Astronomers discover supernova ‘twice as bright or energetic’ as any ever recorded

Death of massive star 4.6 billion light years away could aid search for universe’s oldest stars

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Astronomers believe they have discovered a supernova at least twice as bright and energetic as any previously recorded.

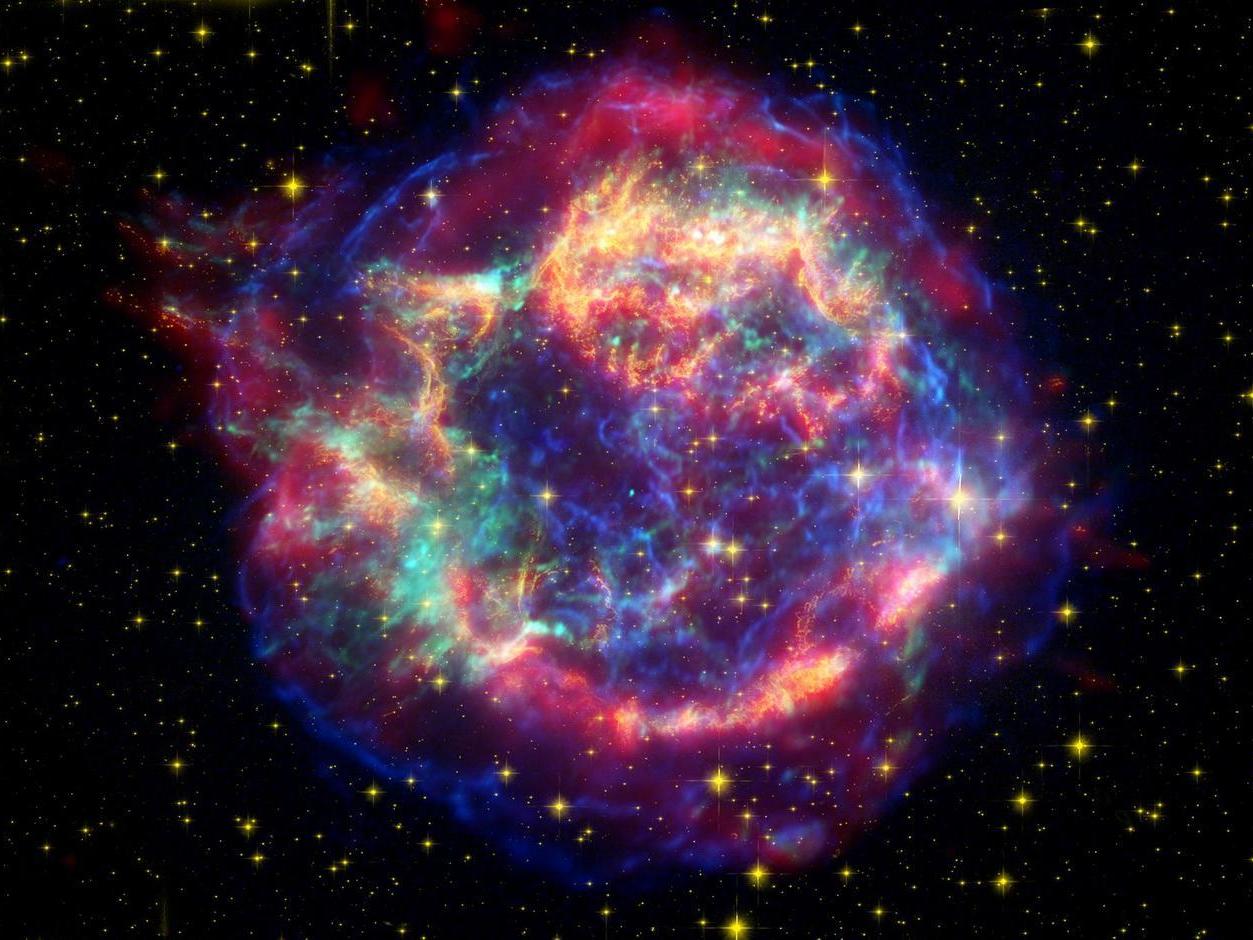

A supernova is the explosion that occurs in the final throes of a dying, powerful star – with some of the largest thought to cause black holes to form.

The scientists believe their discovery to be an extremely rare “pulsational pair-instability” supernova likely triggered by two huge stars, which merged before detonating in the biggest solar explosion ever witnessed.

Such an event so far only exists in theory and has never been confirmed through astronomical observations.

The explosion 4.6 billion light years away first piqued the scientists’ attention because it appeared to be alone in the cosmos. In reality, it was so bright it had hidden the surrounding galaxy.

“While many supernovae are discovered every night, most are in massive galaxies,” said Dr Peter Blanchard, from Northwestern University. “This one immediately stood out for further observations because it seemed to be in the middle of nowhere.

“We weren’t able to see the galaxy where this star was born until after the supernova light had faded.”

The team, which also includes experts from Harvard and Ohio University, continued to observe the explosion dubbed SN2016aps for two years, until it faded to 1 per cent of its peak brightness.

Using these measurements, they calculated the mass of the supernova was between 50 to 100 times greater than our sun. Typically, supernovae have masses of between eight and 15 solar masses.

Supernovae can be measured by the total energy of the explosion, and the amount of that energy that is emitted as observable light, or radiation, according to lead study author Dr Matt Nicholl, of the University of Birmingham.

“In a typical supernova, the radiation is less than 1 per cent of the total energy,” he said. “But in SN2016aps, we found the radiation was five times the explosion energy of a normal-sized supernova. This is the most light we have ever seen emitted by a supernova.”

The scientists, who examined the light spectrum, say the explosion was powered by a collision between the supernova and a massive shell of gas, shed by the star mere decades before it exploded.

“Stars with extremely large mass undergo violent pulsations before they die, shaking off a giant gas shell,” Dr Nicholl said.

“This can be powered by a process called the pair instability, which has been a topic of speculation for physicists for the last 50 years. If the supernova gets the timing right, it can catch up to this shell and release a huge amount of energy in the collision.

“We think this is one of the most compelling candidates for this process yet observed, and probably the most massive.”

The supernova “also contained another puzzle”, added Dr Nicholl. “The gas we detected was mostly hydrogen – but such a massive star would usually have lost all of its hydrogen via stellar winds long before it started pulsating.

“One explanation is that two slightly less massive stars of around say 60 solar masses had merged before the explosion. The lower-mass stars hold onto their hydrogen for longer, while their combined mass is high enough to trigger the pair instability.”

The team hopes their research – published on Monday in the journal Nature Astronomy – will help other astronomers in their bid to find the oldest stars in the universe once Nasa’s new space observatory is completed.

Scientists believe massive stars were more prevalent in the early universe, and it is hoped this discovery will shed more light on how to find them.

Professor Edo Berger, of Harvard University, said: “Now that we know such energetic explosions occur in nature, Nasa’s new James Webb Telescope will be able to see similar events so far away that we can look back in time to the deaths of the very first stars in the universe.”

Additional reporting by PA

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments