Stem cell breakthrough: Japanese scientists discover way to create 'embryonic-like' cells without the ethical dilemma

Experts say the ground-breaking discovery could pave way for routine use of stem cells in medicine

A new way of creating stem cells that is cheaper, faster and more efficient than before could transform the ability of scientists to develop "personalised medicine" where a patient’s own healthy skin or blood cells can be used to repair damaged tissues, such as heart disease or brain injury.

Japanese scientists announced today that they had created stem cells – which are essential for bodily repair – by simply bathing blood cells in a weakly acidic solution for half an hour, triggering a remarkable reversion to the cells’ original embryonic state.

Researchers in Britain said they were astonished by the ease with which their colleagues in Japan had created embryonic-like stem cells with the ability to develop into any of the dozens of highly specialised cells of the body, ranging from cardiac-muscle cells to the nerve cells of the brain and spinal cord.

It opens up the prospect of doctors taking small samples of skin or blood from a patient and using the tissue to create stem cells that could be injected back into the same patient as part of a "self-repair" kit to mend damaged organs without the risk of tissue rejection.

The stunning breakthrough was even more striking in that it was made by a young Japanese researcher called Haruko Obokata of the Riken Centre for Developmental Biology in Kobe who could not at first believe her own results – and when she did finally believe them she found it just as difficult to persuade her colleagues that they were not a mistake

"I was really surprised the first time I saw [the stem cells]… Everyone said it was an artifact – there were some really hard days," Dr Obokata said. Although the research was carried out on mouse cells, it should also work with human cells, she said.

"It’s exciting to think of the new possibilities this finding provides us not only in areas like regenerative medicine but perhaps in the study of cell senescence [ageing] and cancer as well. As regards human cells, that project is underway," she added.

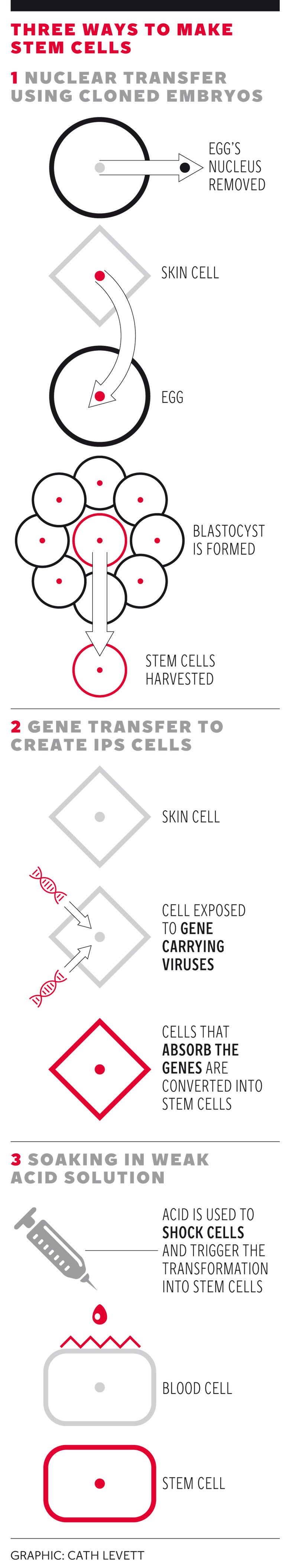

Previously, stem cells with the ability to develop into any specialised tissue – a phenomenon called pluripotency – could only be created either by extracting them from early embryos or by genetically manipulating adult cells to create so-called induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells.

However, creating and destroying human embryos raises ethical questions for many people and is fraught with practical difficulties, while using iPS cells in human medicine is raises safety concerns about using genetically modified cells. Both techniques are also costly, inefficient and time-consuming.

The new approach, based simply on bathing blood or skin cells in a weak solution of citric acid for 30 minutes, is not only much quicker and cheaper than the previous two techniques, it is also so simple that it could be carried out in labs without any particularly specialised knowledge or equipment.

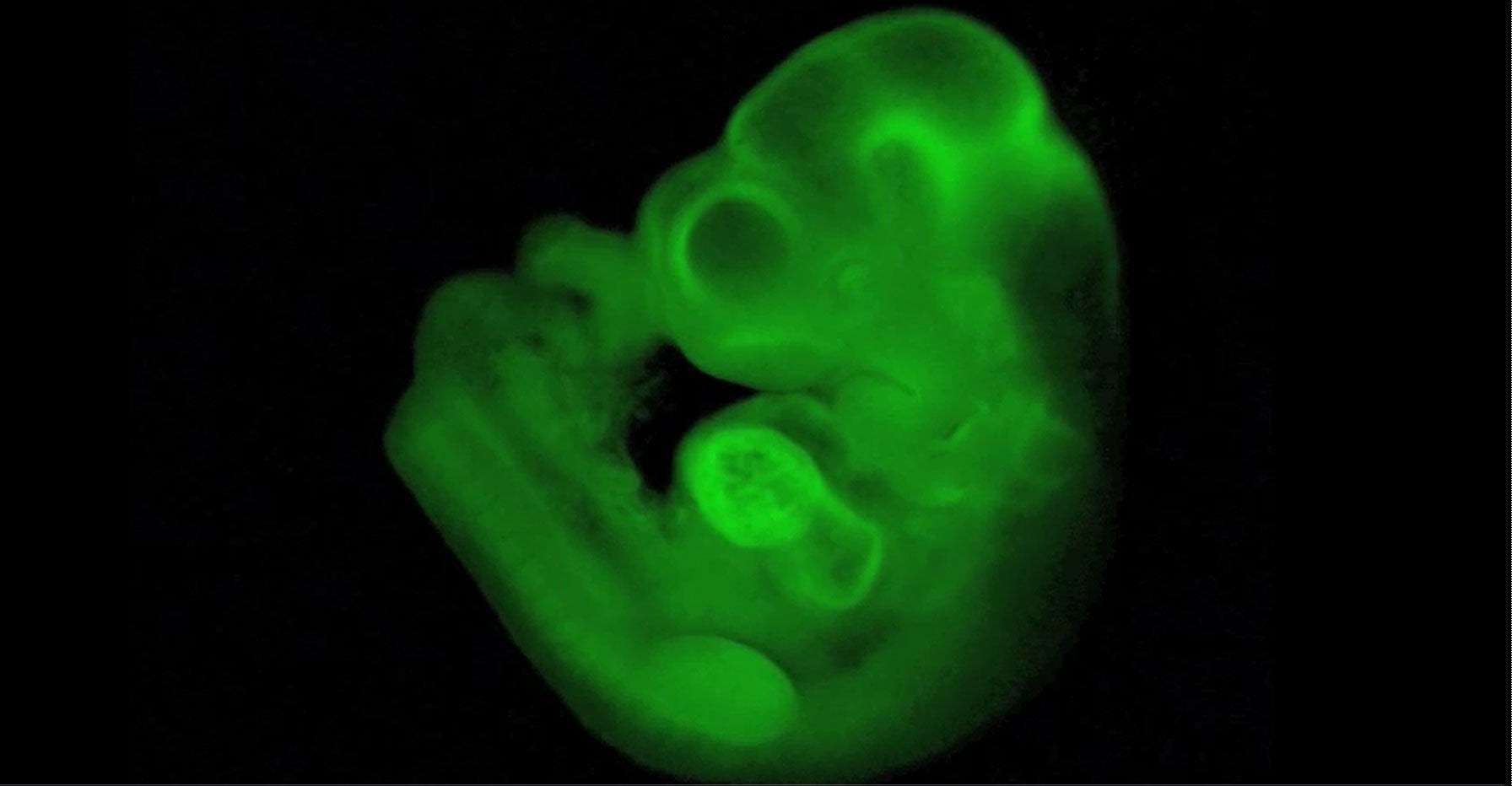

To test that the cells were truly pluripotent, Dr Obokata and her colleagues labelled them with a green fluorescent gene, injected them into early mouse embryos and found that they colonised every tissue of the developing foetus, even its umbilical cord – which does not happen with classical embryonic stem cells and iPS cells.

The Japanese scientists, who collaborated with Charles Vacanti of Harvard Medical School in Boston, said that in addition to blood cells, they have also created stem cells from the brain, skin, muscle, fat, bone-marrow, lung and liver tissues of newborn mice. They have called the technique stimulus-triggered acquisition of pluripotency (STAP) and believe there may be other ways of “ shocking” adult cells to revert to their embryonic condition other than bathing them in a weak acid solution.

Professor Vacanti said: "It may not be necessary to create an embryo to acquire embryonic stem cells. Our research findings demonstrate that creation of an autologous pluripotent stem cell – a stem cell from an individual that has the potential to be used for therapeutic purpose – without an embryo, is possible."

Scientists in Britain said the findings were extraordinary and unexpected. The results rewrite the rulebook on how the specialised cells of the mammalian body are meant to behave once they have travelled down what was thought to be the one-way street of cell differentiation, they said.

"Obakata’s approach in the mouse is the most simple, lowest cost and quickest method to generate pluripotent cells from mature cells," said Professor Chris Mason, an expert in regenerative medicine at University College London.

"If it works in man, this could be the game changer that ultimately makes a wide range of cell therapies available using the patient’s own cells as starting material – the age of personalised medicine would have finally arrived," Professor Mason said.

"Who would have thought that to reprogram adult cells to an embryonic stem cell-like (pluripotent) state just required a small amount of acid for less than half an hour? An incredible discovery," he added.

Professor Robin Lovell-Badge, head of stem cell biology at the MRC’s National Institute for Medical Research in north London, said: "It is going to be a while before the nature of these cells are understood, and whether they might prove to be useful for developing therapies, but the really intriguing thing to discover will be the mechanism underlying how a low pH [acidic] shock triggers reprogramming. And why it does not happen when we eat lemon or vinegar or drink cola?"

Watch professor Chris Mason from UCL discuss the revolutionary new approach

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments