Stargazing in February: Is Betelgeuse about to blow?

Find out whether one of the brightest objects in the sky is about to go supernova and look out for a rare Mercury sighting

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Look up at the familiar figure of Orion, and you’ll notice something isn’t quite right. Poor Betelgeuse – the reddish star at the top left of the celestial hunter’s outline – is definitely ailing.

Betelgeuse is usually the 10th brightest star in the sky. Around 129 BC, the Greek astronomy Hipparchus devised a six-level division for the brightness of stars. Betelgeuse was “first magnitude”, smack in the middle of the 21 Premier League stars.

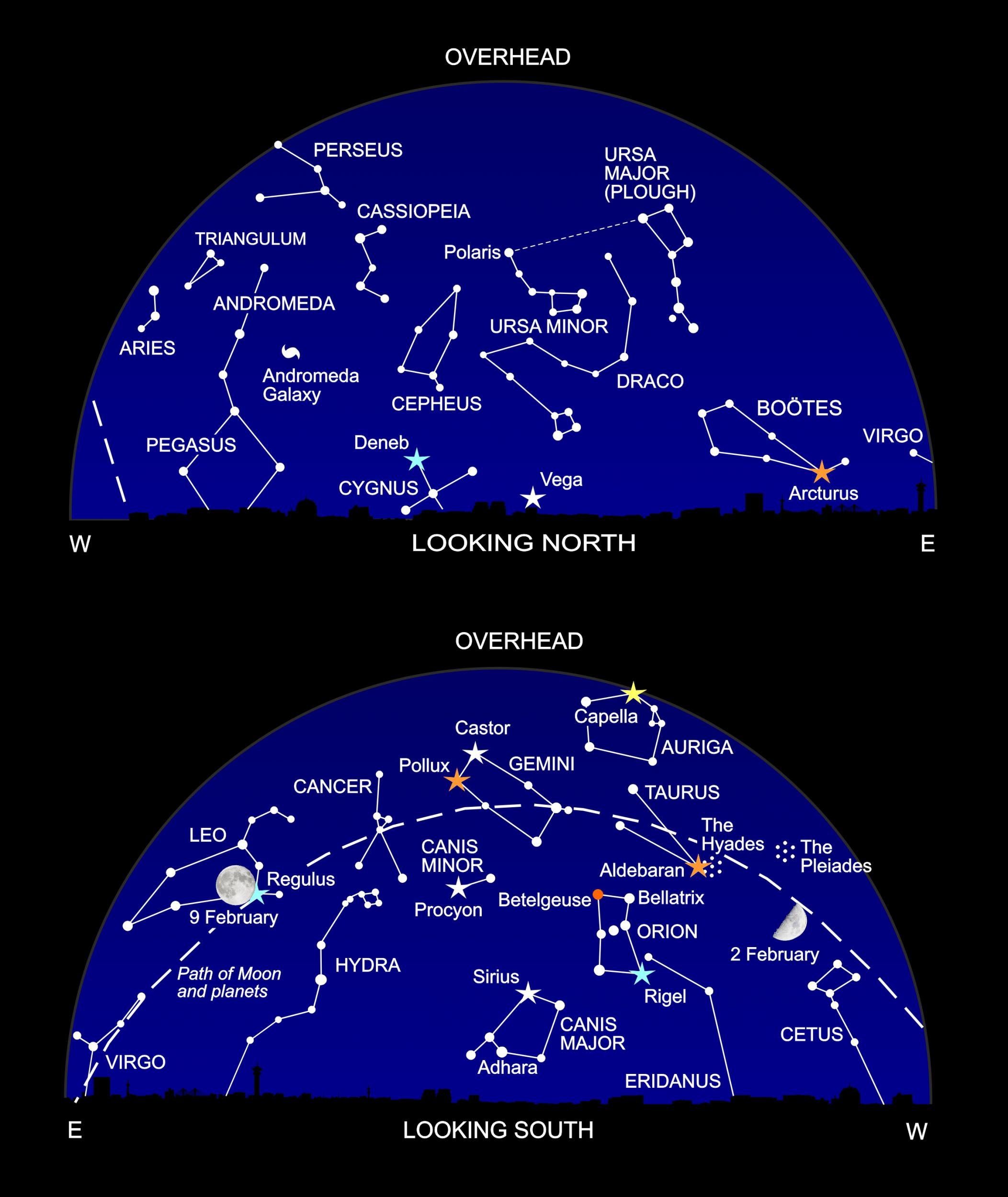

But since October, Betelgeuse has lost its shine. As you can see for yourself, it’s almost as faint as Orion’s other shoulder star, Bellatrix, and actually dimmer than the star lying below Sirius, Adhara. Betelgeuse is now only 23rd on the list, and officially second magnitude. We distinguish the first magnitude stars on our charts with a star-shaped symbol; this month, we’ve had to knock its points off.

What does this mean? Over the past few weeks, there have been a lot of reports in the media that Betelgeuse might be about to explode.

The reason is that Betelgeuse is a star approaching the end of its life. It was born about 10 billion years ago, as a heavyweight in the stellar maternity ward – weighing in almost 20 times heavier than our Sun.

Like our local star, it began to shine when its core heated up so much that hydrogen began to turn to helium, in the same nuclear reaction that makes a hydrogen bomb explode. While the Sun has carried on like this for billions of years, massive Betelgeuse ripped through its hydrogen fuel in just a few million years.

Now it was time for a major internal reshuffle. The central core shrank, and around it a witch’s brew of other nuclear reactions started up: helium burnt to carbon, which in turn produced neon and then silicon.

One day, these reactions will burn all the way through to iron. And that’s a problem. Iron is most stable of all the elements, and won’t undertake any more nuclear reactions. So the central nuclear reactor will switch off. The core will collapse, sending shock waves through the star that will make it explode as a brilliant supernova.

Let’s keep that thought in mind, and come back to the present. The outer layers of Betelgeuse have experienced an immense middle-age spread. The bloated star has grown so huge that – if you placed it at the centre of the Solar System – the star would engulf the orbit of the Earth, and extend out beyond the asteroid belt, almost all the way out to Jupiter.

The star is so large and diffuse that it wobbles like a jelly, pulsing in and out over the months and years. At the same time, huge bubbles of bright hot gas well up from its interior, like the roiling of a pan of porridge as you simmer it. As a result, Betelgeuse is constantly changing in brightness: occasionally shining more brilliantly than Rigel, at the other corner of Orion; and sometimes as dimly as Aldebaran in the neighbouring constellation of Taurus.

Over the past few months, though, Betelgeuse has faded more seriously than it has in over a hundred years of scientific measurement. Edward Guinan and Richard Wasatonic of Villanova University in Pennsylvania, who’ve been monitoring Betelgeuse, say the star is now only 40 per cent as bright as it was in September. At the same time, its temperature has dropped by almost 100C, and it’s shrunk to only 92 per cent of its previous size.

But that doesn’t mean – contrary to scare stories in the media – that the core has collapsed, and is about to trigger a supernova. For a start, it would implode in literally a matter of seconds, and the shock wave would rip through Betelgeuse before the outer layers have a chance to fade. So if this dimming were a harbinger of doom, Betelgeuse would have self-destructed weeks ago.

Betelgeuse will go supernova one day, and rival the Full Moon in brightness – but probably not for 100,000 years.

In fact, Guinan and Wasatonic say Betelgeuse has now almost stopped dimming – something we checked roughly by eyeballing the star last night. Their best bet is that the star’s different cycles of brightening and dimming have, by chance, all hit minimum at the same time, producing this superfade.

If Guinan and Wasatonic are right, they predict the star will hit rock bottom on 21 February, and then gradually brighten again. Watch this space, or – even better – watch the sky for yourself!

What’s up

You can’t miss Venus this month, the brilliant Evening Star hanging like a lantern in the western sky after sunset. Venus is brighter than anything else in the night sky apart from the Moon. There’s a lovely sight on the evenings of 26 to 28 February as the crescent Moon moves past the Evening Star.

Coming back to early February, Venus acts as a signpost to another world. Look low on the horizon (preferably with binoculars) to the lower right of Venus, around 6pm, and the brightish “star” is actually Mercury. The innermost planet never strays far from the Sun, so Mercury isn’t easy to spot: this is one of our best chances this year to catch it.

The evenings now are filled with the glorious constellations of winter. Most familiar is Orion (see main story), with his foe Taurus, the Bull, to his upper right. The bovine’s angry eye is marked by red giant star Aldebaran, and the constellation also hosts the beautiful Seven Sisters, the star cluster also known as the Pleiades.

To the lower left of Orion you’ll find the most brilliant star, Sirius, heading up the constellation of Canis Major, the Great Dog. Above is a smaller pooch, Canis Minor, with the star Procyon; and the twin stars of Gemini, Castor and Pollux.

The bright star almost overhead is Capella, a name meaning ‘the little nanny goat’ though – confusingly enough – it’s part of a constellation (Auriga) depicting the celestial Charioteer.

If you’re an early bird, you may spot the second brightest planet, Jupiter, rising in the south-east about 5.30am. Some way to its right you’ll find Mars, with its distinct reddish tinge; while Saturn lies to the left of Jupiter. On the mornings of 18 to 20 February, the crescent Moon glides past these three worlds.

Diary

9 February, 7.33am: Full Moon, near Regulus

10 February: Mercury at greatest eastern elongation

12 February: Moon near Spica

15 February, 10.17pm: Last Quarter Moon

19 February (am): Moon between Jupiter and Mars

20 February (am): Moon between Saturn and Jupiter

23 February, 3.32pm: New Moon

26 February: crescent Moon below Venus

27 February: crescent Moon beside Venus

28 February: crescent Moon above Venus

Philip’s 2020 Stargazing (Philip’s £6.99) by Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest reveals everything that’s going on in the sky this year.

Fully illustrated, Heather and Nigel’s The Universe Explained (Firefly, £16.99) is packed with 185 of the questions that people ask about the Cosmos

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments