Scientists discover mile-high mountains towering deep under the sea

The ocean floor is still little understood

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Researchers have only just discovered thousands of new mountains across Earth – some towering almost a mile high – because they are hidden in the depths of the ocean.

The findings are a glaring reminder of how little is known about the seafloor – a fact exemplified in the recent search for the missing MH370 aircraft, which is believed to be off the coast of Australia.

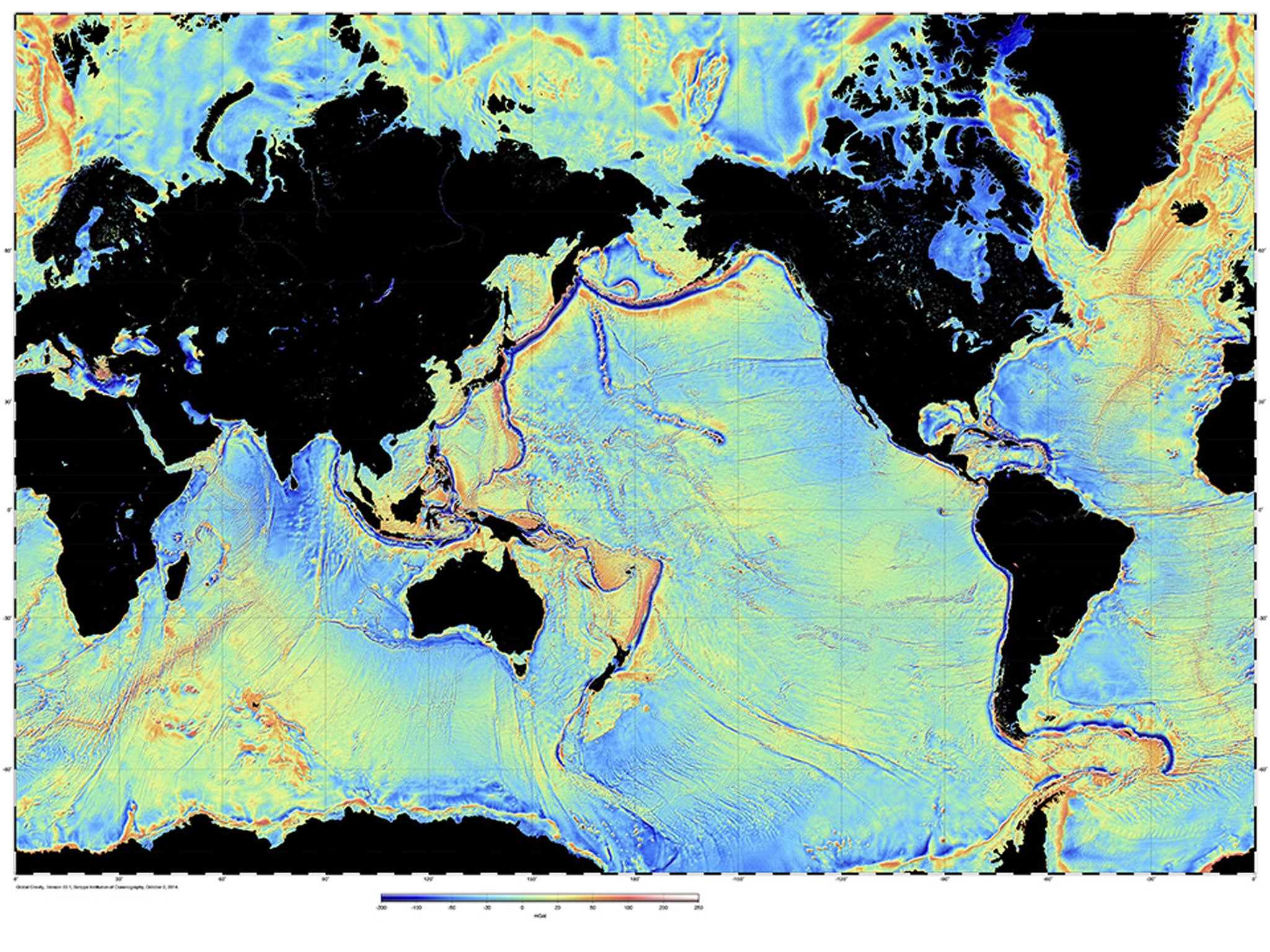

To make their findings, scientists used radar satellites to pinpoint where the mountains are positioned under water.

Professor Dave Sandwell of the Scripps Institution of Oceanography told BBC News that the radars had previously spotted mountains higher than 2km (1.2 miles), as they protrude closer to the surface.

But a new dataset has revealed mounts that are 1.5km (0.9miles) tall – a significant find.

“That might not sound like a huge improvement but the number of seamounts goes up exponentially with decreasing size.

"So, we may be able to detect another 25,000 on top of the 5,000 already known," he explained.

Among the findings made by oceanographers are an extinct ridge where the seafloor spread apart to help open up the Gulf of Mexico about 180 million years ago; and two halves of another ridge that became separated around 85 million years ago when Africa rifted away from South America.

It is so difficult to understand the ocean floor because of the properties of saltwater. As it is opaque, techniques that scientists often use to map mountains on land are rendered useless.

And while echosounders carried on ships can create high-resolution maps of the ocean, by bounding waves off terrain, only 10 per cent of the oceans have been surveyed in this way due to the sheer effort involved.

Instead, scientists have for decades used satellites fitted with radar altimeters, which can plot the shape of the ocean according to how the water is controlled by gravity are around different terrain.

The research, published in the journal ‘Science’, harnessed these tried and tested methods with newer spacecraft: Jason 1, and CryoStat – which was in fact intended to measure the thickness of polar ice.

The new information will help both fisherman and conservationists, as wildlife tend to mass around these topographic high points. It is also vital in understanding climate change, and how heat is transported in the ocean.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments