Science news in brief: From flushing contact lenses to increased sales in giraffe parts

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Before flushing contact lenses, consider where they’re going

If you throw out your contact lenses every day or so, you’re not alone – more than 45 million people in the United States wear contacts, and many of them use disposables.

But if they are not tossed out correctly, contact lenses may have a dark side.

Research presented at the American Chemical Society’s meeting in Boston showed 20 per cent of more than 400 contact lense wearers randomly recruited in an online survey, flushed their used contacts down the toilet or washed them down the sink, rather than putting them in the rubbish.

When lenses arrive at a wastewater treatment facility they do not biodegrade easily, the researchers report, and may fragment and make their way into surface water. There they can cause environmental damage and may add to the growing problem of microplastic pollution. A 2015 study found 93,000 to 236,000 metric tons of microplastic in the ocean.

Filters keep some non biological waste out of wastewater treatment plants, said Rolf Halden, director of the Center for Environmental Health Engineering at Arizona State University, and Charles Rolsky, a graduate student and the study’s lead author. But contacts are so flexible they can fold and get through. The researchers interviewed workers at such facilities who confirmed they had spotted lenses in waste.

Next, the team submerged contacts in chambers where bacteria were used to break down biological waste at a treatment plant. They found that even after seven days of exposure lenses appeared intact, though lab analysis detected small changes in the material.

Searching around 9lb of treated waste, Rolsky and a colleague found two fragments of contact lens, implying that while micro organisms might not make much of a mark, physical processing may break them into pieces.

After processing, treated waste is often spread on fields and if fragments of contacts are in the mixture, they or the substances they’ve picked up may be washed by rain into surface water, the researchers conjecture.

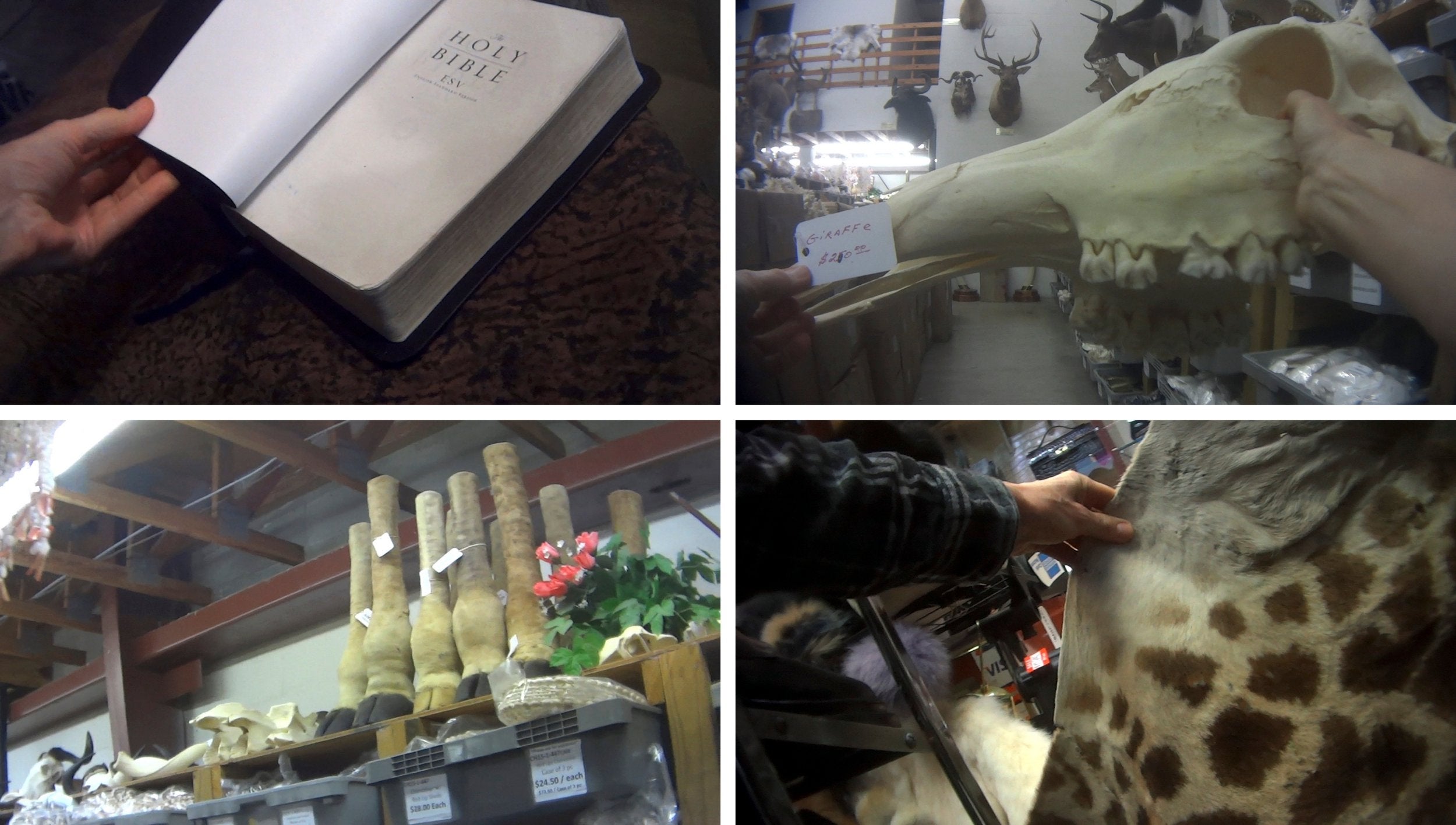

Giraffe part sales are booming in the US, and it’s legal

At a time when the wild giraffe population is plummeting, the sale of products made with giraffe skin and bone is booming.

According to the Humane Society of the United States and its international affiliate, more than 40,000 giraffe parts were imported to the US from 2006 to 2015 to be made into expensive pillows, boots, knife handles, bible covers and other trinkets.

The sale of such products is legal but the organisation argues restrictions are needed. Along with other advocacy groups, it has petitioned the US Fish and Wildlife Service to provide such protection by listing giraffes as an endangered species.

It is issuing a report “to ramp up the pressure and show the public the true nature of the giraffe trade in the US, and show the administration that the public loves giraffes and really wants their government to take action to protect this animal,” said Adam Peyman, manager of wildlife programmes and operations for the Humane Society International.

In 2016, a study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources, determined the worldwide giraffe population had fallen from 150,000 to 100,000 since 1985. Giraffes face two main threats, the report found: habitat loss and poaching by locals in search of bushmeat.

Trophy hunting seems to be the primary reason for the animals arriving in the United States, but isn’t driving the animals to extinction, Peyman said. Any market for giraffe products puts more pressure on the species.

The market for giraffe parts, Peyman said, may have inadvertently been increased by a ban on importing some elephant products, upheld by the Trump administration late last year.

An investigator with the society’s US organisation went undercover to 21 locations to track giraffe sales and to talk to sellers.

The investigator found the stuffed body of a juvenile giraffe selling for $7,500 (£5,820), according to the Humane Society, and a pillow made with an animal head, intact down to its eyelashes.

On bible covers selling for $400, and equally expensive boots, the hair is removed from the hide – so it is not evident the source is a giraffe.

For pregnant dads who stray, there are plenty of other pipefish in the sea

Pipefish, along with their cousins sea horses and sea dragons, defy convention in love and fertility. In a striking role reversal, fathers give birth instead of mothers.

During courtship, females pursue males with flashy ornaments or elaborate dances and males tend to be choosy about which females’ eggs they’ll accept. Once pregnant, the gender-bending fathers invest heavily in their young, supplying embryos with nutrients and oxygen through a setup similar to the mammalian placenta.

But the investment may also be cruelly conditional, according to a new study in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. Studying pipefish, scientists found evidence pregnant fathers spontaneously abort, or divert fewer resources to their embryos, when faced with the prospects of a superior mate – in this case, an exceptionally large female.

The researchers named their finding the “woman in red” effect, after the 1984 Gene Wilder film about a married man’s obsession with a woman in a red dress.

The reported effect is an interesting instance of sexual conflict, ubiquitous among animals, said Sarah Flanagan, a pipefish expert at the University of Canterbury in New Zealand.

Previous research had found pipefish fathers invest less in pregnancies from small females if they have previously bred with larger females.

At the risk of anthropomorphising, Flanagan said, it’s as if male pipefish are thinking: “I’ve done better in the past.”

In their study, scientists bred male black striped pipefish with large females, then kept each father-to-be in a tank partitioned from a new female of equal size, a new female much larger in size or the original mate.

Males in the “woman in red” group – exposed to a new, “sexier” female – had the highest rates of abortion and shortest pregnancies. They also birthed smaller offspring, some of which had abnormalities.

It seems these fathers stopped investing in their offspring to save up for a better brood, said Jacinta Beehner, an associate professor of psychology and anthropology at the University of Michigan, who studies reproductive strategies in primates.

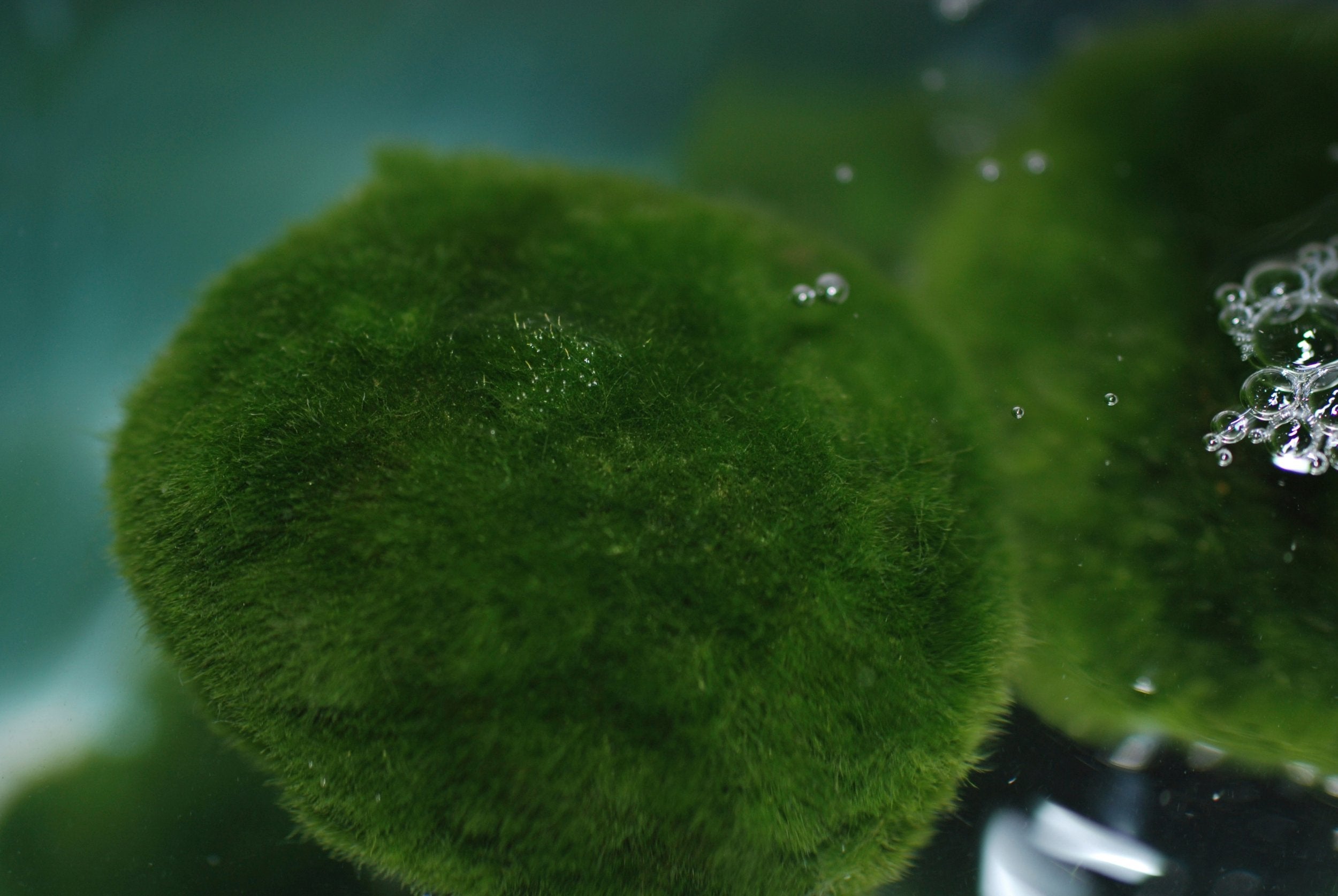

Green orbs that float by day and sink by night

Moss balls, lake balls, Cladophora balls, marimo – whatever you call them, they’re strange and they’re beautiful.

These mysterious green orbs occupy cool lakes in the northern hemisphere in places like Scotland, Iceland and Ukraine. In Japan, they are a protected species and a national treasure.

Under certain conditions, marimo form when a type of algae bind together and roll in currents at the bottom of shallow lakes, collecting in large colonies. Sometimes the orbs – which can be nearly 1ft in diameter – rise to the surface during the day and sink back down at night.

Marimo contain many mysteries. But now at least one has been solved. In a paper published recently in Current Biology, scientists at the University of Bristol described how the freshwater phenomenon floats and sinks. The algae regulate photosynthesis with a biological clock, and in the process release oxygen bubbles that carry them toward the sun.

Carl Linnaeus first collected samples of the spheres in Sweden in 1753 but they weren’t named “marimo” until fellow botanist Takuya Kawakami found them along Lake Akan in Hokkaido, Japan more than a century later. Now they are a protected national treasure in the country.

Collecting them from Lake Akan is otherwise prohibited but people keep marimo – man-made or collected elsewhere – as aquarium pets, which is how they captured the attention of Dora Cano-Ramirez, lead author of the Current Biology paper.

After purchasing a marimo she noticed bubbles covered them only at some times of the day. During the day, she observed, a few moved to the top of the tank. Because she had studied how biological clocks control photosynthesis in land plants, she wondered if the same kind of processes might be at play in her light-harvesting algae. She took her idea to Antony Dodd, a biologist and head of her lab.

If land plants use biological clocks and some aquatic creatures that live symbiotically with sun-loving algae try to maximise light exposure, Dodd theorises it possible floating may allow marimo to capture more light. Sinking may also protect them from cold surface water or ice, he said.

Going to the moon? Remember to take your skates

There is almost certainly ice water on the moon, hiding in the cold, dark places near the north and south poles, a new study claims.

Scientists had already thought there was water up there, and now we have some of the most definitive proof. It appears such ice – very muddy and mixed with a lot of lunar dust – exists in craters where direct sunlight does not reach it.

But we still do not know how deep it goes, or how exactly it got there.

The authors of the study, published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, say the findings are exciting because they call for further exploration of our rocky satellite. The ice could even be a resource for human visitors – perhaps as drinking water, or even to make rocket fuel.

Shuai Li, the lead author and a planetary scientist at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, said despite decades of lunar research, scientists have had trouble exploring the polar regions of the moon, in part because the craters are so dark.

“So there aren’t too many measurements,” he said. “But a lot of things are going on there.”

Researchers estimate the exposed ice covers only 3.5 per cent of the craters’ shadowy areas. They don’t know whether the water runs deep, like the tips of buried icebergs, or is as thin as a layer of frost.

The data used by Li and his team was not new. It had been collected by NASA’s Moon Mineralogy Mapper, which hitched a ride on Chandrayaan 1, India’s first lunar probe, in 2008 and 2009.

The instrument was able to map most of the moon’s surface, but data from the permanent shadows – inside some craters near the poles – was patchy and hard for researchers to work with.

So Li and his team peered into dark craters using traces of sunlight that had bounced off crater walls. They analysed the spectral data to find places where three specific wavelengths of near infrared light were absorbed, indicating ice water. The researchers also performed rigorous statistical analysis to ensure their results were uncorrupted by coincidental anomalies or instrument errors.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments