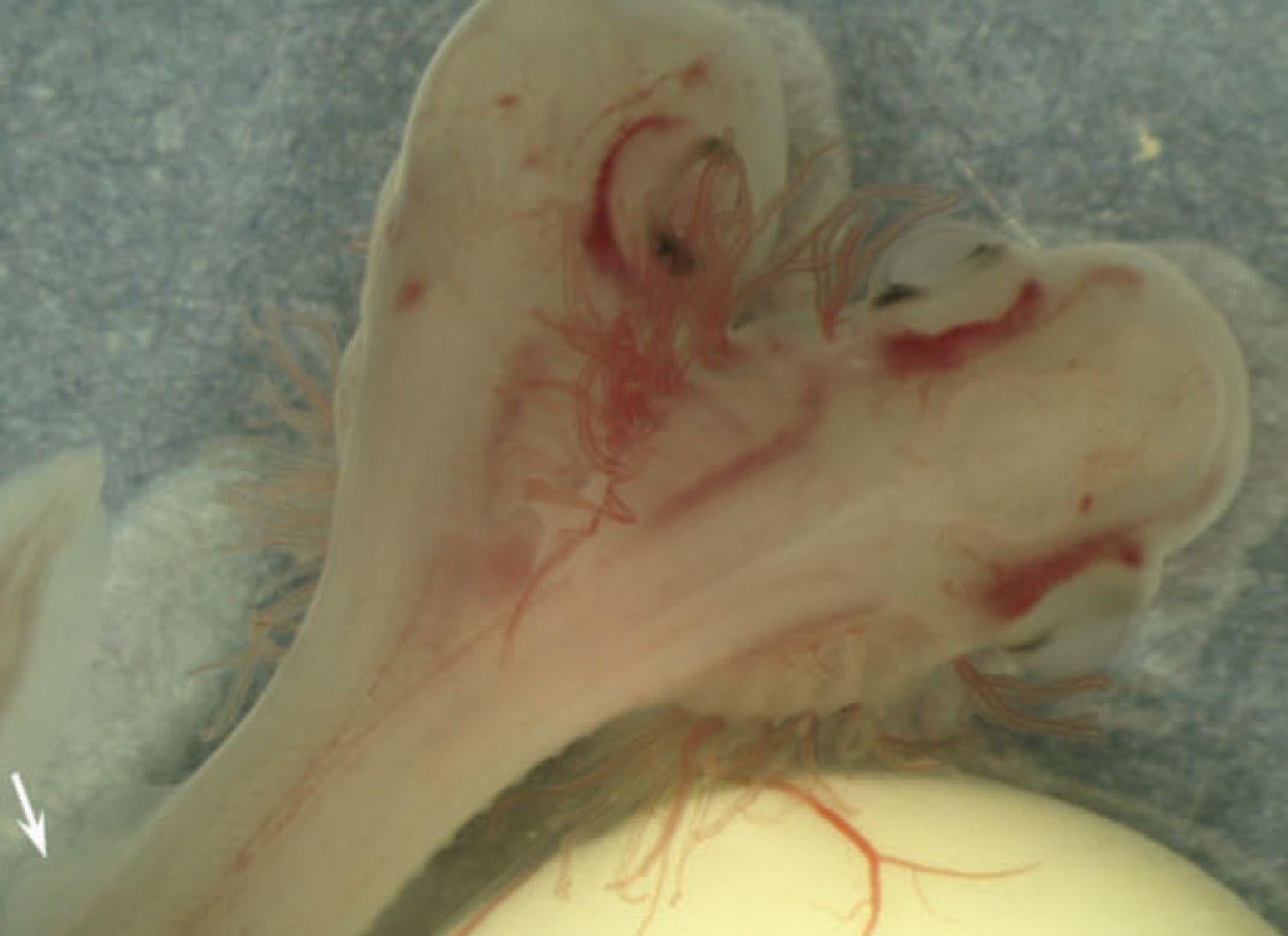

Two-headed sharks are becoming more common and no one knows why

A large reduction of the gene pool caused by overfishing is blamed for the deformity

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.An increasing number of two-headed sharks are being reported in the wild, leaving scientists unable to explain why.

Over the last few years, a growing number of these genetic aberrations have been discovered and examined by scientists.

Professor Valentín Sans Coma, from the University of Malaga, studied the embryo of a two-headed catfish shark in a laboratory condition alongside 800 other shark embryos.

He has claimed a genetic disorder is the most reasonable explanation for the mutation as the unborn fish were not exposed to any infection, chemicals or radiation, reports the National Geographic.

Regarding wild sharks, scientists have blamed the mutation on a cocktail of factors including viral infections, metabolic disorders and pollution.

After studying a two headed smalleye smooth-hound shark and a two-headed blue shark, marine scientist Nicolas Ehemann claimed overfishing was probably to blame.

She explained overfishing had massively reduced the fish gene pool, making genetic disorders such as having two heads more common.

The issue facing scientists looking to study this phenomenon is that two-headed sharks generally do not live long.

Professor Ehemann said: "I would like to study these things, but it's not like you throw out a net and you catch two-headed sharks every so often. It's random."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments