Science news in brief: From rolling water droplets to plastic and sea turtles

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A ghostly glow reveals how these plants fight back

Plants have no eyes, no ears, no mouth and no hands. They do not have a brain or a nervous system. Muscles? Forget them. They’re stuck where they started, soaking up the sun and sucking up nutrients from the soil. And yet, when something comes around to eat them, they sense it.

And they fight back.

How is this possible?

“You’ve got to think like a vegetable now,” says Simon Gilroy, a botanist who studies how plants sense and respond to their environments at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

“Plants are not green animals,” Gilroy says. “Plants are different, but sometimes they’re remarkably similar to how animals operate.”

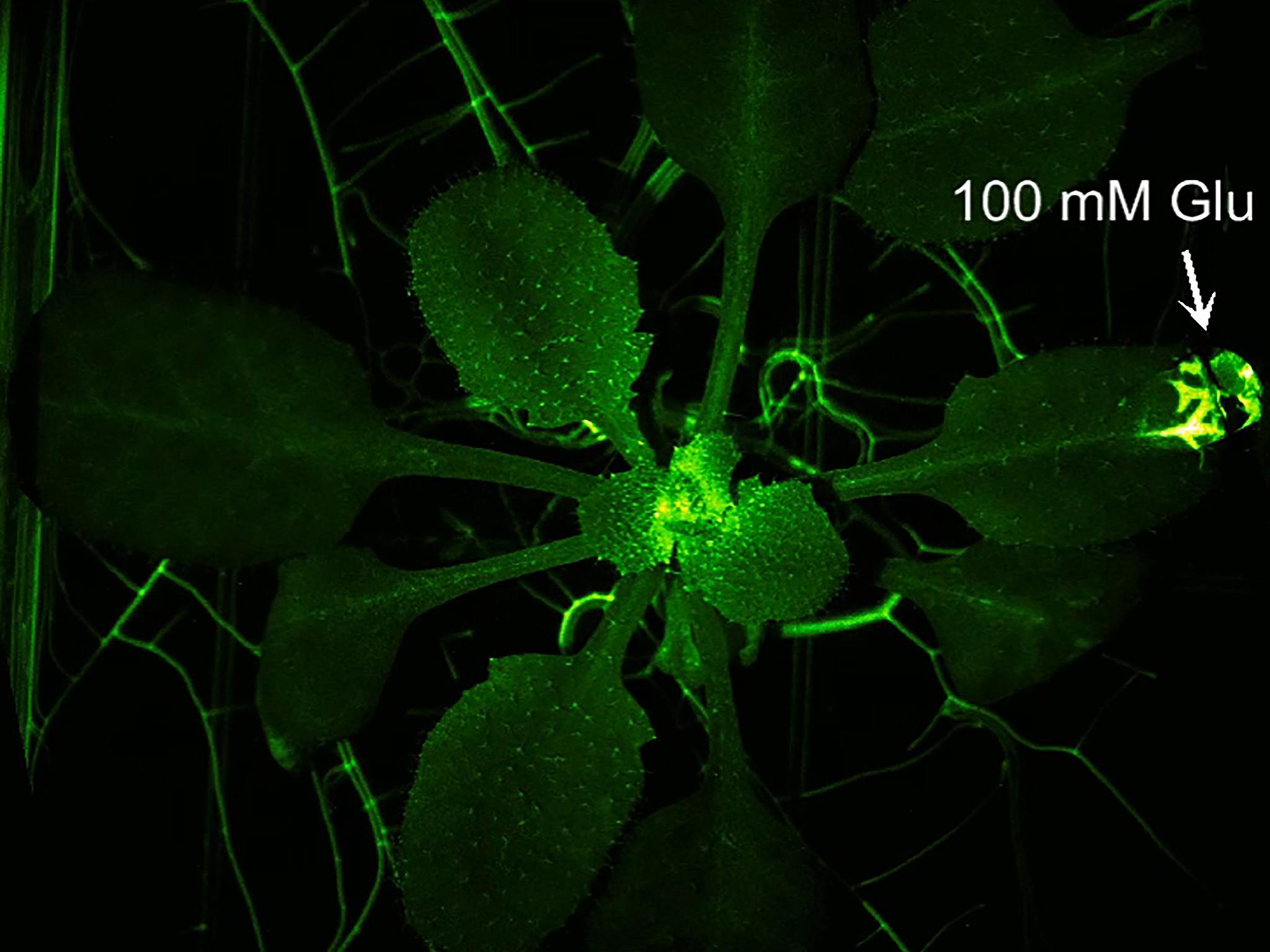

To reveal the secret workings of a plant’s threat communication system for a study published recently in Science, Masatsugu Toyota (now a professor at Saitama University in Japan) and other researchers in Gilroy’s lab sent in munching caterpillars. They also slashed leaves with scissors.

They applied glutamate, an important neurotransmitter that helps neurons communicate in animals.

In these and about a dozen other videos, they used a glowing, green protein to trace calcium and accompanying chemical and electrical messages in the plant. And they watched beneath a microscope as warnings transited through the leafy green appendages, revealing that plants aren’t as passive as they seem.

The messages start at the point of attack, where glutamate initiates a wave of calcium that propagates through the plant’s veins, or plumbing system. The deluge turns on stress hormones and genetic switches that open plant arsenals and prepare the plant to ward off attackers – with no thought or movement.

The real surprise was the speed. The plant reacted within a few seconds and transferred information from leaf to leaf in a couple of minutes – as long as they were connected through the vascular system. This is slower than your nervous system, but “for a plant biologist, that is booking it”, Gilroy says.

Water droplets don’t just hover on a hot pan. They roll

Drip water on a hot pan, and the droplets will skitter around the pan, speeding like tiny mad hovercraft on cushions of steam.

This is the Leidenfrost effect, which you’ve probably experienced while cooking. Johann Gottlob Leidenfrost, a German doctor and theologian, described the phenomenon in 1756 in a book about the properties of water.

But French scientists have now figured out something new about those skittering drops. When they are small enough – about a millimetre in diameter – the roiling of heat in the liquid will cause the droplet to tilt and rotate. That, in turn, propels the droplet to roll.

Scientists – and home cooks – never noticed this before, because no one had tried pinning a water droplet on a precisely flat surface. Plus, since water is clear, you usually can’t see which way the liquid is churning.

It was already known that the droplets, levitating on top of a layer of vapour, move easily, but the presumption was that they were sliding down a slope or pushed by air currents. The new research shows that they can move all by themselves.

“It’s embarrassingly simple,” David Quere, a scientist at the French National Centre for Scientific Research and Ecole Poytechnique, says of the discovery.

“The drop is running away,” he says. “It has a little motor inside, which is surprising. From this view, it’s amazingly different from usual drops, which, of course, stay where you place them.”

Quere and his colleagues described the research recently in the journal Nature Physics.

In the experiments, droplets of water were placed on a very flat, very hot, nonabsorbent surface, held in place by a needle.

Larger drops, those more than 1.5 millimetres in diameter, are more flattened in shape. Within the droplet, the liquid splits into two convective cells rotating in opposite directions. Think of two wheels spinning in opposite directions towards each other, one largely cancelling out the other.

As the water evaporates, the droplet shrinks and becomes nearly spherical, with room for just one convective cell. When the needle is lifted, the smaller droplet speeds off in the direction of the convective spin.

Quere calls it a Leidenfrost wheel.

Just a few pieces of plastic can kill sea turtles

All over the world, sea turtles are swallowing bits of plastic floating in the ocean, mistaking them for tasty jellyfish, or just unable to avoid the debris that surrounds them.

Now, a new study out of Australia is trying to catalogue the damage.

While some sea turtles have been found to have swallowed hundreds of bits of plastic, just 14 pieces significantly increases their risk of death, according to the study, published recently in Scientific Reports.

Young sea turtles are most vulnerable, the study found, because they drift with currents where the floating debris also accumulate, and because they are less choosy than adults about what they will eat.

Worldwide, more than half of all sea turtles from all seven species have eaten plastic debris, estimates Britta Denise Hardesty, the paper’s senior author and a principal research scientist with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Tasmania. “It doesn’t matter where you are, you will find plastic,” she says.

Six of the seven species of sea turtles are considered threatened, although many populations are recovering.

The study examined data from two sets of Australian sea turtles: necropsies of 246 animals and 706 records from a national strandings database. Both showed animals that died for reasons unrelated to eating plastic had less plastic in their guts than those that died of unknown causes or direct ingestion.

But the deaths are hard to pin down. “Just because a turtle has a plastic in it, you can’t say that it died from it, except in very extenuating circumstances,” Hardesty says.

Because of their anatomy, sea turtles cannot vomit up something once they have swallowed it, Hardesty says, meaning it either passes through their gut or gets stuck.

For a juvenile of typical size, half the animals would be expected to die if they ingested 17 plastic items, the study concluded. Sea turtles can live to be 80 or more years old, Hardesty says, with juveniles too young to reproduce ranging up to ages 20-30.

The study’s innovation was to try to determine this inflection point, where the load of plastic becomes lethal, says T Todd Jones, a supervisory research biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Hawaii.

An animal that swallows a lot of plastic might appear healthy, Jones says, but might be weakened by plastic in its gut, limiting food absorption.

As the ice melts, Nasa will be watching

On Saturday, climate scientists got a new eye in the sky, called ICESat-2, that will give researchers the sharpest look ever at melting glaciers, ice sheets and sea ice. All that melting ice contributes to sea-level rise, and ICESat will provide important information about how quickly it’s happening.

The new satellite has six lasers, firing 10,000 times a second. All those pulses of light will give this satellite astonishing precision. While the previous ICESat took measurements that were spaced apart roughly over the length of a football field at each end zone, the new one will measure between each yard line.

Nasa says it will be able to measure the change in elevation of the ice sheets in Antarctica and Greenland to about a sixth of an inch, less than the width of a pencil. “It’s going to enable science discoveries in the cryosphere and polar research for years to come,” says Tom Neumann, deputy project scientist for the new satellite.

Since this is ICESat-2, you know there was an earlier ICESat: it launched in 2003 and operated until 2009. Since then, Nasa has been taking measurements from airplanes flying over Greenland and Antarctica, a stopgap programme known as Operation IceBridge that has cost about $15m (£11m) a year.

Nasa isn’t simply replacing the old ICESat. Much of the cost of ICESat-2, which is about $1bn, went into creating a much more powerful instrument.

The satellite’s instrument, called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimeter System, or Atlas, will also measure the heights of forests to determine the amount of vegetation in a region, as well as monitor other attributes of land surfaces, water and clouds.

By precisely measuring the elevation of land ice, Atlas and ICESat-2 will help scientists develop a better sense of how much and how quickly that ice is melting in a warming world.

They’re blue, purple and red, and no one has ever seen them before

Out of the deep ocean comes a snub-nosed creature. It undulates up to a dead mackerel on a stick, thoughtfully lowered by scientists from the surface, and snaps its jaws.

This is a species of snailfish, and it’s never been seen before by human eyes. Snailfish look like fat, short eels and live all over the ocean, from shallow rock pools to the deepest trenches. This one, named the blue snailfish by its discoverers, lives at the bottom of the Atacama Trench, a great gash in the ocean floor nearly five miles deep off the coast of Chile and Peru.

The group from Newcastle University that observed it winched a lander, including a camera, the dead mackerel and other gear down into the depths on a cable this spring. Now the group has announced at this week’s Challenger Conference for Marine Science that they also discovered two additional species of snailfish, called for now the pink and purple snailfishes.

The snailfish of the deep ocean is a strange beast. For one thing, it’s quite mushy.

“The tissue is almost entirely gel,” says Thomas Linley, a research associate at Newcastle University who worked on the project. “They are really supported by the water around them.”

Their teeth and the tiny bones in the inner ear are the hardest parts of their bodies, and bringing snailfish up from the depths can feel like an exercise in futility. Without the pressure of the water and the chill of the deep ocean, they appear to melt on reaching the surface.

“They fall apart at like the molecular level,” Linley says. “It’s like a ghost thing that’s disappearing in front of your eyes.”

That makes it all the more exciting that the team managed to trap a purple snailfish. They have kept the body in a carefully controlled environment for further study.

So far, the same group has discovered the Mariana snailfish and the ethereal snailfish in the Mariana Trench in the western Pacific Ocean, and there is a specialised snailfish species in Kermadec Trench in the South Pacific as well.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments