Science news in brief: From a robot with a light touch to a caterpillar that can see with its skin

And a roundup of other news from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Humans dominated Earth earlier than previously thought

Humans substantially altered the planet much earlier than previously thought, a worldwide collection of archaeological experts say. By 3,000 years ago, the experts write in Science magazine, the planet had been “largely transformed by hunter-gatherers, farmers and pastoralists”.

People farmed, burned forests and grazed their goats, sheep and cattle. By about 1000BC, with Mayan civilisation on the rise in Mesoamerica and the Zhou dynasty beginning in China, what the authors describe as intensive agriculture, or continuous cultivation of the land, was “common in most regions where it is still practised today”.

The results vary for different farming practices and different regions, says Erle Ellis, a geographer and environmental scientist at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County, and a designer of the ArchaeoGlobe project, as the research effort is called. But, he says, it is clear that the information pushes back the onset and spread of major human change to the global environment earlier than previously thought, sometimes by 1,000 years or more.

“What we’re showing,” says Lucas Stephens, who helped design and administer the survey of 250 or so archaeologists on which the report is based, “is that there is a deep history of this, going back further than what earth scientists currently recognise.” Stephens, now at the Environmental Law and Policy Centre in Chicago, organised the survey while he was at the University of Pennsylvania and the University of Maryland, Baltimore County.

The report seems to be a first. Archaeologists tend to be local or regional, devoted to particular sites and time periods. “There has never been a real effort to put together an empirical global land-use history,” Ellis says.

Because information about the past informs predictions of global change in the future, in terms of climate and land use, hard evidence of past land use is invaluable, experts say. “It’s an important paper,” says John Williams, a palaeoecologist at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, who was not involved in the project.

He says it “establishes clearly” that the Anthropocene, the age of human dominance of the planet’s ecological and climate systems, did not begin just a few hundred years ago. “You can trace it back thousands of years,” he says.

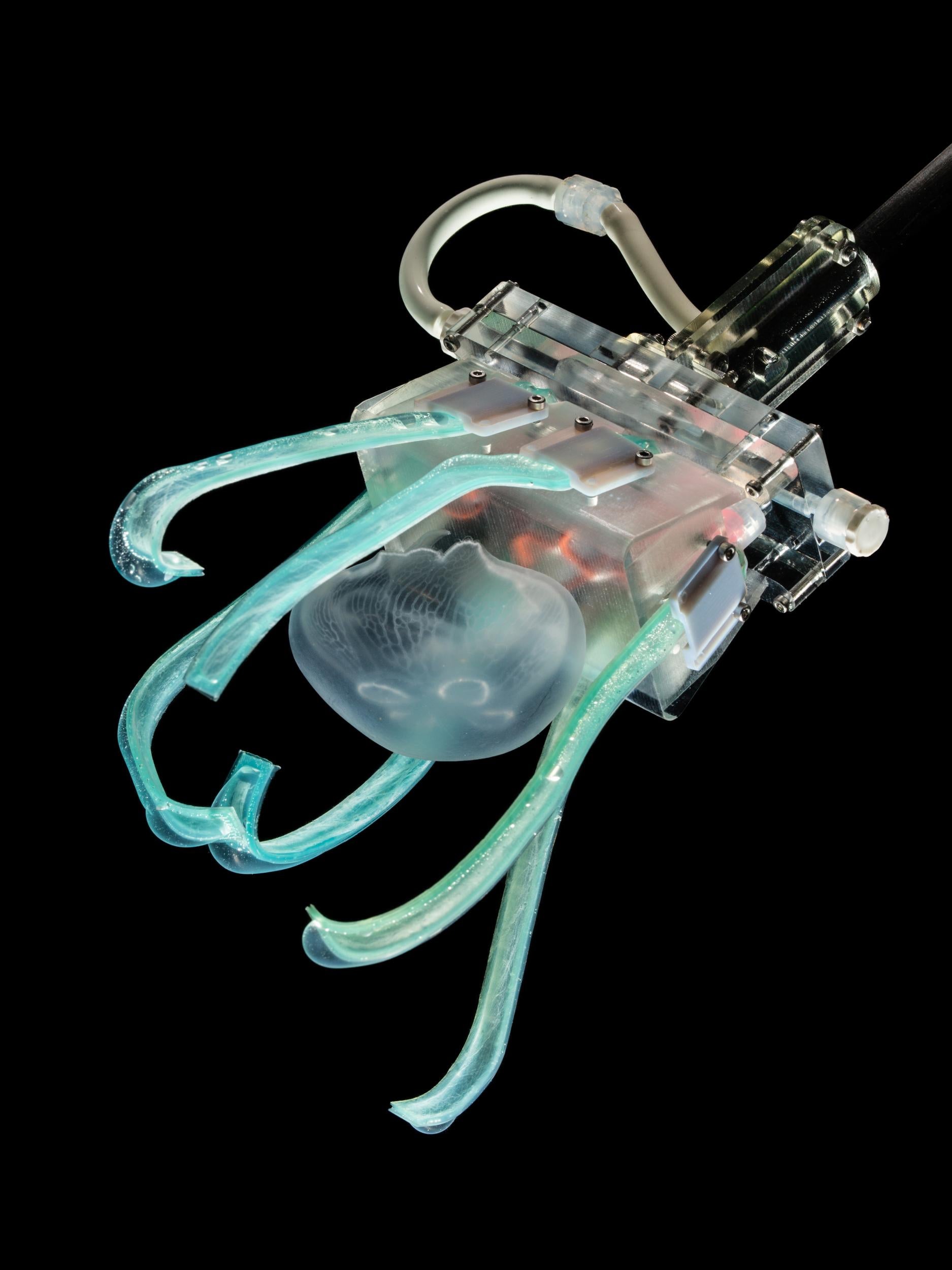

A robot with noodle-like fingers helps handle soft jellyfish

It’s tough for a marine biologist to study deep-sea creatures in their natural habitat.

Jellyfish and squid that live a mile or two underwater dwell beyond the range of scuba diving scientists, who must rely on submarines to explore the near-complete darkness at those depths. Once in a while, detritus samplers and other collection tools attached to submersibles can capture the diaphanous animals. But the delicate creatures are at risk of getting stuck in the sampler or destroyed on their way to a lab on dry land.

That’s why David Gruber, a marine biologist at the City University of New York, and a team of engineers are developing soft robots capable of gently grasping live jellyfish and studying them without harming the specimens.

“I always felt that it was a little strange for me as a marine biologist to have to kill the animals that I love and study,” Gruber says. “I wanted tools that were more gentle, that were able to grasp jellyfish but not hurt them, and that would allow me to swab the creatures and do different things.”

To create a robot strong enough to work in the deep sea, yet gentle enough to handle gelatinous jellyfish that are about 95 per cent water, the scientists came up with a six-fingered gripper that could open and close around the animals. They describe their design in the journal Science Robotics.

Each of the six noodle-like fingers is composed of thin strips of silicone with a hollow channel inside. The inside edges of the fingers have a stiffer nanofibre coating that controls how they curve. They are attached to a 3D-printed rectangular palm in such a way that they can be removed individually and replaced if they start to become arthritic.

A switch at the back of the gripper fills the channels inside the silicone fingers with water, forcing them to curl shut in the direction of the nanofibre coating. This helps maintain an ultra-gentle grip; the fingers exert less than one-10th of the pressure that a human eyelid exerts on the eye.

“When the fingers close, they’re almost cradling the animal, giving it a nice, gentle hug,” says Nina Sinatra, a mechanical engineer and a former graduate student at the Wyss Institute for Biologically Inspired Engineering at Harvard, who helped design the robot.

The robotic gripper can open and close about 100 times before it starts to show signs of wear. That’s enough to sample plenty of deep-sea creatures on a research mission, but scientists hope to continue to refine the tool’s robustness and capabilities, Gruber says.

Adding cameras and sensors to the gripper could help make it a portable underwater laboratory. Scientists could steer it towards deep-sea jellyfish of interest using a joystick, grab a specimen to study, scan its body, swab for DNA and record physiological responses before letting the creature go.

“It’s important to be gentle as we explore new frontiers,” Gruber says.

Hanging out with humans makes this seed-eating bird bad at its job

According to a new study, members of a particular New Zealand bird species, weka, that spend time around humans become worse at a crucial task: seed dispersal. In the woods, weka roam around searching for food. But the ones that spend time in campsites and picnic areas tend to lurk, waiting for the snacks (and seeds) humans bring.

The researchers used GPS trackers to measure how far weka from a few different areas travelled over the course of two weeks. Some of these study subjects were campsite regulars, while others lived in the forest, away from humans.

On average, the campsite-dwelling birds carried seeds (and discharged them from their systems) only about half as far as their forest-roaming peers.

These marsupial drop dead after mating

Kalutas live fast and die young – or, at least, the males do. Male kalutas, small mouse-like marsupials found in the arid regions of northwestern Australia, are semelparous, meaning that shortly after they mate, they drop dead.

This extreme reproductive strategy is rare in the animal kingdom. Only a few dozen species are known to reproduce in this fashion, and most of them are invertebrates. Kalutas are dasyurids, the only group of mammals known to contain semelparous species. Around a fifth of the species in this group of carnivorous marsupials – which includes Tasmanian devils, quolls and pouched mice – are semelparous and, until recently, scientists were not sure if kalutas were among them.

These caterpillars can ‘see’ colours with their skin

If you’ve never seen a peppered moth caterpillar, don’t feel bad: they’re experts at blending in. Each caterpillar mimics the twig it perches on, straightening its knobbly body into a sticklike shape.

It also changes its hue to match the twig’s colour, whether birch white, willow green or dark oak brown.

They’re so good at this, in fact, that they can do it blindfolded – literally. According to a paper published in Communications Biology in early August, the caterpillars sense the colour of their surroundings not only with their eyes, but also with their skin.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments