Stargazing for October 2017: Watch for the rings

With autumn ahead, the days will be getting darker – the perfect opportunity to see the Orionid meteor shower or spot Saturn’s tipped rings, expected to look more spectacular than they have since 2003

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

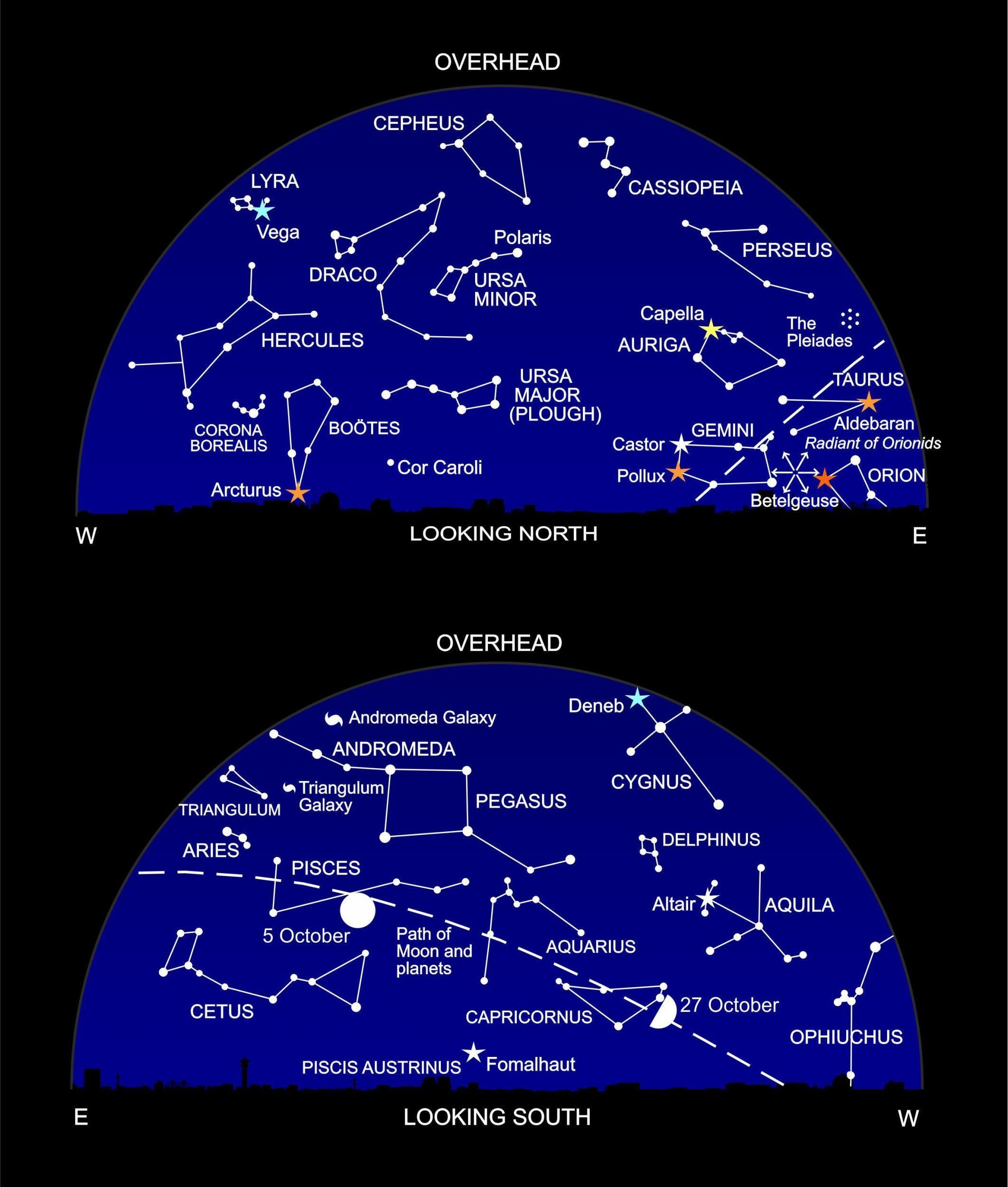

Your support makes all the difference.Autumn is truly with us now: yuck! (sorry, lovers of The Fall). Dying leaves carpet our gardens; it’s cold, misty, wet and miserable; and even the constellation patterns seem to be sulking. Gone are the bright star patterns of summer; and it will be a while yet before the dazzling winter constellations take over. Instead, we have to put up with faint, straggly watery constellations, like Aquarius, Hydra, Pisces and Cetus – the ancient Babylonians worked out that the Sun passed through this part of the sky during their rainy season, from February to March.

The dominant constellation in the sky this month – lording it over the south – is Pegasus. How our ancestors imagined a flying horse in this boring square of stars is beyond us. Likewise, Andromeda: a thin line of stars attached to the top left of Pegasus. Well ... can you see a beautiful princess chained to a rock, about to be gobbled up by a sea monster? But Andromeda makes up for everything by hosting one of the gems of the night sky. It’s the Andromeda Galaxy – the closest large galaxy to our Milky Way. And it’s visible to the unaided eye, even in areas suffering light pollution.

To find it, go to the central star in Andromeda, and follow a short line straight upwards. It’s best seen on a moonless night, and binoculars – or a small telescope – will reveal that it covers an area of the sky four times larger than the Full Moon. It lies 2.5 million light years away, and it’s generally acknowledged as the furthest object you can see with the naked eye. Except – more anon.

The Andromeda Galaxy is a spiral galaxy, like our Milky Way. Unfortunately, it’s presented at such a steep angle to us that we can hardly see the glorious whorls of its spiral arms. But we can measure it up. Our near-neighbour has a population of a trillion stars (we have about 400 billion), and it’s nearly twice as big as our Galaxy.

Like our Milky Way, it’s surrounded by a family of fourteen small satellite galaxies; two are visible through a medium-sized telescope. And its centre conceals a massive black hole – current estimates place it as being 100 million times heavier than the Sun. Which means that there must be a tad of havoc in the core of the Andromeda Galaxy from time to time, when its black hole “feeds” on infalling gas. And talking of havoc: there will be plenty in the future. The expansion of the Universe (caused by the Big Bang) carries most galaxies apart; but not so Andromeda and the Milky Way. They are approaching each other: and in some four billion years’ time, they are set to collide.

It sounds more fearsome than it actually will be. Stars in galaxies are so far apart that collisions will be rare; the two stellar armies will pass each other in orderly ranks. But gravity will cause chaos. The Sun – nearing the end of its life – could be flung out of the melee altogether, or catapulted towards the two supermassive black holes merging at the new galaxy’s centre.

Then – all will go quiet for “Milkomeda”. Having used up its gas resources to make new stars – in a fit of youthful energy – it will become a boring, supergiant elliptical galaxy, made of red giants slowly dying.

Oh, yes – the hanging question as to what is the most distant object visible to the unaided eye? Take that line again from the middle star in Andromeda – and this time go under the line of stars. At the same distance below the line (where you spotted the Andromeda Galaxy above), there’s a fuzzy patch. This is the Triangulum Galaxy: three million light years away.

It’s much smaller than Andromeda, and has a very low surface brightness. But if you have excellent eyesight, and a convenient desert to hand, why not give it a go? A very small number of people have succeeded!

What’s Up?

Let’s start with the highlight of the month - a display of celestial pyrotechnics that’s pre-empting Fireworks Night. The Earth smashes into a trail of debris that Halley’s Comet has left strewn along its orbital path, and the specks of cosmic dust burn up high in our atmosphere as a shower of meteors.

The shooting stars seem to stream outwards from a point near the bright star Betelgeuse, in Orion, and so astronomers fittingly call this month’s display the Orionids. We’re expecting to see most meteors on the night of 20/21 October; but don’t worry if it’s cloudy, as there’ll be reasonable displays a couple of days either side. For the best views, stay up after midnight, as our part of the Earth will then be running full-tilt into Halley’s debris, and the meteors will come thick and fast.

Around midmonth, grab anyone you know with a telescope, and check out that yellowish “star” low in the southwest after sunset. Wow! As you’ll see it’s actually Saturn, looking more spectacular than it’s done at any time since 2003 - its rings tipped up so much that they appear as wide open as they even can when viewed from planet Earth.

Apart from the ringworld, there aren’t any other planets about in the evening sky: wait until 6 am, when brilliant Venus rises in the east. The faint reddish object to its right is Mars; but the Red Planet sulks at only one-hundredth the brightness of the Evening Star. And don’t forget to put your clocks back in the early morning of 29 October. The end of British Summer Time may make us think of cosy nights in; but don’t forget the earlier dark nights will also be beckoning us outside to view the glorious of winter stars!

Diary

5 October, 7.40pm Full Moon

12 October, 1.25pm Moon at Last Quarter

16 October Saturn’s rings widest open

19 October, 8.12pm New Moon

20/21 October Maximum of Orionid meteor shower

27 October, 11.22pm Moon at First Quarter

29 October, 2am End of British Summer Time

For a preview of all that’s up in the sky next year, check out Heather Couper and Nigel Henbest’s latest book: Philip’s 2018 Stargazing

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments