Science news in brief: From a Jurassic mystery to the genetics of sleep

Plus a roundup of other news from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.How did an ancient sea turtle end up under a dinosaur’s foot?

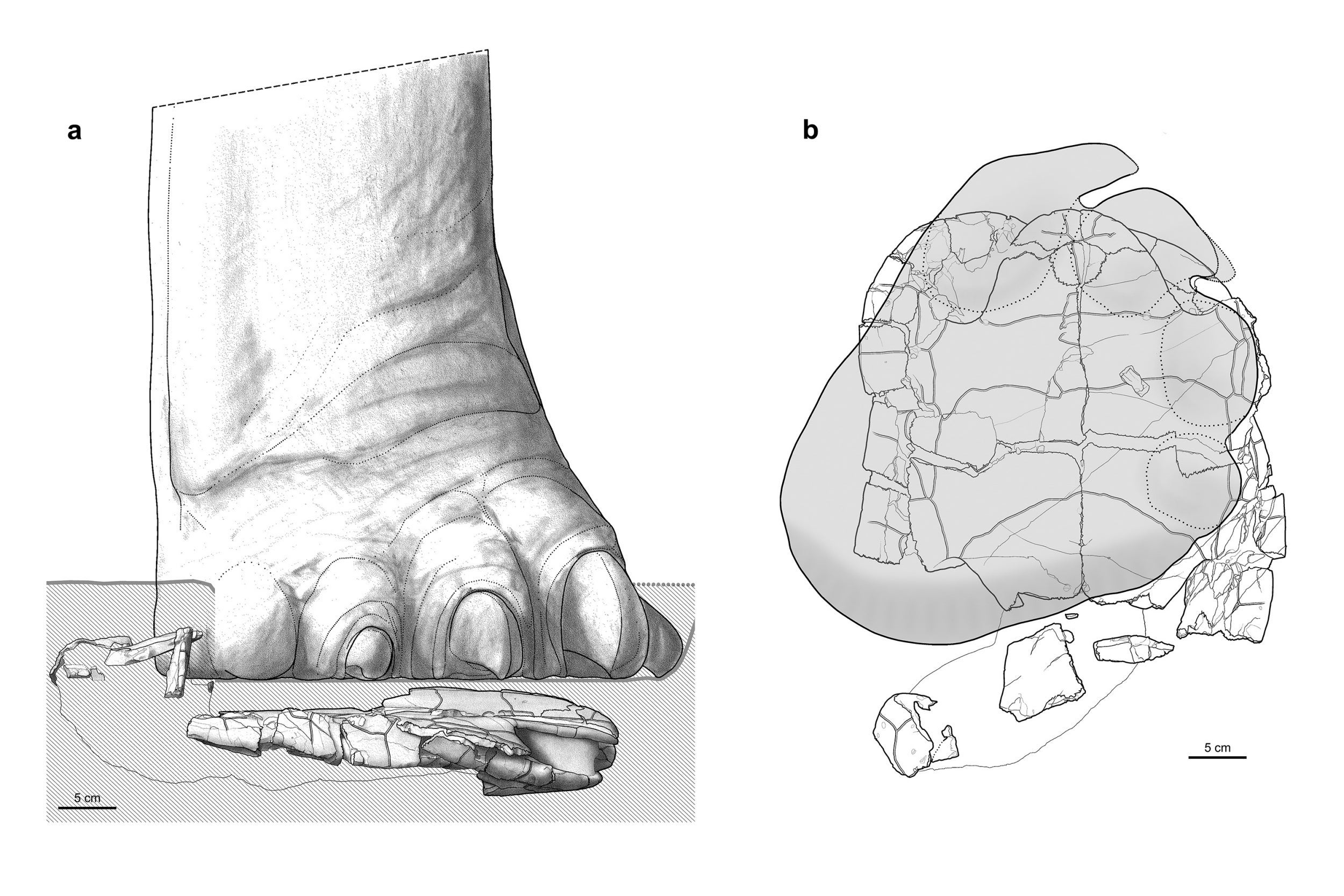

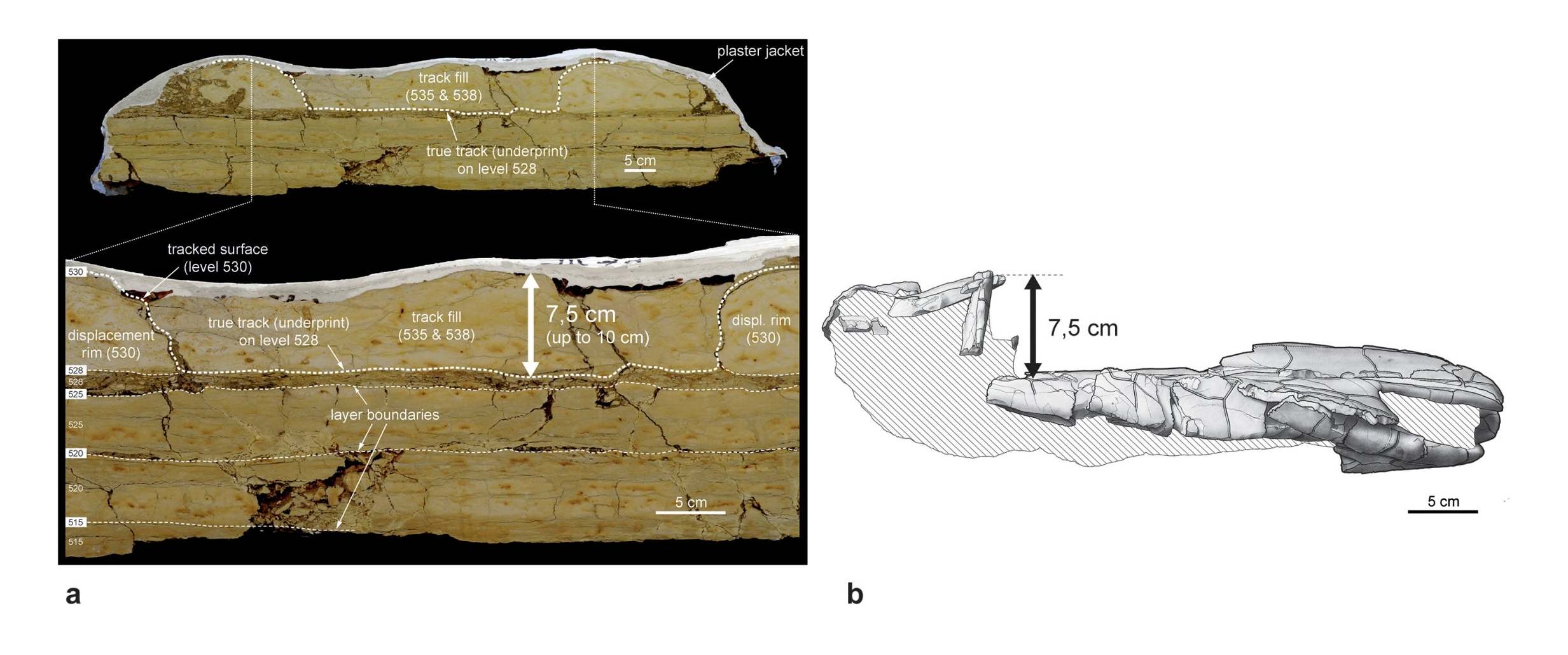

One day towards the end of the Jurassic Period, a long-necked, long-tailed sauropod dinosaur about the size of an elephant lumbered over a tidal flat in what is now Switzerland, leaving footprints wider than beach balls.

Maybe it heard a crunch. Because much later, near these footprints, a team of palaeontologists found a damaged carapace from an extinct sea turtle species called Plesiochelys bigleri halfway pressed into the sediment. They argue in a new study that animal was stepped on.

“The evidence is pretty clear,” says Daniel Marty, a palaeontologist at the Natural History Museum in Basel, Switzerland, who participated in the study. “It’s kind of a funny thing, and it also shows that these two animals were in the same palaeoenvironment.”

Crushed seashells are sometimes found in dinosaur tracks, and scientists also find dinosaur bones scoured with marks where other dinosaurs walked over them. But cases where footprints and damaged bones appear together are rare, the team says.

The turtle shell was found during an extensive dig in the Jura Mountains, which gave the Jurassic Period its name.

More recently there have been recorded cases of elephants crunching turtles underfoot, offering a modern analogy. But large predators like jaguars can also break apart a sea turtle shell in a way that can make it look as if it has been crushed, says Tristan Stayton, an evolutionary biologist at Bucknell University who studies the structural properties of turtle shells, among other things, but was not involved in the discovery of this particular shell.

Another explanation, says Jordan Mallon, a palaeontologist at the Canadian Museum of Nature who also was not involved in the study, is that the fossil was simply crushed under the weight of the rocks above it over the millions of years it was buried. “I think they tell a plausible story, but it’s not a dead ringer,” he says.

Still, “it’s important to document fossils like this where you can try to show two species lived together”, Mallon says. “It’s only by doing that that we’re able to reconstruct ancient ecosystems.”

Can genetics explain why some people thrive on less sleep?

Brad Johnson and two of his siblings never sleep more than six hours a night. Researchers who learned of their sleeping habits wondered whether there was something about the genetics of the siblings that help explain how sleep works for the rest of us

Dr Louis Ptacek, a California neurologist, and his colleagues identified a gene mutation that shows up in every naturally short-sleeping member of the family. When the scientists took the mutated version of the gene and put it in lab mice, the mice needed about an hour less sleep a day than their siblings that did not have the gene.

The researchers determined that the gene, ADRB1, has a direct bearing on how much sleep people need. Their findings could be used to design therapies to help people with sleep problems.

The gene that Johnson shares with his siblings affects communication among certain brain cells.

White barn owls thrive when hunting in bright moonlight

When the moon hits your eye like a big pizza pie, it may not be amore at all, but a ghostly white barn owl about to kill and eat you. If you’re a vole, that is.

Voles are a favourite meal for barn owls, which come in two shades, reddish-brown and white. When the moon is new, both have equal success hunting for their young, snagging about five voles in a night. But when the moon is full and bright, the reddish owls do poorly, dropping to three a night.

Barn owls with white faces and breasts do as well as ever, however, even though they should be more easily spotted than their reddish relatives when the lunar light reflects off their feathers.

They may well be more easily seen, but it doesn’t matter because of the behaviour of their prey. Voles have two responses to owl sightings. They freeze, and hope the owl doesn’t see them. Or they run. But when they see a white owl in bright moonlight, the terrified rodents act like deer caught in headlights and freeze for up to five seconds longer than they do for a reddish-brown barn owl. Luis M San-Jose and Alexandre Roulin, both scientists in Switzerland, reported in a new study that they had expected the white owls to do worse.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments