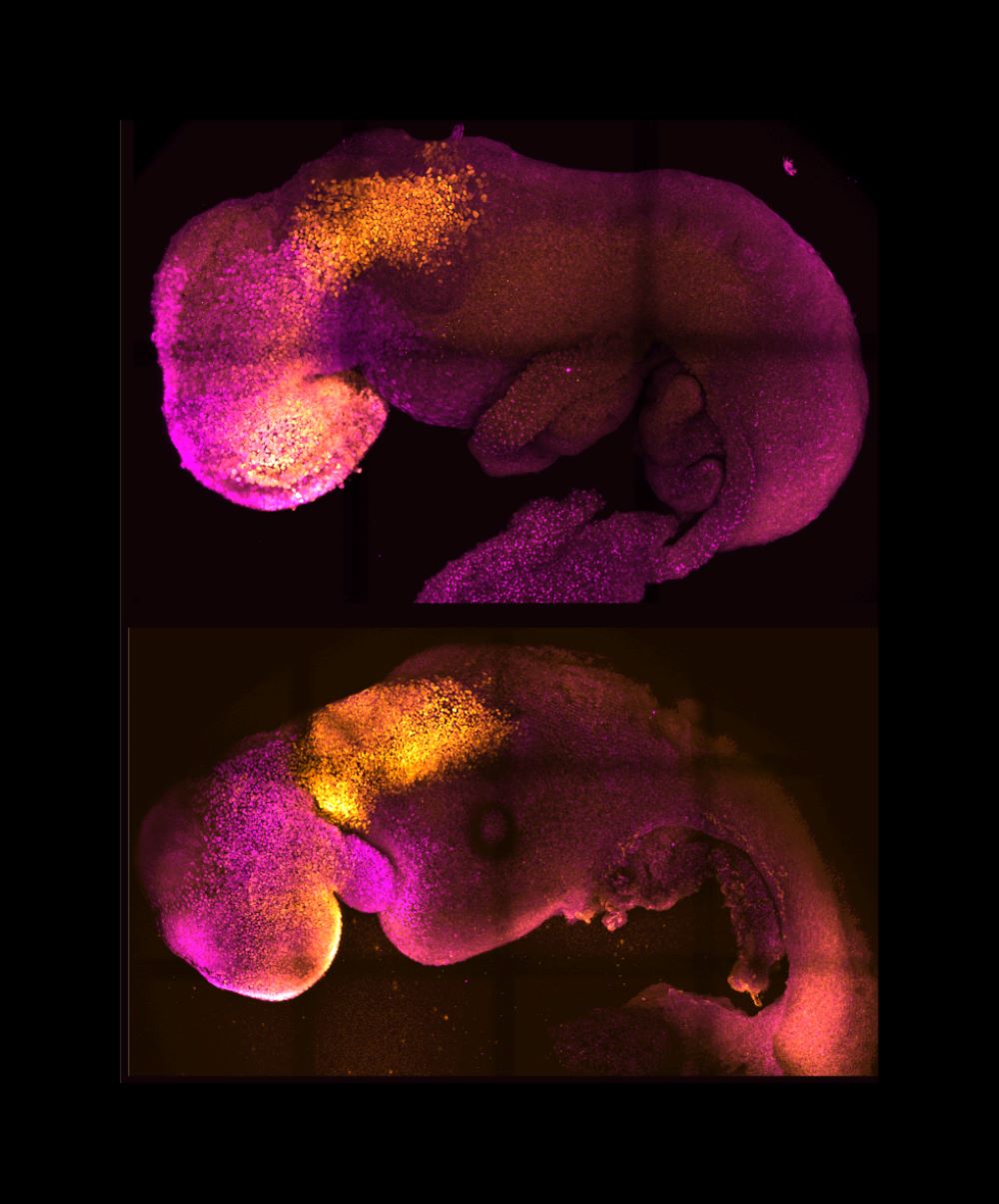

Synthetic embryo with brain and beating heart grown from mouse cells for first time ever

The results could be used to guide repair and development of synthetic, or artificial, human organs for transplantation, experts suggest.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Researchers have created model embryos from mouse stem cells that form a brain, a beating heart and the foundations of all the other organs of the body.

The development could help researchers understand why some embryos fail while others go on to develop into a healthy pregnancy.

Additionally, the results could be used to guide repair and development of synthetic, or artificial, human organs for transplantation, experts suggest.

Magdalena Zernicka-Goetz, professor in mammalian development and stem cell biology at the University of Cambridge’s Department of Physiology, Development and Neuroscience, said: “Our mouse embryo model not only develops a brain, but also a beating heart, all the components that go on to make up the body.

“It’s just unbelievable that we’ve got this far.

“This has been the dream of our community for years, and a major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it.”

Although the current research was carried out in mouse models, the researchers are developing similar human models which could help understand mechanisms behind crucial processes that would be otherwise impossible to study in real embryos.

UK law currently permits human embryos to be studied in the laboratory only up to the 14th day of development.

This has been the dream of our community for years, and a major focus of our work for a decade and finally we’ve done it

If the methods developed are shown to be successful with human stem cells in future, they could also be used to guide development of synthetic organs for patients awaiting transplants.

Prof Zernicka-Goetz said: “What makes our work so exciting is that the knowledge coming out of it could be used to grow correct synthetic human organs to save lives that are currently lost.

“It should also be possible to affect and heal adult organs by using the knowledge we have on how they are made.

“This is an incredible step forward and took 10 years of hard work of many of my team members – I never thought we’d get to this place.

“You never think your dreams will come true, but they have.”

The University of Cambridge scientists, led by Prof Zernicka-Goetz, developed the embryo model without eggs or sperm.

Instead they used stem cells – the body’s master cells that can become almost any type of cell in the body.

In order for a human embryo to successfully develop, there needs to be a dialogue between the tissues that will become the embryo, and the tissues that will connect the embryo to the mother.

In the first week after fertilisation, three types of stem cells develop.

One of these will eventually become the tissues of the body, one will become the placenta, and the other is the yolk sac, where the embryo grows and where it gets its nutrients from in early development.

Many pregnancies fail at the point when the three types of stem cells begin to send mechanical and chemical signals to each other, which tell the embryo how to develop properly.

This accessibility allows us to manipulate genes to understand their developmental roles in a model experimental system

Prof Zernicka-Goetz explained: “So many pregnancies fail around this time, before most women realise they are pregnant.

“This period is the foundation for everything else that follows in pregnancy. If it goes wrong, the pregnancy will fail.”

Over the past decade Prof Zernicka-Goetz’s group in Cambridge has been studying these earliest stages of pregnancy, in order to understand why some pregnancies fail and some succeed.

She said: “The stem cell embryo model is important because it gives us accessibility to the developing structure at a stage that is normally hidden from us due to the implantation of the tiny embryo into the mother’s womb.

“This accessibility allows us to manipulate genes to understand their developmental roles in a model experimental system.”

To guide the development of their synthetic embryo, the researchers put together cultured stem cells representing each of the three types of tissue in the right proportions and environment to promote their growth and communication with each other, eventually self-assembling into an embryo.

“This period of human life is so mysterious, so to be able to see how it happens in a dish – to have access to these individual stem cells, to understand why so many pregnancies fail and how we might be able to prevent that from happening – is quite special,” said Prof Zernicka-Goetz.

Researchers say a big advance in the study is the ability to generate the entire brain which has been a major goal in the development of synthetic embryos.

The findings are published in the Nature journal.