Science news in brief: From hurricane lizards to dancing black holes

And other stories from around the world

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Holding on for dear life, and for Darwin’s point of view

Two years ago, Colin Donihue, a biologist, released a sober scientific paper along with a series of endlessly GIF-able videos. They showed Caribbean anole lizards flailing in the wind from a leaf blower, holding on to a stick for dear life, not unlike the kitten in the classic “Hang In There, Baby” poster.

No anoles were harmed. But by proving how a lizard would try to grit its way through hurricane-force winds with sheer grip strength, those whimsical experiments led Donihue, now at Washington University in St Louis, and a team of other researchers to a profound suggestion: extreme weather events may bend the evolutionary course of hundreds of species. A paper published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences offers deeper evidence of their earlier finding.

Across central and South America and the Caribbean islands, scientists found that lizards with larger toe pads seem to be more common in areas that have been hit by storm after storm in the past 70 years. That suggests that severe but fleeting cataclysms don’t just leave lasting scars on people and places. They also reshape entire species.

“We racked our brains for alternate explanations for this pattern,” Donihue says. Could it be temperature? Precipitation? Taller or shorter trees in different locations? “Nothing we tried explains that variation as strongly as hurricane history.”

Not long after Donihue had been lassoing Anolis scriptus lizards with a loop of string at the end of a fishing rod on a pair of small islands in Turks and Caicos for what was supposed to be just a local conservation project, the same islands were blasted by a one-two punch of extreme weather.

First came Hurricane Irma, a screaming maelstrom of 160mph winds. Two weeks later came Hurricane Maria. When Donihue returned, trees were down and lizards were scarce. On average, he found the surviving anoles seemed to have much bigger, grippier toe pads than the population had averaged before, as if those with less sticky feet had been carried away by the storms.

That initial finding came out with the leaf blower videos. But the team kept digging. Eighteen months after the storm, Donihue went back to Turks and Caicos a third time to find a new generation of lizards scampering across new plant growth. Those carefree children of the survivors had kept their parents’ generation’s bigger toe pads.

These birds eat fire to live another day

Rufous treepies, birds in the crow family native to south and southeast Asia, usually eat insects, seeds or fruits. But some of them have learned to eat fire.

Well, not exactly, but close. At a small temple in the Indian state of Gujarat, the caretakers regularly set out small votive candles made with clarified butter. The birds flit down to steal the candles, extinguish the butter-soaked wicks with a quick shake of their heads and then gulp them down.

This willingness to experiment with new foods and ways of foraging is an indicator of behavioural flexibility, and some scientists think it is evidence that certain species of birds might be less vulnerable to extinction.

“The idea is that if a species has individuals that are capable of these novel behaviours, they’ll respond with changes in their behaviour more easily than individuals from species that do not tend to produce novel behaviours like that,” says Louis Lefebvre, a professor at McGill University in Montreal and an author on the study. “The idea is pretty simple. The problem was to be able to test it in a convincing way.”

A team of researchers, led by Simon Ducatez of Spain’s Centre for Research on Ecology and Forestry Applications, combed through 204 ornithological journals for mentions of novel behaviours and feeding innovations, comparing the number of sightings in each species with their risk of extinction. Their results have been published in Nature Ecology & Evolution.

Lefebvre says the approach provided backup to earlier cognition experiments he had led with birds caught in the wild, such as testing their ability to figure out how to open boxes full of food.

“People that watch birds – ornithologists, bird watchers – tend to report whenever they see unusual feeding behaviours,” he says. “That’s a gold mine to get a database on all possible species all over the world.”

Some of the reported innovations were subtle, with seedeaters like northern cardinals feasting on nectar from nonnative garden plants. Others were more remarkable: cormorants in New Zealand using the strong currents left in the wake of ships to go fishing, green herons deploying breadcrumbs as bait to catch fish, great blue herons hunting squirrels on golf courses and – famously – gulls stealing bags of chips.

The team’s own observations complemented the data from ornithology journals. In Barbados, for example – where Lefebvre maintains a field station – tourists often see native bullfinches eating remains of food on tables, including sugar from bowls. But the birds also steal packets of sugar, which they take away, peck open and devour. Native Carib grackles on the island also take dry pet food and dip it in rain puddles to soften and eat it.

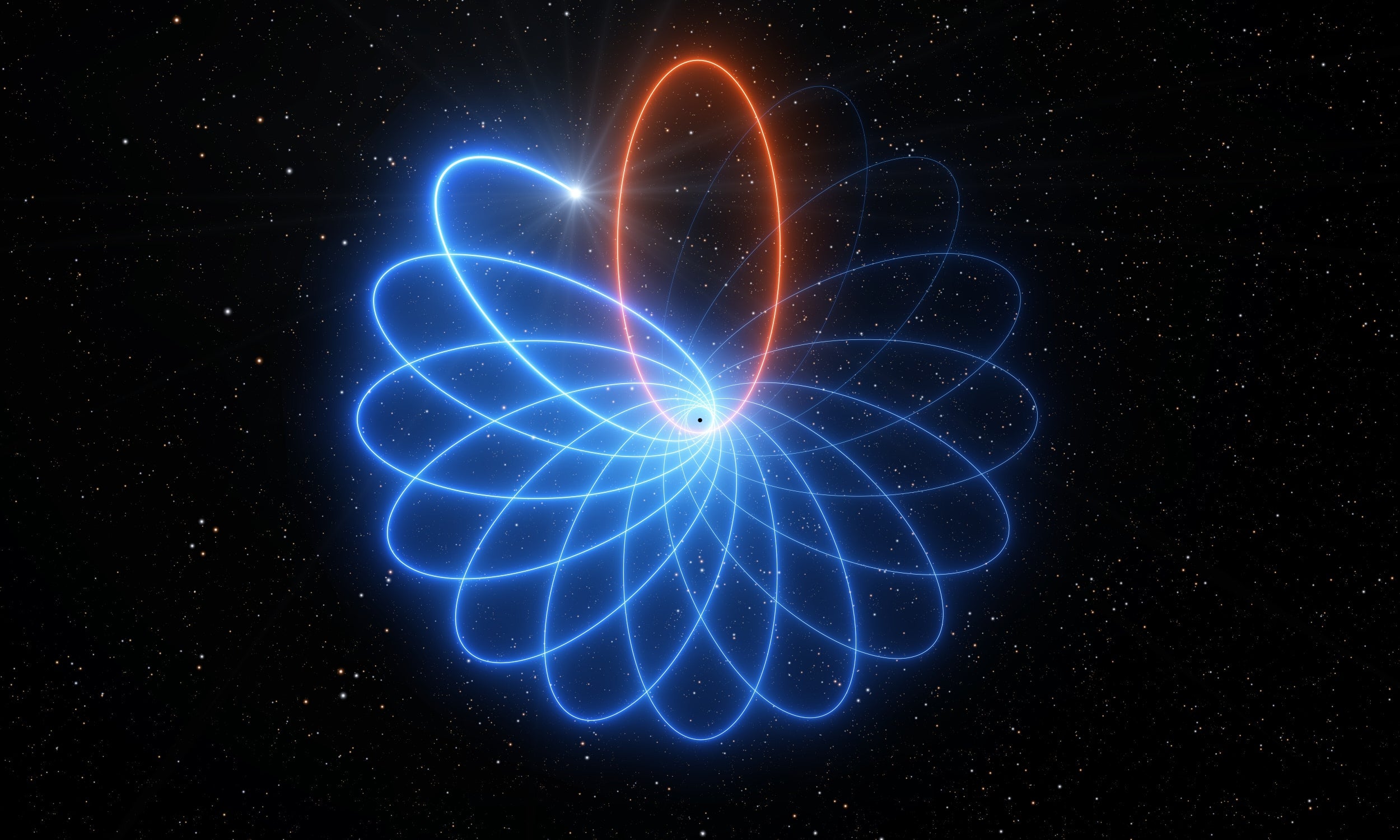

Dancing with a black hole

For decades, astronomers have had their earthly eyes on the adventures of a star known as S2 that tickles the edges of oblivion.

Every 16 years, the star’s orbit takes it within a cosmic whisker’s breadth – 11 billion miles – of the lip of what is believed to be the supermassive black hole Sagittarius A*, the pothole in eternity at the centre of the Milky Way galaxy. That black hole has consumed mass equivalent to four million suns. During its fraught passages, the S2 star experiences the full strangeness of the universe, according to Einstein.

One result of this strangeness, now determined after 27 years of high-precision observations with the European Southern Observatory’s Very Large Telescope in Chile is that the star’s egg-shaped orbit does not stay fixed in space. Reinhard Genzel, an astronomer at the Max Planck Institute for Extraterrestrial Physics, and his colleagues describe the star’s unusual journey around the black hole in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics.

The orbit itself rotates around the black hole. The star’s closest point to the black hole, known as perihelion, advances around in a circle by about a fifth of a degree – 12 arc minutes. At this rate the orbit will do a complete loop in only 28,800 years, a mere cosmic eye blink.

It’s another score for Albert Einstein and his general theory of relativity, which ascribes the phenomenon we call gravity to a warping of the geometry of space and time. Black holes, objects so dense that space has sagged around them, swallowing even light, are one consequence of his theory. Another is that orbits around particularly dense objects won’t stay still. They will do a pirouette around the object of their attraction.

New York and Boston pigeons don’t mix

Almost one in five Americans lives in the megacity that is the northeast, a sprawling cluster of paved surfaces, bitter sports rivalries and clashing opinions about which city’s drivers are rudest.

Each city on the road up Interstate 95 from Washington, DC, to Boston prides itself on its uniqueness. But it turns out parts of the animal world have their own senses of geography.

At the genomic level, a new study finds, most of the Eastern Seaboard’s pigeons are all mixed up. That means those birds shuffling through Central Park, clucking on the National Mall or hanging out in Baltimore’s Inner Harbour are all one interconnected population, denizens of an unbroken avian super metropolis.

Except New England pigeons, that is, which seem to keep to themselves.

After Elizabeth Carlen, a biologist at Fordham University, caught pigeons with a net gun and took their blood samples during a series of road trips across the region, she discovered that birds all the way from Virginia to southern Connecticut show genetic signs of interbreeding. And in a paper published in Evolutionary Applications, she and a co-author also report that another separate, distinct pigeon supercity begins in Providence, Rhode Island and continues to Boston.

“That was really weird to think about,” Carlen says. The suburbs of Connecticut don’t just mark the boundary between Yankees and Red Sox fans, or tomato-based and cream chowders: they also seem to block pigeons.

Discovering two distinct pigeon megalopolises was itself a surprise to Carlen.

“My original hypothesis was that each city was going to be a separate population,” she says. Previous studies have shown that pigeons are homebodies, staying within hundreds of feet of where they were born.

But it’s possible that all it takes is one intrepid pigeon finding an out-of-town mate every generation to explain how cities like Baltimore, Washington, Philadelphia and New York can have so many genetic similarities, she says.

Less than 200 miles separate New York and Boston, but something between the rival towns forms an uncrossable moat for city-slicker pigeons. A look at satellite maps of artificial light at night highlights the gap between the two metropolitan areas – a break in what is otherwise continuous urban sprawl. Although the birds can fly, all that rural green space might dissuade them from attempting a crossing.

The ghost dogs of the Amazon get a bit less mysterious

It is one of the Amazon rainforest’s most elusive and enigmatic mammals. Experts call the species “shy” or even “a ghost”. It’s a dog.

Or at least a type of dog. The short-eared dog is the only member of the canine genus Atelocynus, and the only such species unique to the Amazon rainforest. In a study published in Royal Society Open Science, 50 researchers chipped away at the creature’s mysteries by putting together a large location data set gleaned mostly from camera trap cameos. By mapping the species’ range and determining its preferred habitat, the scientists, many of whom have never encountered the animal in person, hope to help protect it.

Daniel Rocha, a graduate student at the University of California, Davis, and the study’s lead author, became interested in the short-eared dog in 2015, when he began working in the southern part of the Amazon. He and his colleagues set up camera traps to study the local mammal community. As they looked through the footage, “these dogs would appear”, he says. With pricked ears and furrowed brows, they almost look surprised to be caught on camera.

It surprised him, too. Even locals who spend a lot of time in the Amazon don’t often see short-eared dogs, which were assumed to be quite rare. They also evade career researchers focused on this region: Rocha, who spent years leading this study, says, “I’ve never seen the dog in the jungle, ever”.

When Rocha started contacting his peers about the short-eared dog, he found that nearly “every researcher in the Amazon had a little bit of data” – a camera trap snapshot or two, he says.

By combining location data from the traps with the few in-person sightings, as well as information from specimens found in natural history collections, Rocha and his co-authors were able to estimate the short-eared dog’s range. They found a wider distribution than previous studies had – the dog has been seen in five countries, and seems to inhabit an area bordered on the west by the Andes, the north by the Amazon River and the south and east by the rainforest’s edge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments