Science news in brief: Scientists find a graveyard of continents underneath the Antarctic ice

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

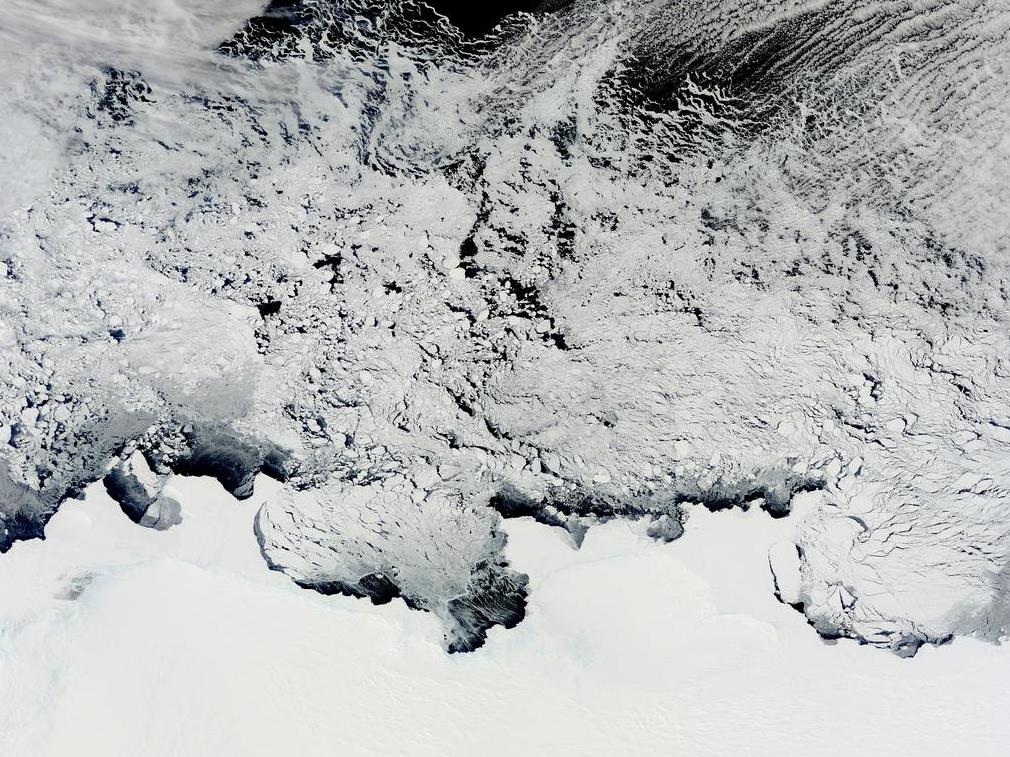

Scientists find graveyard of continents beneath the Antarctic ice

The eastern section of Antarctica is buried beneath a thick ice sheet. Some scientists simply assumed that under that cold mass there was nothing more than a “frozen tectonic block”, a somewhat homogeneous mass that distinguished it from the mixed up geologies of other continents.

But with the help of data from a discontinued European satellite, scientists have now found that East Antarctica is in fact a graveyard of continental remnants. They have created stunning 3D maps of the southernmost continent’s tectonic underworld and found that the ice has been concealing the wreckage of an ancient supercontinent’s spectacular destruction.

The researchers, led by Jörg Ebbing, a geophysicist at Kiel University in Germany, reported their discovery recently in Scientific Reports.

The findings relied on data from the Gravity Field and Steady-state Ocean Circulation Explorer (GOCE) satellite, which orbited Earth just 155 miles above the surface until late 2013, when it re-entered the atmosphere at the end of its mission. Called the “Ferrari of space”, this sleek instrument could measure the gravitational fields weaving through Earth’s crust and mantle.

Kate Winter, who studies Antarctica’s glaciers at Northumbria University and was not involved in the study, said the GOCE satellite data “helped us to piece the supercontinent back together in magnificent detail”.

GOCE’s eye revealed that East Antarctica is a jigsaw puzzle of at least three geological titans named cratonic provinces. Cratons are stable rocky cores of continents that survived hundreds of millions of years of destructive action by Earth’s plate tectonics.

One craton has geological similarities with some of Australia’s bedrock, while another resembles part of India’s. The third is an amalgamation of pieces of old seafloors.

Fausto Ferraccioli, a senior geophysicist at the British Antarctic Survey and co-author of the study, said that “how and when all these provinces came together to make up East Antarctica as we see it today is still a matter of speculation and debate.”

The pieces may have been assembled as far back as 1 billion years ago, when the supercontinent Rodinia was built, or as recently as 500 million years ago, when another supercontinent, Gondwana, came together. Either way, what has been found beneath Antarctica is part of what was left after Gondwana’s dissolution, around 160 million years ago.

An asteroid leaves a great depression in Greenland

Buried beneath a half mile of snow and ice in Greenland, scientists have uncovered an impact crater large enough to swallow the District of Columbia.

The finding suggests that a giant iron asteroid smashed into what is today a glacier during the last ice age, an era known as the Pleistocene Epoch that started 2.6 million years ago. When it ended only 11,700 years ago, megafauna such as sabre-toothed cats had died out while humanity had inherited the Earth.

The discovery could lead to insights into the ice age climate, and the effects on it from the eruption of debris that would have resulted from such a cataclysmic collision.

“This is the first impact crater found beneath one of our planet’s ice sheets,” said Kurt Kjær, a geologist at the Centre for GeoGenetics at the Natural History Museum of Denmark and lead author of the study, published recently in the journal Science Advances.

For three days in May 2016, his team flew over the crater in a German aeroplane with an ice-penetrating radar, drawing imaginary grid lines across the surface.

John Paden, a radio-glaciologist at the University of Kansas, operated the radar on the flight. Every second it sent 12,000 radio wave pulses down into the ice, reflecting off the ice layers and allowing the team to measure the thickness, structure and age of the ice sheet.

The aerial survey confirmed there was a huge pit with an elevated, circular rim and uplifting structures in the centre, all telltale signs of an impact crater. The team’s analysis showed that the crater, dubbed Hiawatha, was nearly 1,000 feet deep and 20 miles in diameter, placing it among Earth’s 25 largest impact craters, although much smaller than the 90-mile crater left by the dino-busting Chicxulub impact.

“Once you start looking for structures beneath the ice that look like an impact crater, Hiawatha sticks out like a sore thumb,” said Joseph MacGregor, a glaciologist at Nasa Goddard Space Flight Centra in Maryland and a co-author of the study.

The mountain lion who couldn’t outrun a California wildfire

On the morning of 9 November, a wildfire broke out of a small area outside Los Angeles, jumped Highway 101 and ignited the jagged hills of the Santa Monica Mountains. In its path were thousands of homes and residents, and a mountain lion named P-74.

It was the last day P-74 was seen alive. While the wildfire, known as the Woolsey Fire, raged through the slopes and canyons over the next two weeks, scorching more than 1,500 buildings and killing three people, park rangers in the Santa Monica Mountains searched for GPS signals from about a dozen mountain lions constantly tracked there. All of them were eventually located alive except for P-74, a roughly one-year-old male and the newest member of the group.

Rangers in the Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area, a vast area of trails and parks on federal land overlooking the Pacific Ocean, now confirm that P-74 likely died in the blaze. His GPS collar last sent a signal at 1pm Pacific time on 9 November, but failed to register at the next automatic check-in, at 5pm that same day.

“We never got another point after that,” Seth Riley, the wildlife branch chief at the recreation area, said. “The fire came through that evening in his area.”

With the help of firefighters, Riley and other park officials searched the seared terrain, including the exact area of P-74’s last known location, for any signs that he survived. But they came up with nothing, leading Riley to conclude that P-74 was trapped in the fire and his collar destroyed.

No other animals that are tracked by rangers, including coyotes and four bobcats, were believed to have died, he said.

The Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area stretches about 154,000 acres in northwest Los Angeles County.

About half of the park’s natural area burned, destroying vegetation and small animals that could not outrun the fast-moving fire and smoke, Riley said.

The animals that did survive had to flee to the fertile and habitable areas that remain. Park rangers are closely monitoring how they adapt and survive in what is one of the largest urban wildlife areas in the world.

Sperm production plummeted in some insects after heat waves

For years, insect populations have dropped worldwide without a clear explanation. A new paper suggests male infertility is at least one factor behind that decline, as warmer-than-usual temperatures take a disproportionate toll on males of some insect species.

After a lab-simulated heat wave, researchers from the University of East Anglia found that male flour beetles produced vastly less sperm. But they also found that the damage was not confined to the males. Sperm inside a female’s reproductive tract became less viable and the sons of the males that endured the hotter temperature became less fertile, too.

Matt Gage, an evolutionary ecologist who led the work published recently in Nature Communications, said he was surprised by the findings, and by how quickly male fertility plummeted.

It’s long been known that heat can affect sperm quality in mammals. “There’s a good reason the testes are outside the body,” noted Gage, adding that this keeps the sperm 0.4 to 1.2C cooler than body temperature.

But no one had previously looked to see whether coldblooded males were also affected, even though most of life on Earth is coldblooded, he said. And the flour beetles that Gage studied are used to warm environments, living in places that regularly reach 35C.

His team simulated a heat wave in their lab, raising temperatures by about 0.7 to 0.11C for five days – roughly equivalent to a temperature spike in England last summer, Gage said.

After the heat exposure, sperm production in the flour beetles dropped by half, the study showed. A second heat wave nearly sterilised them.

“We thought they might have hardened to temperature extremes,” Gage said. “We found the opposite.”

Females appeared unaffected by the heat themselves. But if they had already been inseminated, their fertility fell by 30 per cent after the heat exposure. This suggests that heat affects not just the manufacture of sperm, but also its later viability, Gage said.

The sons of the males who endured the heat wave produced 20 per cent fewer offspring than males that had not undergone that stress. Gage said he is not sure whether the sperm suffered DNA damage from the heat wave that could not be repaired, or if changes on top of the DNA – epigenetic changes – affected their sons’ fertility.

Drinking this milk could make your skin crawl

The act of breastfeeding is so fundamental to being a mammal that we named ourselves after it. (“Mammalis” translates to “of the breasts”.) But over time, scientists have discovered that other animals also produce nutrient-rich elixirs to feed their young, including flamingos, cockroaches and male emperor penguins.

The latest addition to the cast of organisms that lactate – or something like it – is a species of jumping spider.

Researchers in China have discovered that females of the Toxeus magnus spider secrete a milk-like fluid to feed their offspring. The study, published recently in the journal Science, also found the arachnid mothers continue to provide the fluid, which contains about four times as much protein as cow’s milk, well after their spawn had become young adults.

Although the spiders are not using mammary glands to produce the fluid, and hence are “lactating” in name only, the findings should prompt scientists to reconsider what they know about nursing and how it evolved, the researchers said.

“Finding such mammal-like behaviour in a spider, or in any invertebrate for that matter, was a surprise,” said Richard Corlett, a conservation biologist at the Chinese Academy of Sciences and an author of the study.

Jumping spiders are the single largest group of spiders in the world, with more than 5,000 species and a presence on nearly every continent. The tiny T magnus, also known as the black ant mimicking jumper, looks like an ant, walks like an ant and even waves its front legs in the air like a pair of antennas.

The study came about after the lead author, Zhanqi Chen, also of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, noticed that young T magnus seemed slow to leave the breeding nest, suggesting the mothers were providing some sort of extended child care.

Looking closer, they found that during the first week, the mother was depositing droplets of fluid from her underside onto the nest that the hatchlings would come to drink. After the first week, the offspring would drink the fluid directly from the mother’s body.

The researchers found that the mother continued to provide the fluid even after her young began leaving the nest to forage at about 20 days old. The suckling finally ceased at 40 days.

The extended nursing may be an evolutionary response to the creatures’ tiny size and vulnerability.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments