Rates of syphilis around the world mapped by scientists

The development of penicillin saw cases of the disease plummet, but some places proved 'more resilient' than others

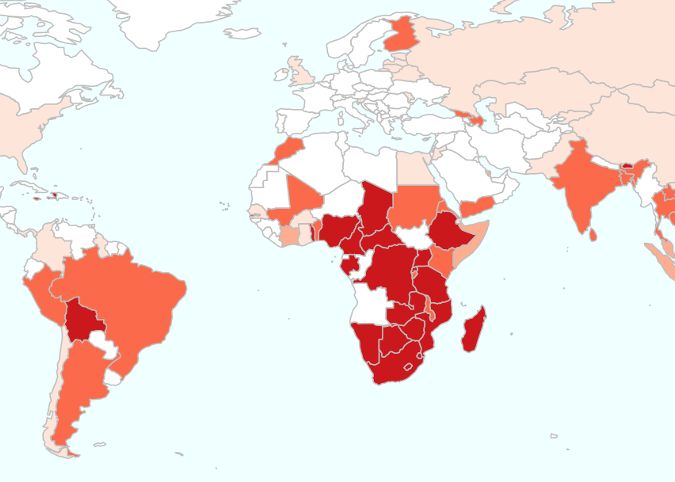

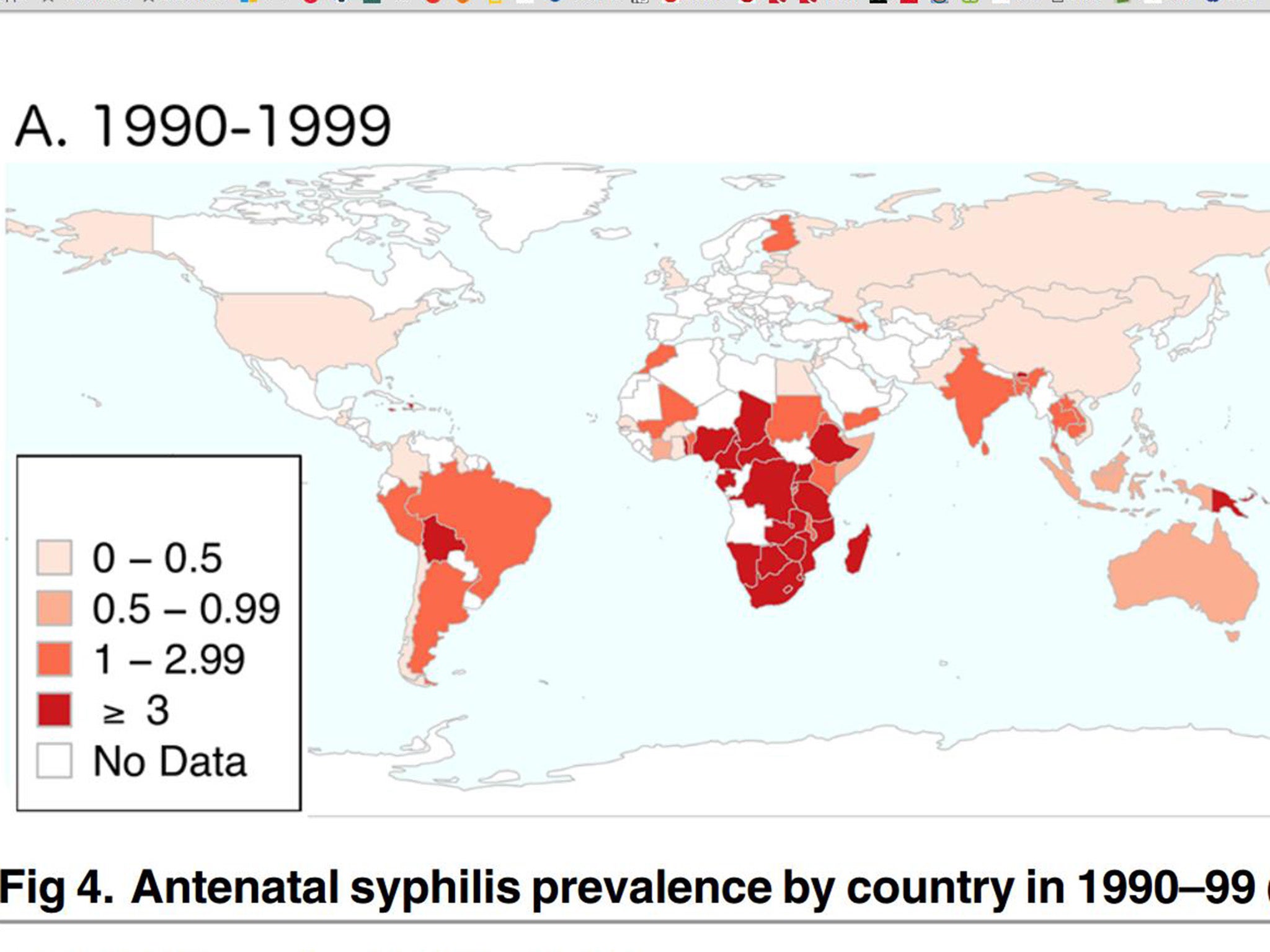

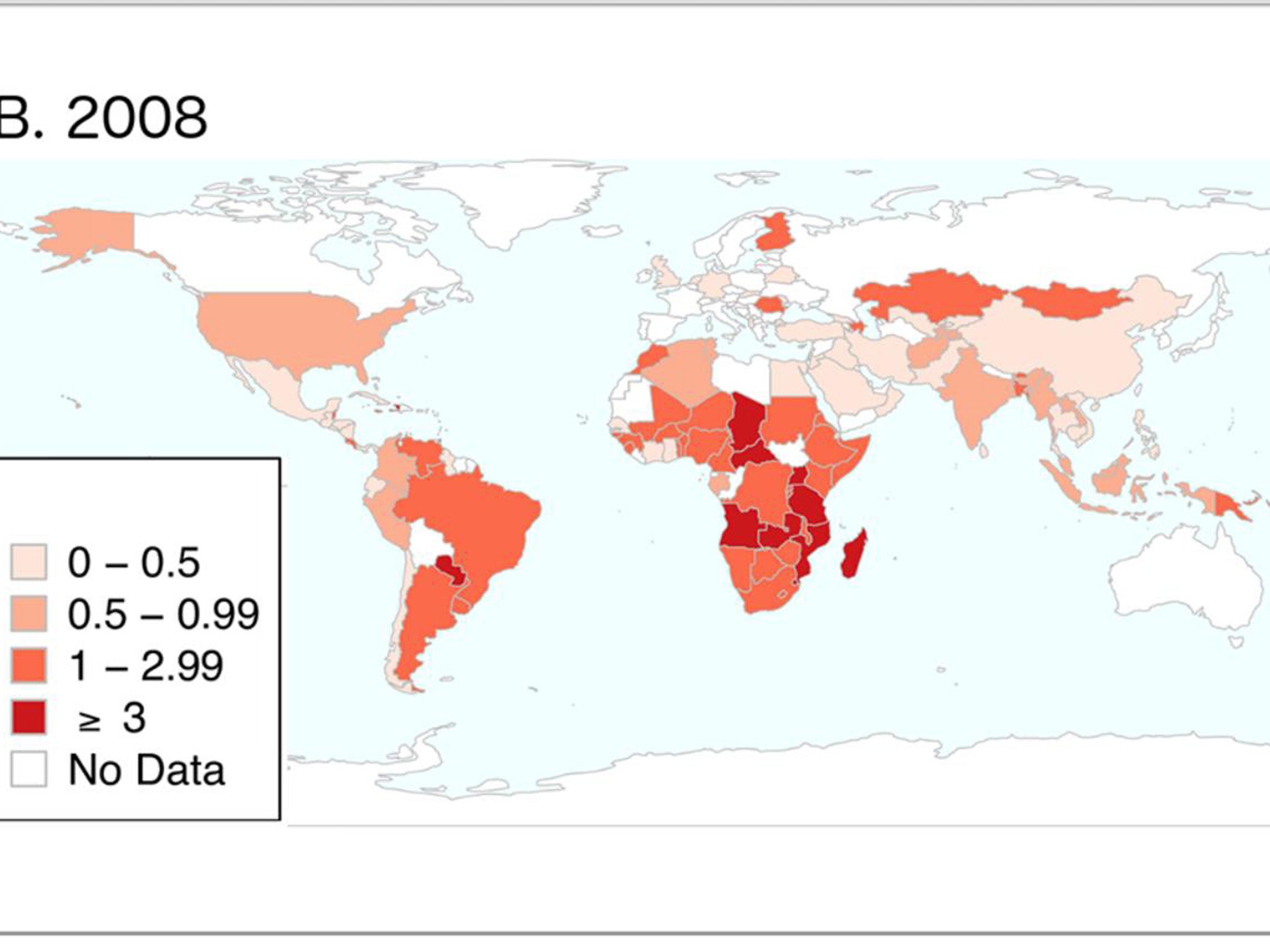

Scientists have drawn up maps showing the different rates of syphilis around the world.

The researchers, from the Institute of Tropical Medicine in Belgium, said it was clear that the development of penicillin had played an "important role" in the disease's decline after production of the antibiotic was stepped up in the years following the Second World War.

However, they said in some parts of the world, particularly sub-Saharan Africa, syphilis had demonstrated "more resilience".

They admitted their study had "numerous limitations," but said such work could lead to greater understanding of the disease.

The researchers used figures from the testing of pregnant women for sexually transmitted infections (STIs). They said these were thought to give a better idea of the prevalence of syphilis in the general public than data from STI screening, which can be biased towards high-risk populations.

By 1959, 600 tons of penicillin were being produced a year, providing the first effective treatment for a disease that had been a scourge of humanity for centuries. Sir Alexander Fleming, the Scottish scientist who accidentally discovered its antibiotic effect, was lauded around the world partly because of this.

And the researchers said there was "little doubt that its widespread use played an important role in the decline of syphilis rates".

In a paper published in the journal PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases, they wrote: "Our findings were that in most populations syphilis prevalence dropped to under one per cent before 1960."

The UK appears to have benefitted from Sir Alexander's discovery sooner than most. In 1947 in the UK, just 0.4 per cent of antenatal tests of pregnant women found evidence of syphilis.

The disease declined "more slowly" in India with a figure of 1.6 per cent in 1973, but then just 0.1 per cent in 1982. In Japan and Singapore the rate had fallen below two per cent by 1955.

In apartheid South Africa, the figures among the black population were "high in the pre-penicillin period", the researchers said.

They then "dropped in the post-penicillin period but then plateaued at around 6 per cent until the end of the 20th century when [the rates] dropped precipitously to just above 1 per cent".

The rate among white South Africans was under one per cent in 1991, when the first large-scale study was carried out.

The researchers found no evidence of an association between syphilis rates and GDP per capita, health expenditure, screening/treatment or circumcision prevalence.

"These findings, considered in conjunction with other types of evidence we review, such as the strong correlations at population level between syphilis prevalence and those of Herpes Simplex Virus-2 prevalence and HIV prevalence, suggest that common risk factors may underpin the spread of all three of these sexually transmitted diseases," they added.

"Establishing what these factors are is of great importance to improve the health of highly affected populations such as those in sub-Saharan Africa."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments