Some choice words for diabetes

The Bigger Picture campaign uses spoken-word poems and music videos to highlight the impact of type 2 diabetes on communities

Type 2 diabetes was once known as adult-onset diabetes. But now that term is outdated: increasingly it is a condition that begins in childhood.

Between 2000 and 2009, the rate of type 2 diabetes in American children jumped more than 30 percent – and it is climbing especially fast among children from poor and minority families. The prevalence of type 2 diabetes doubled in the past decade among black children and tripled among Native American children. Black and Hispanic children have eight times the risk of developing the disease compared with others.

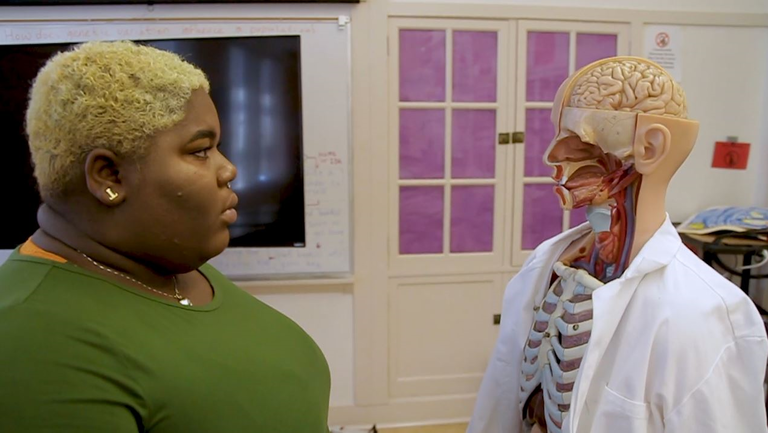

Faced with these dire numbers, health experts and arts educators have teamed up to try a novel approach to preventing the condition in young people. The campaign, called The Bigger Picture, aims to get teenagers and young adults to view the diabetes crises in their communities not just as a medical problem related to poor diet and a lack of exercise but as a social justice problem tied to stress, poverty, violence and limited access to healthy and affordable foods.

At its core, the program, created by the University of California, San Francisco School of Medicine and not-for-profit arts group Youth Speaks, uses art to confront obesity and diabetes in youth. Poet mentors and doctors have been conducting workshops in poor communities, where they educate high-risk youth about the epidemic and provide a platform for them to create spoken-word poems to express how diabetes and obesity affect them. The young people perform their poems live at public high schools and turn them into music videos filmed in their neighbourhoods.

A recent journal article highlights some of the latest spoken-word videos, which were released on The Bigger Picture website and spread via social media. One, entitled “The Longest Mile,” by Tassiana Willis, a young poet from Oakland whose family has been hit hard by diabetes, describes growing up in a poor community where family trips to fast food outlets were a “tragic tradition” that ultimately led to obesity.

“This is about how I starve myself before blood work, praying it doesn’t pick up the candy from my last time of the month,” she says in her poem. “This is my battle between diet and dialysis, about being stuck between two Burger Kings, and never having it your way.”

The videos contain rich and at times startling detail about life in communities overrun by gun violence, poverty and food insecurity. They tell the stories of families where amputations, strokes and other complications of diabetes are the norm. One video, “Perfect Soldiers,” is written and performed by Gabriel Cortez, a young poet who laments seeing his relatives struggle with diabetes, a condition, he says, that “is as common in our family as heartburn”. He talks about his grandfather, a military veteran who consumes multiple sugary drinks daily despite suffering from diabetes.

“At 66, we are scared that another stroke could do what no war ever could and cut him to the ground,” Gabriel says in his video poem. “He drinks, like aunt Maritza didn’t lose both of her legs to diabetes last year, like half of our neighbourhood doesn’t look like the emergency ward of a hospital, like he hasn’t seen the pictures: how it is impossible to tell the difference between a roadside bomb victim, and someone who just forgot to take their insulin.”

The program is in part the brainchild of Dr Dean Schillinger, a co-founder of the UCSF Center for Vulnerable Populations and a primary care doctor at Zuckerberg San Francisco General Hospital. Schillinger began his career at the hospital in the 1990s in the throes of the AIDS crisis, when nearly half of his patients were dying of the disease. Schillinger witnessed the number of cases plunge as activists, public health experts and the medical and scientific communities came together. But then the obesity crisis began and a new wave of disease flooded San Francisco General.

“The AIDS ward is now a diabetes ward,” Schillinger said. “Maybe one in 15 patients had diabetes when I started 25 years ago. Now one in two of my clinic visits are with patients who have diabetes.”

Between 2008 and 2013, Schillinger served as chief of the Diabetes Prevention and Control Program for the California Department of Public Health. Looking at maps of San Francisco, he said, he noticed that diabetes hospitalisation rates differed ten-fold from one neighbourhood to the next, driven by factors such as income, education, segregation and sugary drinks consumption. While the public discourse around type 2 diabetes tended to revolve around “shame and blame” – the idea that people who develop the disease knowingly make bad choices –Schillinger looked at these diabetes hot spots and began to think of the crisis as a social and environmental problem.

Many of his patients live in poor neighbourhoods awash in fast food chains and billboards advertising junk foods. With limited incomes, they are often forced to purchase the cheapest, highest-calorie meals to feed their families, which often means choosing packaged goods and fast foods instead of fresh produce. Poverty and the threat of violence bring chronic stress. “I have many patients who say they will not let their kids go outside and play after school or after dark because they’re afraid of gangs and shootouts,” he said.

One day he attended a Youth Speaks event where he saw an overweight 16-year-old girl perform a poem about her body image issues, her addiction to junk food and the diabetes that runs in her family.

“She was describing how she was eating cupcakes even as she wheeled her aunt who had diabetes and kidney failure into her dialysis appointment,” he said. “It was basically a food addiction poem in the context of the diabetes epidemic, with the addiction being a consequence of poverty, stress and insecurity. There were so many forces acting on this child that the pathways inevitably led to diabetes.”

A light bulb went off for Schillinger and for James Kass, then executive director of Youth Speaks. With funding from the US-based National Institutes of Health, the UCSF Diabetes Family Fund and other sources, they started The Bigger Picture project in San Francisco and spread it to seven other regions across California. The spoken-word poems have been performed to more than 10,000 high school students and viewed 1.5 million times on YouTube.

The Bigger Picture team hopes to conduct a study to see if the campaign has any long-term impact on obesity or diabetes rates. In the meantime, they say their goal is to change the national conversation about type 2 diabetes. They say the young poets are removing the stigma around the disease and calling attention to the fact that it is often impossible for people to make good choices when their options are limited.

“To make healthy choices, you’ve got to have healthy choices to make that are accessible and affordable,” said Natasha Huey, a poet and project manager for The Bigger Picture. “I would really challenge folks to take $5 and walk through the neighbourhoods that a lot of our young folks are coming from and feed themselves healthily. It isn’t easy, and that’s why this isn’t a conversation about individual choices – it’s about systems.”

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments