Stargazing in March: A jewel box above our heads

While the gemstones at a jewellery shop owe their kaleidoscopic colours to the variety of elements they contain, a star’s colour depends on only one factor, its temperature, writes Nigel Henbest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

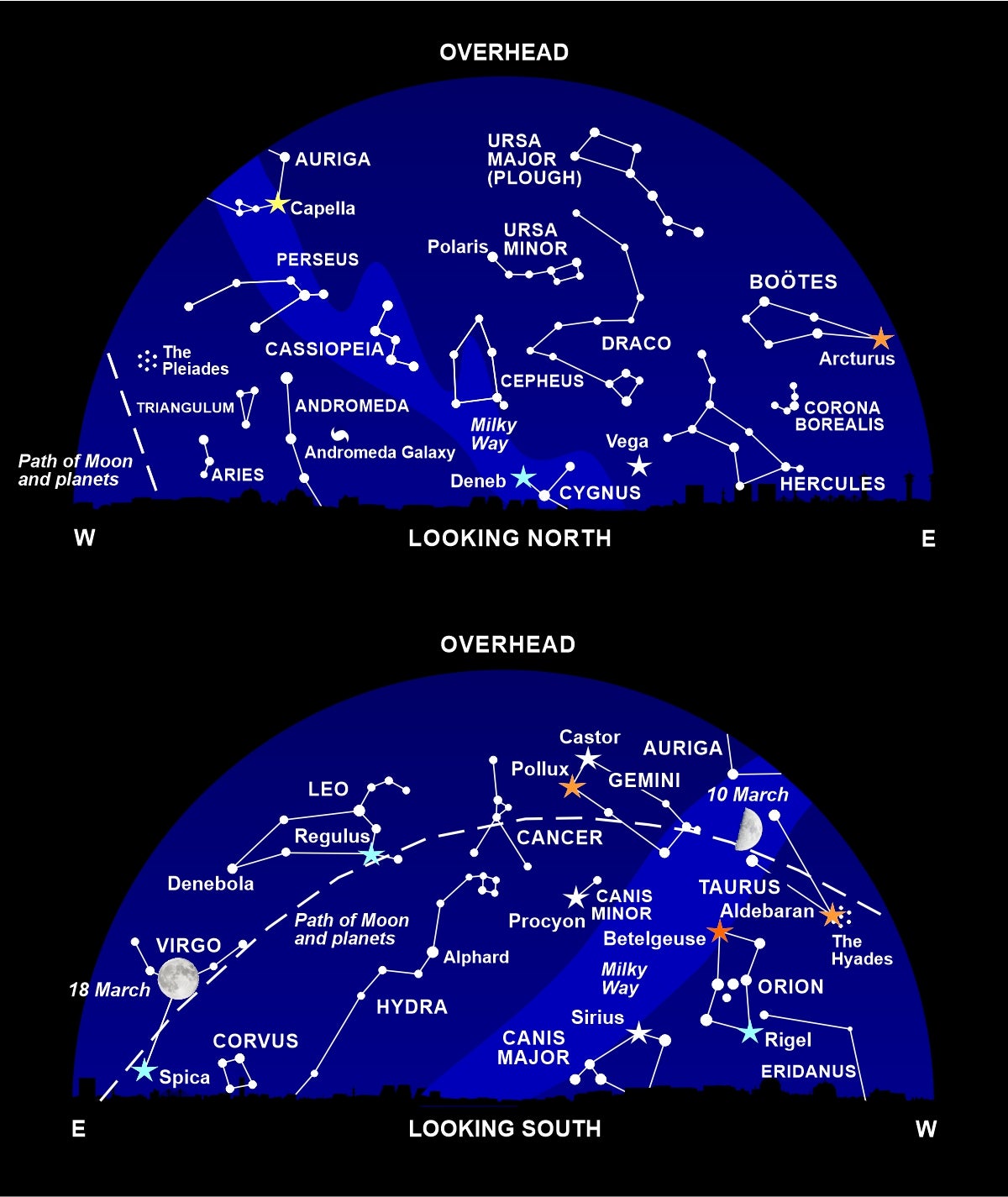

Your support makes all the difference.A celestial jewel box lies open above our heads this month, each star a subtly tinted gem. To the west, Betelgeuse is Orion is a ruby. Regulus and spica to the south and east are pale sapphires. Arcturus and Aldebaran are topaz, along with Pollux – its hue contrasting with its neighbour, Castor, which along with brilliant Sirius is a pure diamond. Finally, seek out Citrine Capella, a colour-match to the sun.

To the unaided eyes, these shades are understated. But you’ll see the tints in their full glory through binoculars. And a telescope reveals that fainter, apparently white, stars are also rich in colour.

While the gemstones at a jewellery shop owe their kaleidoscopic colours to the variety of elements they contain, a star’s colour depends on only one factor, its temperature – just as a poker stuck into an open fire will glow red, orange, yellow and white as it heats up.

Our sun is a typical star: a giant ball of incandescent gas, powered by nuclear reactions at its core. If you could lower a thermometer into the sun’s surface gases, you’d record a temperature of 5,500C. That’s hot enough to boil or vapuorise any substance known. NASA’s Parker Solar Probe, currently flying close to our local star, has a sunshield made of the most heat resistant substances we know, carbon-carbon composite coated with alumina, but even that would be destroyed at 1,400C.

The sun’s temperature means that its surface shines with a yellow glow. Capella is about the same temperature, and so it looks the same colour even though it is a much larger and more massive star.

A star that’s cooler than the sun appears in shades of orange or red; a hotter star is white or bluish-white. That’s where astrophysicists and plumbers differ: you expect the red tap in your bathroom to deliver hot water, while the blue one is the cold tap!

Orange stars have temperatures around 4,000C, while the reddest bright star on view tonight, betelgeuse, glowers at a mere 3,300C. Above the surface, it’s cool enough that gaseous carbon atoms can condense into clouds of soot, which periodically dim the star’s light – as happened two years ago, when Betelgeuse seemed to drop to half its normal brightness.

Some 800 times wider than the sun, Betelgeuse is appropriately called a red giant. Many other cool stars are smaller than the sun, but they are among the dimmest stars known and none of them is visible to the naked eye. These red dwarfs include the sun’s nearest neighbour, Proxima Centauri, one-sixth the size of the sun and 500 times fainter.

Moving up the cosmic temperature scale, a pure-white star like Sirius or Castor shines hotter than the sun, at 10,000C. The heat rises more when we come to regulus and spica, the latter at 25,000C and showing a distinct blue tone. Spica’s temperature is awesome, but even this furnace is mild compared to the distant star WR 102 in Sagittarius. Blazing almost ten times hotter than spica, at 210,000C, WR 102 is the hottest star yet discovered.

The temperature of a star is one of its most basic properties, along with its mass and its size. And it still impresses me that you can learn something so fundamental about a star, without a huge telescope or computer power, but just with your own eyes.

What’s up

Spring is here, and summer is coming! This month sees the spring equinox, when the sun climbs northwards over the equator, and days become longer than nights. And near the end of March we jump into British summer time (BST), with longer and lighter evenings.

There’s a change in the night sky, too, with the winter constellations Orion, Taurus (the bull) and Canis Major (the great dog) sinking down into the western twilight. In their place, we’re treated to the larger fainter constellations of spring.

Chief amongst them is Leo, the majestic celestial lion. It’s one of the few constellations that resembles its namesake, an elegant crouching feline. Its heart is marked by the bright blue-white star regulus, while a curve of stars above delineates its neck and head. Denebola, the star at the far left, has a name that appropriately means “the tail”.

To the lower left, you’ll find spica – a star that’s a near-twin to regulus. Meaning “ear of corn”, Spica is the leading light of the constellation Virgo (the virgin). The rest of the constellation resembles a large letter Y, representing the virtuous lady’s back and shoulders.

Though it has few bright stars, Virgo is the second largest constellation. And below you’ll find the biggest constellation of all, Hydra (the water snake). Its sinuous coils stretch more than a quarter of the way around the sky.

Planet aficionados will have to wait until 4.30 am, when brilliant Venus rises in the southeast, far outshining all the stars. To its right you’ll find Mars, currently far from the Earth and only one-hundredth as bright as the morning star. Similar in brightness is the distant giant Saturn, lying below Venus this month.

Diary

8 March: moon between Aldebaran and the Pleiades

10 March, 10.45 am: first quarter moon

12 March: moon near Castor and Pollux

13 March: moon near Castor and Pollux

15 March: moon near Regulus

18 March, 7.17 am: full moon

19 March: moon near Spica

20 March, 3.33 pm: spring equinox; Venus at greatest elongation west

25 March, 5.37 am: last quarter moon

27 March, 1.00 am: British summer time (BST) begins

Philip’s 2022 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments