Stargazing in July: The name of the moon

Towards the end of July we’ll be treated to an orange-red moon. That’s not an official name, but it’s how the full moon of 24 July will appear in colour, writes Nigel Henbest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The moon has many names. I don’t just mean that it’s called la lune in French, der mond in German or mwezi in Swahili. You’ll hear astronomers talking about the blood moon, a blue moon, the worm moon and even a black moon. They all describe different aspects of the full moon, when our companion world is fully illuminated by sunlight and appears at its biggest and brightest each month.

Towards the end of July we’ll be treated to an orange-red moon. That’s not an official name, but it’s how the full moon of 24 July will appear in colour. Around midsummer, the full moon never rises far above the southern horizon (just as the sun lies low in the south in winter). As a result, its light has to travel a long way through the Earth’s atmosphere to reach us. Though moonlight is white, particles in the air scatter away much of its blue light, leaving mostly red wavelengths to reach our eyes.

A blood moon also describes the moon’s colour, but this time a much deeper coppery hue as the moon enters the Earth’s shadow in a total lunar eclipse. With the Earth cutting off the sun’s light, the moon should disappear from sight; but our planet’s atmosphere bends some of the sunlight round to shine on the moon’s obscured face. Traversing so much of the Earth’s air, this illumination of the lunar surface is a deep bloody red.

A blue moon is a different kind of beast. Very occasionally, a forest fire or volcanic eruption can fill the upper atmosphere with sooty specks that are just the right size to filter out red light, so the full moon appears distinctly azure. That happens only once every few decades, most noticeably back in 1950 after a huge fire in the Canadian forests.

But you’ll hear the media report a blue moon maybe every couple of years. In this case, don’t expect to see the moon actually change colour. This kind of blue moon was first named by a 19th-century American farming almanac, for seasons which hosted not just three full moons but four. The Maine Farmer’s Almanac called the extra full moon a “blue” moon, and the next seasonal blue moon will rise on 22 August. Over time, the usage changed from a season with an extra full moon to a month that has two full moons. The most recent blue moon of this kind was on 31 October 2020, and the next falls on 30 August 2023; they occur on average once every two to three years.

We can see two full moons in the same month because the period between full moons is 29.53 days, slightly less than the length of most months. But February, of course, has only 28 or 29 days, and that means there can be years when there’s no full moon at all in February. The last time this happened was in 2018, and the “missing” full moon was called a black moon.

Leaving aside such exotica, people around the world have given names to the 12 full moons which occur regularly, each calendar month of the year. In Britain and Europe, where farmers are so dependent on grain crops, the most important rose in September, aiding farmers out in the field, and they named it the harvest moon. The following month, when the arable crops had been gathered, people out pursuing more mobile food relied on the illumination of the hunter’s moon.

The names you’ll hear for the other full moons of the year largely come from the indigenous people living in the eastern regions of North America. So the year starts with the wolf moon and the snow moon. March sees the worm moon, named either for the first emergence of earthworms or for beetle larvae which start hatching in tree bark. And April is the month of the pink moon – nothing to do with its colour, but it’s the season when the pink blossoms of the moss phlox appear. Then we have the flower moon and the strawberry moon, bringing us to this month’s incarnation, the buck moon, when the native deer have the most splendid display of antlers.

August has the sturgeon moon. Then, after the harvest and hunter’s moons, we have the beaver moon in November, and the aptly named cold moon rounding off the year in December.

What’s up

As the light fades from the sky on these summer evenings, look low on the north-western horizon to spot a brilliant light in the sky that appears before any of the others. The glorious evening star is in fact our neighbour planet Venus, shining brilliantly as the sun illuminates its all-enveloping clouds.

In mythology, Venus was the goddess of love; and this month she has a tryst with Mars, the fiery planet of war. At the start of July, Mars lies to the upper left of Venus; but the evening star moves rapidly in that direction, and you’ll see the two planets up close and personal on 12 and 13 July. The only disappointment is that Mars currently lies far from the Earth and so appears faint – 200 times dimmer than Venus, and you’ll probably need binoculars to view this conjunction clearly.

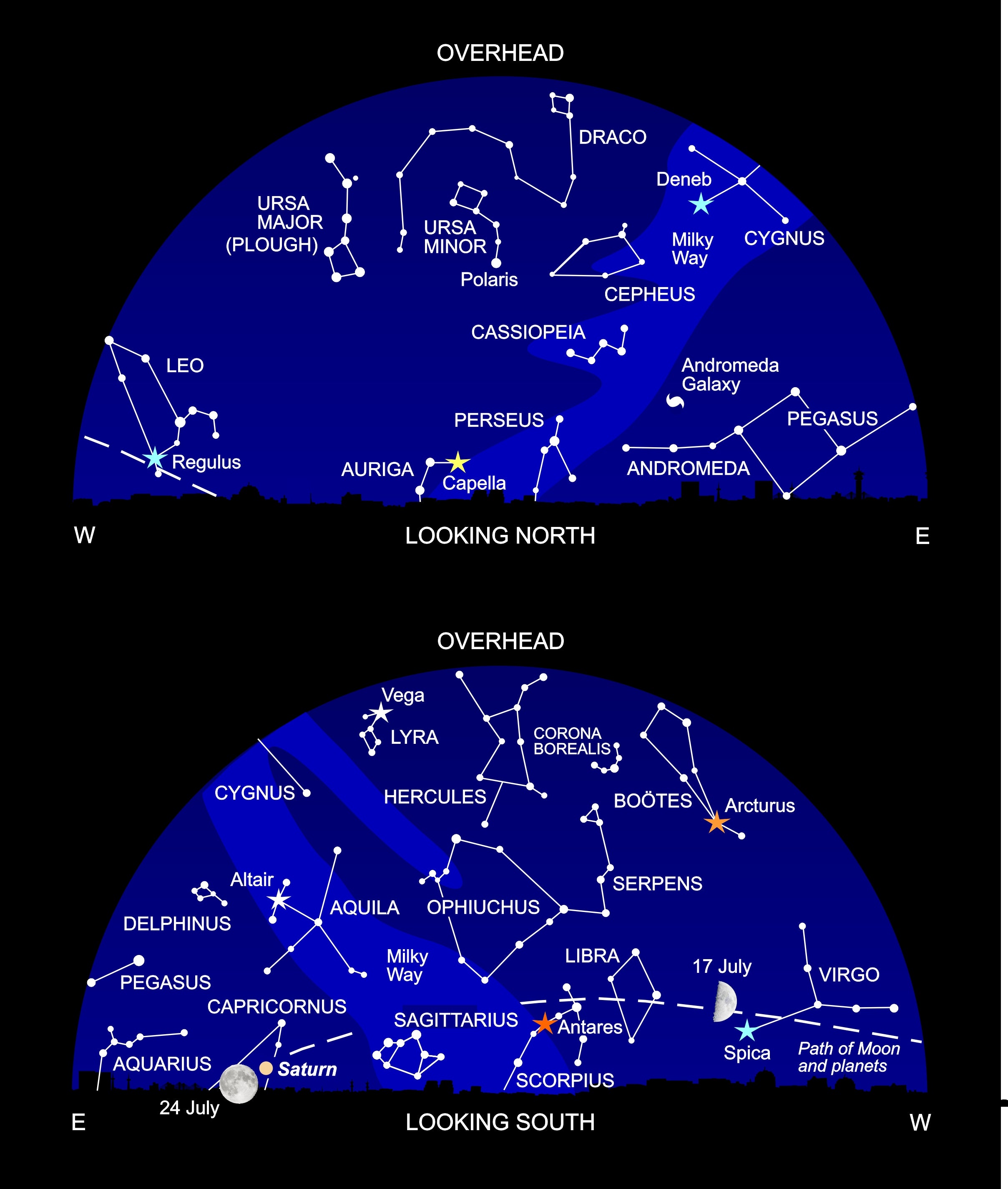

The bright red star low in the south is Antares, marking the heart of the celestial scorpion, Scorpius. It’s one of the few constellations that resembles its namesake, with the stars to the upper right forming its head and Libra originally depicting its ferocious claws. To the lower left of Antares, a curved line of stars outlines the scorpion’s tail and sting, though you need to travel to southern climes to view the beast’s lower portions in all their glory.

Above Antares lie two huge but dim constellations: Ophiuchus (the Serpent Bearer) and the great hero Hercules. They’re framed by the bright stars Arcturus to the right, Altair on the left and Vega almost overhead.

Around 11 pm, Saturn is rising in the south-east: it’s close to the full moon on 24 July. A little later, even showier Jupiter ascends above the horizon to the left of Saturn, the two giant worlds dominating the southern skies for the rest of the night.

Diary

1 July, 10:10pm: Last quarter moon

4 July: Mercury at greatest elongation west

5 July: Earth at aphelion (furthest from the sun)

10 July, 2:16am: New moon

11 July: Crescent moon near Venus and Mars

12 July: Venus near Mars, with the crescent moon to upper left

13 July: Venus near Mars

16 July: Moon near Spica

17 July, 11:10am: First quarter moon near Spica

20 July: Moon near Antares

21 July: Venus near Regulus

24 July, 3:37am: Full moon near Saturn

25 July: Moon near Jupiter

29 July: Mars near Regulus

31 July, 2:16pm: First quarter moon

Philip’s 2021 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments