Study describes oldest known evidence of fossilised skin

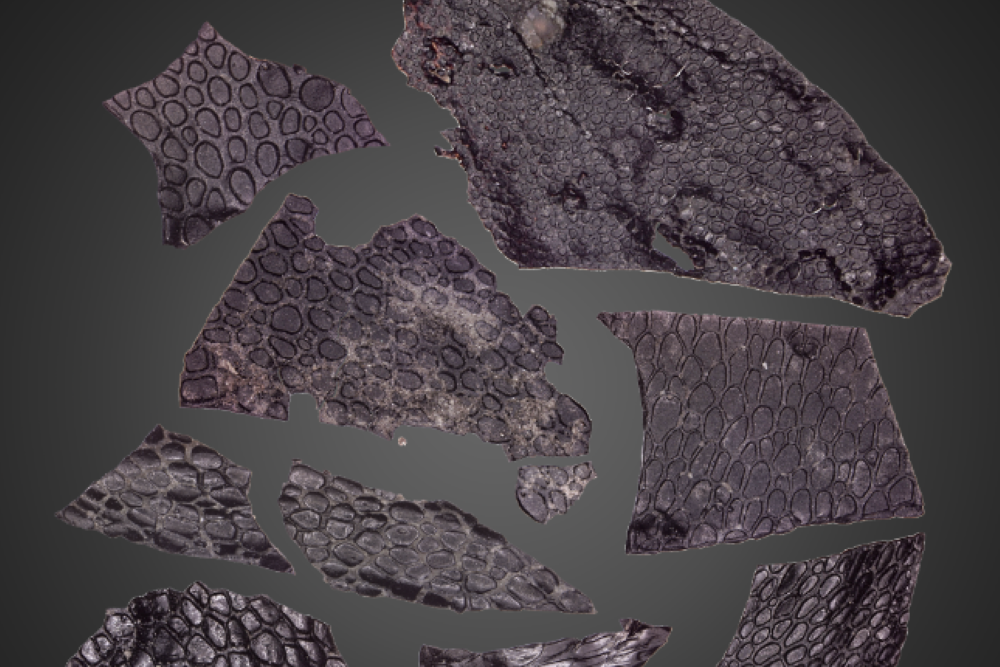

The skin, which has a pebbled surface and most closely resembles crocodile skin, belonged to an early species of Palaeozoic reptile.

A new study describes the oldest known evidence of fossilised skin.

The skin, which has a pebbled surface and most closely resembles crocodile skin, belonged to an early species of Palaeozoic reptile, 541-252 million years ago.

Researchers said it is the oldest example of preserved epidermis, the outermost layer of skin in terrestrial reptiles, birds, and mammals, which was an important evolutionary adaptation in the transition to life on land.

First author Ethan Mooney, who worked on the project as an undergraduate with palaeontologist Robert Reisz at the University of Toronto, said: “Every now and then we get an exceptional opportunity to glimpse back into deep time.

“These types of discoveries can really enrich our understanding and perception of these pioneering animals.”

It is rare for skin and other soft tissues to be fossilised, but the researchers think that skin preservation was possible in this case because of the unique features of the Richards Spur limestone cave system in Oklahoma, USA.

The features include fine clay sediments that slowed decomposition, oil seepage, and a cave environment that was likely to have been an oxygen-less environment.

Finding such an old skin fossil is an exceptional opportunity to peer into the past and see what the skin of some of these earliest animals may have looked like

The 3D fragment of fossilised skin is very small – smaller than a fingernail – and microscopic examination revealed epidermal tissues.

Mr Mooney said: “We were totally shocked by what we saw because it’s completely unlike anything we would have expected.

“Finding such an old skin fossil is an exceptional opportunity to peer into the past and see what the skin of some of these earliest animals may have looked like.”

The skin shares features with ancient and current reptiles, including a pebbled surface similar to crocodile skin, and some skin structures that resemble those in snakes and worm lizards.

However, because the skin fossil is not associated with a skeleton or any other remains, it is not possible to identify what species of animal or body region the skin belonged to.

Researchers suggest that the fact that this ancient skin resembles the skin of reptiles alive today shows how important these structures are for survival.

Mr Mooney said: “The epidermis was a critical feature for vertebrate survival on land.

“It’s a crucial barrier between the internal body processes and the harsh outer environment.”

The researchers said this skin may represent the ancestral skin structure that allowed for the eventual evolution of bird feathers and mammalian hair follicles.

– The research is published in the journal Current Biology.

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks