The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

‘Super Earth’ planet orbiting nearby star discovered by astronomers

Discovery marks end of long search for exoplanets around Barnard's star

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Six light years away, a “super-Earth” planet has been found orbiting beyond our solar system - a discovery astronomers hope will help them with their research on more distant parts of the universe.

Super-Earths are planets with masses larger than the Earth itself, although not as large as giant planets like Uranus, which is more than 14 times larger the our planet.

It was discovered orbiting Barnard's star, one of the nearest neighbouring stars to our own solar system.

Smaller and older than our sun, Barnard's star belongs to a category of relatively small celestial objects known as red dwarfs.

Astronomers have identified these as the best places to search for exoplanets, or planets outside our solar system.

"Barnard's star is an infamous object among astronomers and exoplanet scientists, as it was one of the first stars where planets were initially claimed but later proven to be incorrect,” said Dr Guillem Anglada Escude from Queen Mary University of London. “Hopefully we got it right this time."

Reporting their findings in the journal Nature, the scientists said that after careful analysis of nearly two decades’ worth of data they are 99 per cent confident the exoplanet they have identified is there.

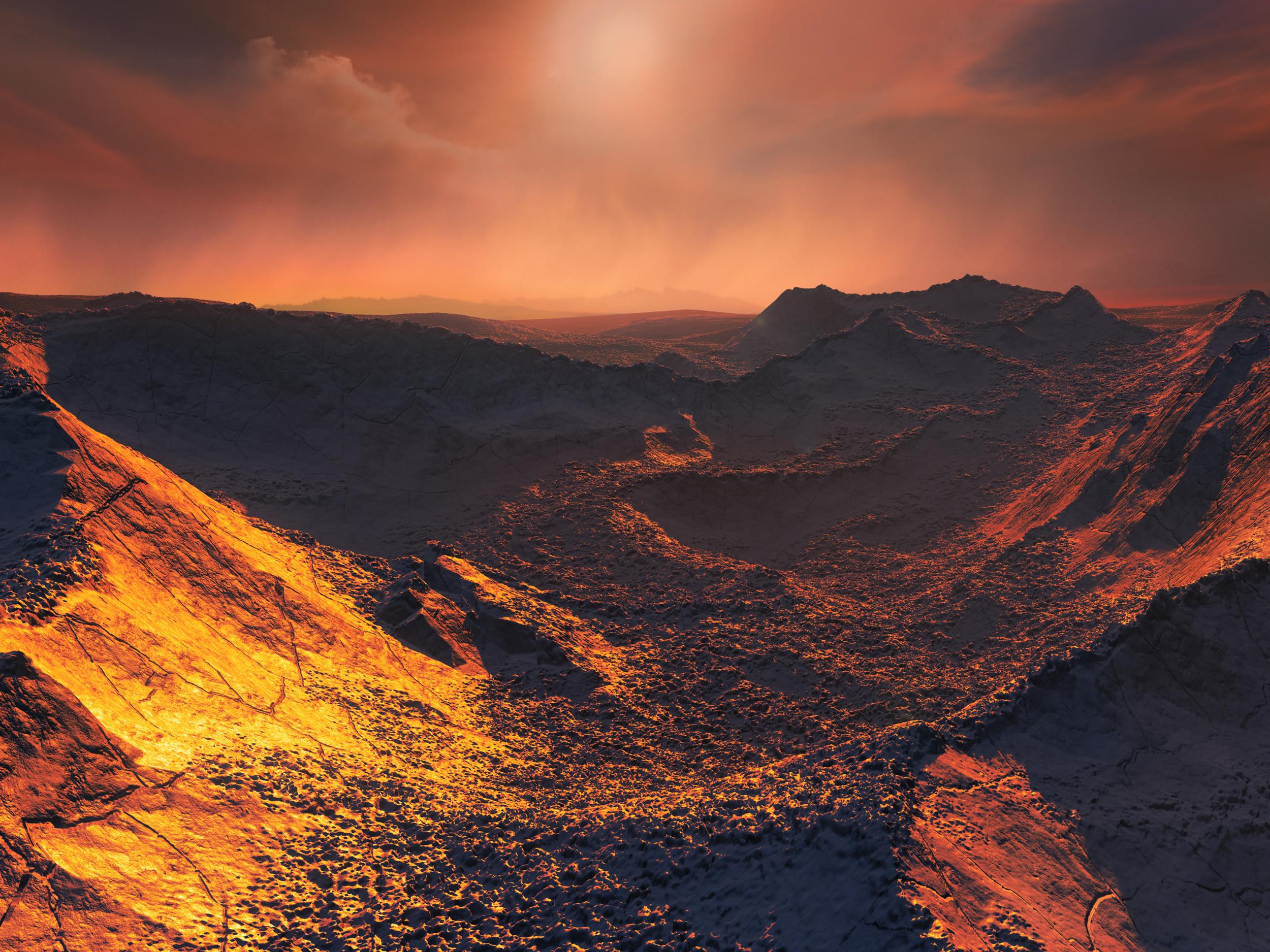

It is located beyond the habitable zone for its star, at a distance beyond the so-called “snow line” at which liquid water and any possible chance of life cannot exist.

Planets beyond our solar system are extremely faint compared to the stars they orbit, meaning they are difficult to identify even using the largest telescopes currently available.

As a result, most of what astronomers know about they mysterious worlds comes from indirect measurements of variations in light beamed down to Earth from the exoplanets’ host stars.

One technique that uses such measurements is known as radial velocity, which can be used to assess wobbles the planet’s gravity creates in the star’s orbit. These wobbles affect the light coming from the star, which can then be detected by astronomers.

"This technique has been used to find hundreds of planets," said Dr Paul Butler, a team member from the Carnegie Institution for Science who helped pioneer the method.

"We now have decades of archival data at our disposal. The precision of new measurements continues to improve, opening the doors to new parameters of space, such as super-Earth planets in cool orbits like Barnard's star b."

The scientists want to collect more data to confirm the planet’s presence, and say it could provide an excellent target to test using the latest in space observation technology such as Nasa’s planned Wide Field Infra Red Survey Telescope.

If using such technologies they can observe the planet directly, it will open up their understanding of the kinds of planets that are forming around other stars in distant space.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments