Science news in brief: From East Island being wiped out to the world's largest organism

And a roundup of other stories from around the world

Pando, the biggest organism on Earth, is shrinking

On 106 acres in Fishlake National Forest in Utah, a 5 million kilogramme giant has been looming for thousands of years. But few people have ever heard of him.

This is “the Trembling Giant”, or Pando, from the Latin word for “I spread”. A single clone, and genetically male, he is a forest of one: a grove of some 47,000 quivering aspen trees – Populus tremuloides – connected by a single root system, and all with the same DNA.

But this majestic behemoth may be more of a Goliath, suggests a study published recently in PLOS ONE. Threatened by herds of hungry animals and human encroachment, Pando is fighting a losing battle.

The study, consisting of recent ground surveys and an analysis of 72 years of aerial photographs, revealed that this unrealised natural treasure and keystone species – with hundreds of dependents – is shrinking. And without more careful management of the forest, and the mule deer and cattle that forage within him, the Trembling Giant will continue to dwindle.

“It’s been thriving for thousands of years, and now it’s coming apart on our watch,” said Paul Rogers, an ecologist at Utah State University who led the study.

Pando is constantly reproducing, which is essential to its resilience. Lacking genetic diversity, it relies on having trees of different sizes and ages. That way, if one layer or generation dies off, there’s another waiting to replace it.

But Pando’s critical demographics are out of balance. When Mr Rogers and Darren McAvoy, a forestry colleague at Utah State, surveyed the forest, they found that older trees were dying, as expected, but that on the whole young ones weren’t replacing them.

Inadequate fencing, or the absence of it, seem to leave young patches of forest at the mercy of hungry mule deer, which are seeking refuge from hunters and increasing human activity. Foraging cattle, allowed into the park in the summer, are another factor in Pando’s shrinkage.

Aerial photos also revealed that Pando’s crown steadily thinned as human activity grew, especially in the last half century, with the addition of campgrounds, cabins and a telephone line, which drew animals that graze on forest leaves and shoots.

More fencing, culling of deer and experimentation with the forest’s natural ecology ultimately might save Pando, Rogers said.

East Island, remote Hawaiian sliver of sand, is largely wiped out by a hurricane

Before Hurricane Walaka swept through the central Pacific this month, East Island was captured in images as an 11 acre sliver of sand that stood out starkly from the turquoise ocean.

After the storm, government officials confirmed that the island, in the northwestern part of the Hawaiian archipelago, had been largely submerged by water, said Athline Clark of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). East Island is the second island to disappear in recent months from French Frigate Shoals, a crescent-shaped reef including many islets, she said.

Chip Fletcher, a climate scientist with the University of Hawaii who has been studying East Island’s natural history, said it comprises loose sand and gravel rather than solid rock.

Athline Clark, the NOAA superintendent for the Papahanaumokuakea Marine National Monument, which includes the French Frigate Shoals, said no one immediately realised the island had largely disappeared because it is so remote. It is 750 miles northwest of Oahu, the island that is home to Honolulu.

The low-lying island, with its sandy composition, wasn’t much of a match for the storm in early October, which started off as a category five hurricane and created large storm swells, Ms Clark said.

Although experts cannot directly trace the shrinking of East Island to the effects of climate change, Ms Clark said, it contributes to the strength and frequency of hurricanes like the one that overtook the island. Scientists say hurricanes will be stronger because warmer water provides more energy to feed them.

Charles Littnan, a conservation biologist with NOAA Pacific Islands Fisheries Science Centre, said about 96 per cent of Hawaiian green sea turtles, a threatened species, travel to the French Frigate Shoals to nest. About half used East Island, he said.

The shoals are also home to more than 200 endangered Hawaiian monk seals. Only 1,400 of the species remain in the area.

It is possible that East Island will resurface and the turtles and seals will return to their seasonal homes. In images of the island after the storm, Mr Littnan said he could already see that some monk seals had returned and hauled themselves onto the 150ft long patch of sand that remained.

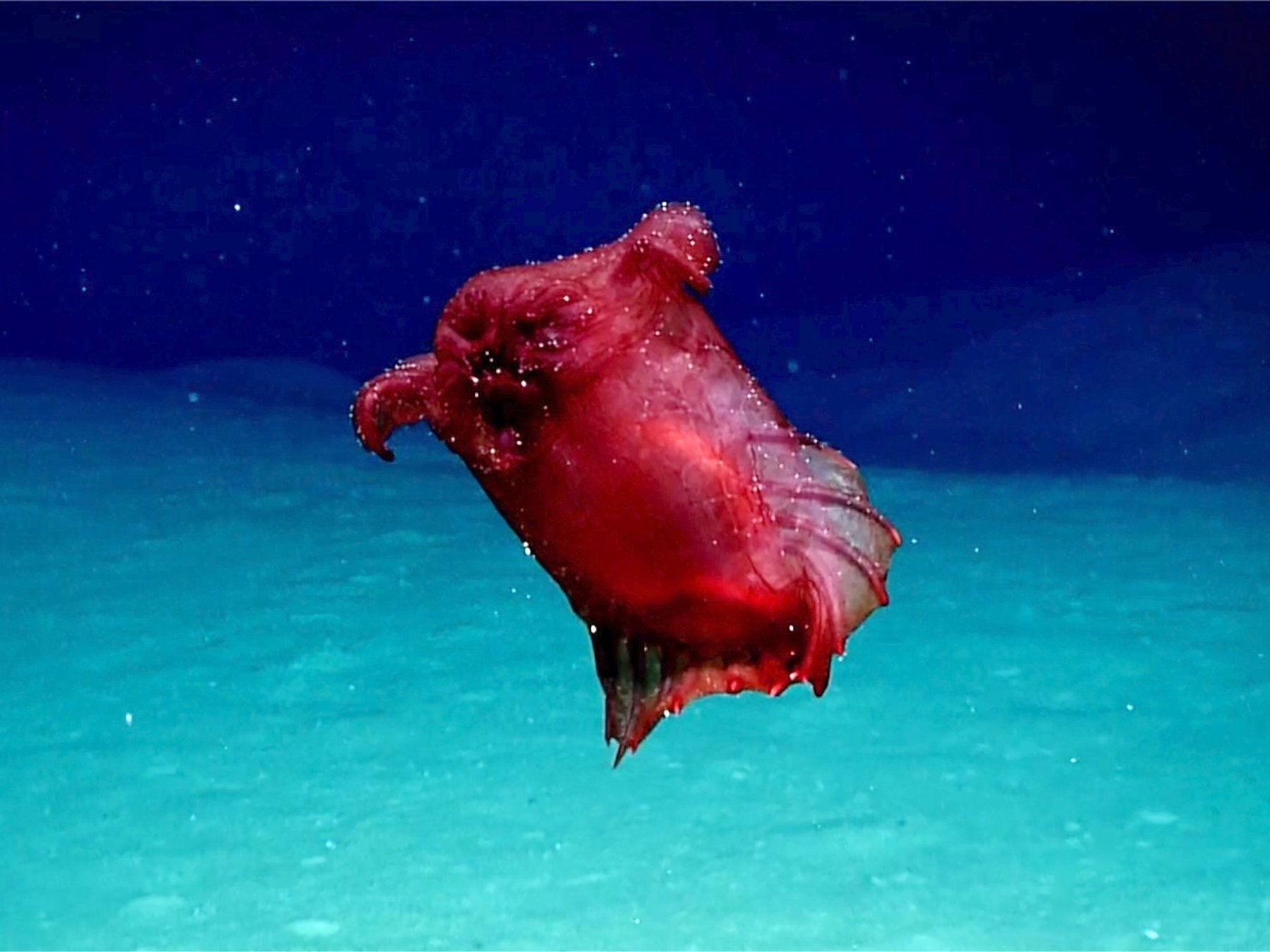

‘Headless chicken monster’ spotted in deep sea

What lives a mile under the sea, has tentacles and fins and looks like a decapitated chicken ready for roasting? The headless chicken monster, of course.

Yes, that is actually the name of a rare creature caught on film recently by researchers working in the Antarctic Ocean, about 4,000km (2,500 miles) off the southwest corner of Australia.

The “monster”, actually a sea cucumber that helps to filter organic matter on the ocean floor, has been caught on film only once before – last year in the Gulf of Mexico.

Floored by its unusual physique, scientists call it the headless chicken monster. (It is also known as the swimming sea cucumber, the Spanish dancer and by its scientific name – Enypniastes eximia.)

“It looks a bit like a chicken just before you put it in the oven,” said Dirk Welsford, the programme leader for the Australian Antarctic Division, who was among the researchers to spot the animal off the coast of Antarctica.

As part of a project to explore the effect of fishing on sensitive marine ecosystems, Mr Welsford and his team attached specially designed cameras to fishing lines dropped to depths of 3km.

This particular project, he said, was designed to explore the effects of commercial fishing on two species: the Antarctic toothfish and the Patagonian toothfish, better known to US consumers as Chilean sea bass.

“We had no idea what it was,” Mr Welsford said upon seeing footage of the creature for the first time.

Unlike most sea cucumbers, the headless chicken monster has fins, which allow it to swim upward to escape predators.

“From a research point of view it’s very interesting because no one has seen that species that far south before,” Mr Welsford said, adding that discovering the animal near Antarctica could help scientists understand the species’ distribution, and how it might be affected by climate change.

While sightings of the sea cucumber go back to the late 1800s, scientists have “absolutely no idea” how many there are in the world’s oceans, he said. It’s “an amazing reflection of how little we know about the deep ocean”.

Lavender’s soothing scent could be more than just folk medicine

We have been using this violet-capped herb since at least medieval times. Lavender has purported healing powers for reducing stress and anxiety. But are these effects more than just folk medicine?

Yes, said Hideki Kashiwadani, a physiologist and neuroscientist at Kagoshima University in Japan, at least in mice.

“Many people take the effects of ‘odour’ with a grain of salt,” he said in an email. “But among the stories, some are true based on science.”

In a study published recently in the journal Frontiers in Behavioural Neuroscience, he and his colleagues found that sniffing linalool, an alcohol component of lavender odour, was kind of like popping a Valium. It worked on the same parts of a mouse’s brain, but without all the dizzying side effects. And it did not target parts of the brain directly from the bloodstream, as was thought. Relief from anxiety could be triggered just by inhaling through a healthy nose.

Their findings add to a growing body of research demonstrating anxiety reducing qualities of lavender odours, and suggest a new mechanism for how they work in the body. Mr Kashiwadani believes this new insight is a key step in developing lavender-derived compounds like linalool for clinical use in humans.

In this study, researchers exposed mice to linalool vapor, wafting from filter paper inside a specially made chamber to see if the odour triggered relaxation. Mice on linalool were more open to exploring, indicating they were less anxious than normal mice. And they did not behave like they were drunk, as mice on benzodiazepines, a drug used to treat anxiety, or injected with linalool did.

But the linalool did not work when they blocked the mice’s ability to smell, or when they gave the mice a drug that blocks certain receptors in the brain. This suggested that to work, linalool tickled odour-sensitive neurons in the nose that send signals to just the right spots in the brain – the same ones triggered by Valium.

Although he has not tested it in humans, Kashiwadani suspects that linalool may also work on the brains of humans and other mammals, which have similar emotional circuitry.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments