Science news in brief: From Saturn's moons to ancient structures of mammoth bones

And other stories from around the world

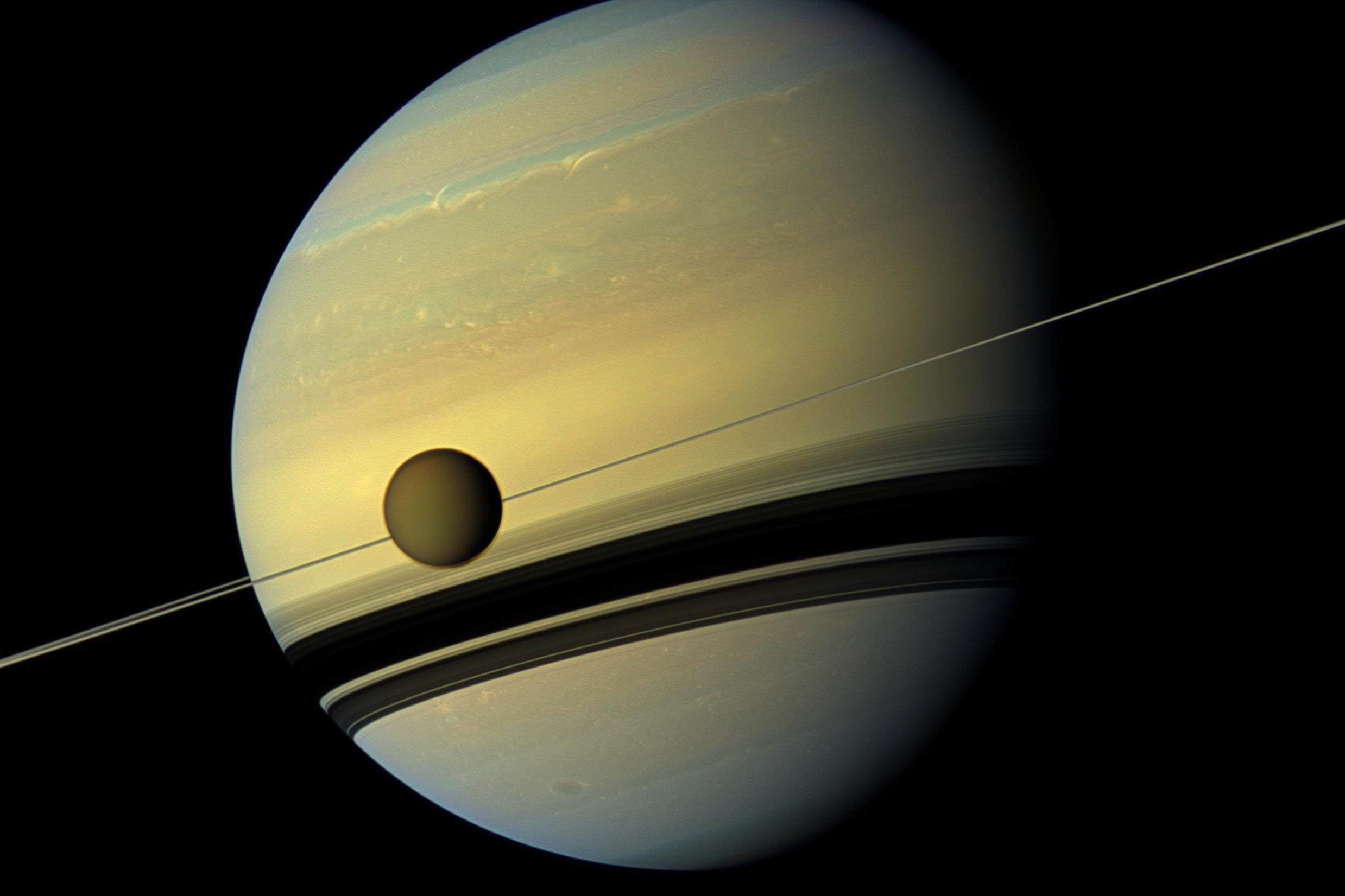

Why didn’t Saturn eat Titan, its biggest moon?

In classical mythology, the titan Cronus, who was reinterpreted by the Romans as Saturn, devoured his newborn children to prevent a prophesied coup. (He did not succeed, and Zeus became the king of the gods.)

In planetary science, a similar scenario emerges when scientists recreate the evolution of large planets like Saturn, which has a satellite system dominated by one massive moon, Titan. Typically those simulated planets either eat their orbital retinue, or multiple sizeable moons survive into adulthood, like the four Galilean moons of Jupiter.

How, then, did Saturn end up with massive Titan and a multitude of tinier moons? Using a set of simulations detailed in the journal Astronomy and Astrophysics, a team of planetary scientists identified an explanation for how a moon like Titan could have avoided straying too close to its murderous parent.

“Titan is one of the largest moons in our solar system,” says Yuri Fujii of Nagoya University and lead author of the new study. “I would like to reveal its origin.”

She and a colleague attempted a detailed simulation of moon formation for a planet at Saturn’s distance from the sun. Instead of considering a large world surrounded by a simplified, gassy disk, she modelled an environment with more intricate, fine-scaled temperatures and densities. Then, she tweaked the amount of turbulence in the gas itself. They then simulated more than 100,000 years of moon evolution, adding in the gravitational jostling caused by migrating satellites and accounting for the disk’s dissipation over time.

She found that a swath of space emerges within the disk that acts like a safety zone. That zone is a dusty expanse with a steep temperature change between its warmer inner edge, closer to the planet, and the colder outer edge, nearer to the void. Warm gas inside that band, which fluctuates between 20 and 100 planetary radii from the infant planet, prevents farther-flung moons such as Titan from moving inward and becoming snacks for the young planet. But moons that already live on the interior of the safety zone are out of luck.

The simulation, Fujii says, reproduces a satellite system with a single, large moon around a Saturn-like planet – although that outcome largely depends on how long it takes the gas in the disk to vanish, and how far from the planet the large moons initially form.

This Mom is still pregnant. But she’s already having another baby

Kangaroos and wallabies don’t reproduce the way most of their fellow mammals do – they keep their pregnancies short and to the point, with their young crawling out of the womb and up to their mother’s pouch after just a month’s gestation. Once there, the tiny joeys spend about nine months nursing and growing before they’re ready to climb out of the pouch into the world.

Almost all kangaroos and wallabies have two separate uteruses, and they usually contrive to have extra, undeveloped embryos waiting in the wings – or rather, in whichever uterus was unused in their most recent pregnancy.

But researchers report in a study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that the swamp wallaby has an even more peculiar way of doing things. It gets pregnant again before the first pregnancy is even over, suggesting that female swamp wallabies may be pregnant continuously for their entire reproductive lives.

Swamp wallabies are delicate, skittish creatures, says Brandon Menzies, one of the paper’s authors. While researchers had suspected for decades that they were doing something unusual, answers were not forthcoming until he and his co-authors, Thomas Hildebrandt of the Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research in Germany and Marilyn Renfree of the University of Melbourne, managed to use ultrasound scanners on pregnant females.

The researchers monitored 10 pregnancies in the University of Melbourne’s captive wallaby colony. They gently sedated some creatures and scanned their pouches and uteruses, while they looked into others’ pouches regularly for new young, and they swabbed the females for sperm to pinpoint when mating had occurred.

Based on traces of sperm found in the days before the birth of the first joey, the researchers found that the wallabies’ estrus, or mating period, began before the pregnancy was over. What’s more, in the case of two females who lost their young in the final day or so of gestation, an ultrasound 10 days later showed they had already grown a 12-day embryo in the other uterus. That implied that fertilisation had occurred two days before the losses.

“Potentially, these animals are always pregnant,” says Menzies, with not even a day or two between pregnancies.

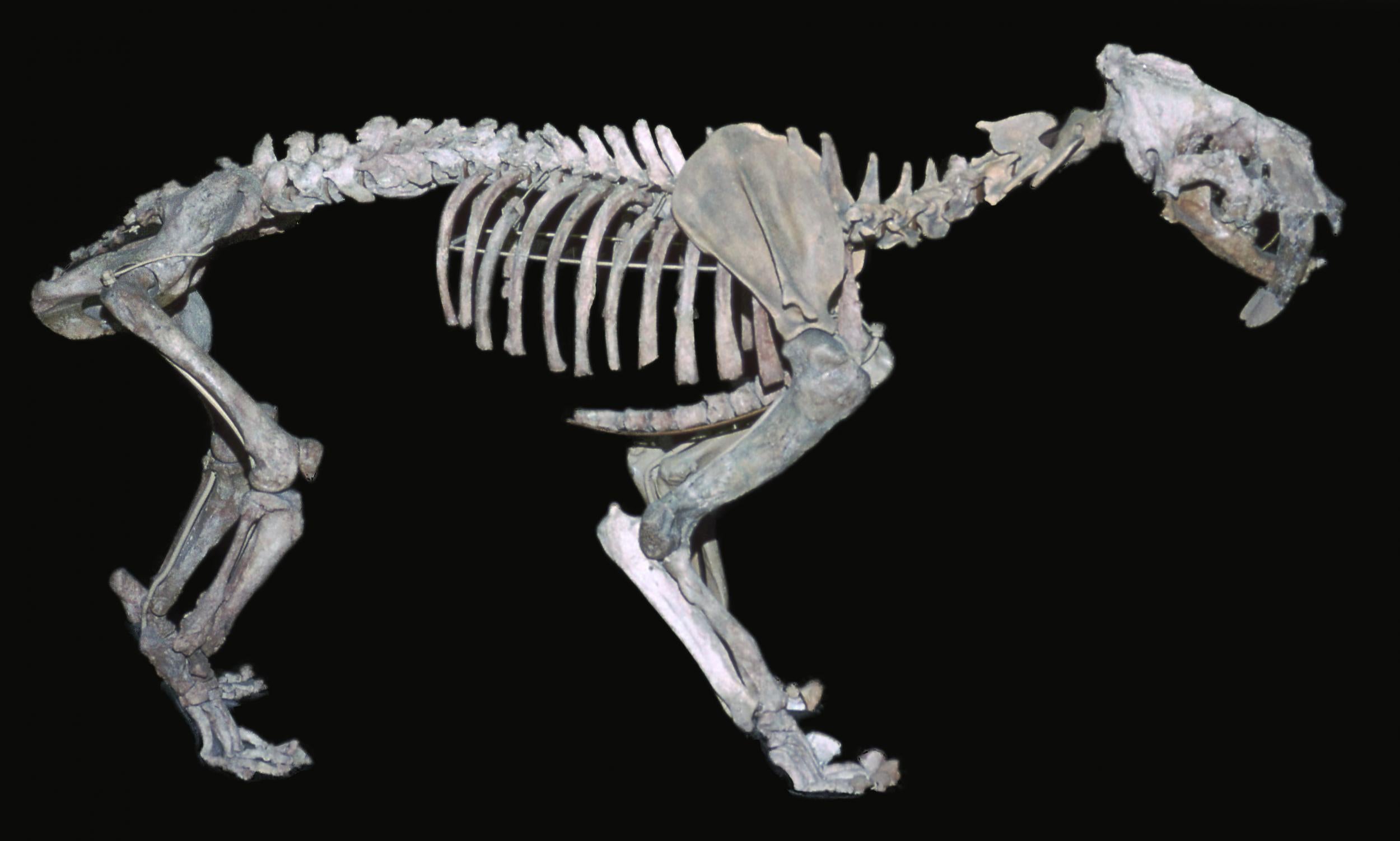

They knew saber-toothed tigers were big. Then they found this skull

When the curator mentioned a huge saber-toothed tiger skull stored behind the scenes of the National Museum of Natural History in Montevideo, Uruguay, Aldo Manzuetti had to see for himself.

The skull belonged to Smilodon populator. Extinct for about 10,000 years, the heavily muscled species once Hulk-smashed its way through South American fauna in the Pleistocene. To picture a normal individual, start with an African lion. Then double its size and add giant fangs.

But this one wasn’t normal. The skull was 16in long, making previous large specimens from the species look small. “I thought I was doing something wrong,” says Manzuetti, a doctoral student in palaeontology at Uruguay’s University of the Republic. He was using the head to infer the likely size of the animal’s body. “I checked the results a lot of times, and only after doing that I realised I hadn’t made any mistakes.”

His analysis showed the skull sat atop a beast that likely tipped the scales at around 960 pounds. The specimen’s existence, he and colleagues reported earlier this month in the journal Alcheringa, suggests that the largest saber-toothed tigers might have been able to take down giant plant-eaters, heavy as pickup trucks, that researchers had thought were untouchable.

Ricardo Praderi, an amateur collector, first dug up the prehistoric predator’s skull in September 1989 in southern Uruguay. The site had otherwise yielded only the fossils of herbivores. He then donated it to the archives of the national museum, Manzuetti says.

Scientists knew South America was haunted by the ghosts of vanished Pleistocene carnivores. But the top tier of possible prey – armoured armadillos comparable to Volkswagens, lumbering mastodons, the 12ft-tall ground sloth Megatherium – would have challenged even the fiercest hunter.

“We’ve always wondered: Who could take down a giant ground sloth?” says Kevin Seymour, a palaeontologist at Toronto’s Royal Ontario Museum who reviewed the research.

The new skull suggests an answer. “If Smilodon is getting this big, there’s a potential for it to be taking down these giant adult herbivores,” Seymour says.

These ants have a revolutionary escape strategy

Ants are bristling with defence weaponry. Different species might sting their enemies, bite them with powerful jaws or shoot them with jets of formic acid. Some even explode.

But Myrmecina graminicola – an ant about the size of a sesame seed – doesn’t want to get into all that. According to research published last week in Scientific Reports, if one of these ants encounters danger while it’s on a slope, it makes a practical choice: it tucks itself into a little ball and rolls away.

It is the only ant known to move in this way, and one of few rollers in the animal kingdom overall, says Donato Grasso, the paper’s lead author and an ant ethologist at the University of Parma in Italy.

Grasso and his colleagues first spotted this unique behaviour while scanning the forest floor during a trip to one of their field sites in Fornoli, Italy. (Many entomology discoveries are made this way: “When you are a biologist interested in insects, it is impossible not to look at the ground,” Grasso says.)

The team found a few colonies of M graminicola, which are so small and elusive they often go unnoticed. When the insects were menaced by spiders and other ants, “they curled their bodies and disappeared” into the leaf litter, Grasso says. “They rolled away.”

In the lab, the researchers use slow motion video to tease out the ants’ choreography. Roughly: A ready-to-roll ant tucks in its head and pulls its abdomen forward to form a ball. It then lifts its legs up and tips itself forward to rest on its mandibles and antennae, which balance it like arms, Grasso says. A final push with the hind legs, and it’s off.

On smoother surfaces like stones and leaves, the ants travelled at about 15in per second – about 80 times faster than their average walking speed. They could move themselves about 6in, or about 50 body lengths.

Such a distance is “pretty impressive”, and shows that the ants’ rolling form must be very efficient, says Nicholas Gravish, an engineer who studies ant locomotion at the University of California and was not involved in the new research.

This mysterious ancient structure was made of mammoth bones

Ice Age hunter-gatherers, foraging the bone-chilling, unforgiving steppes of what today is Russia, somehow completed a remarkable construction project: a 40ft-wide, circular structure made from the skulls, skeletons and tusks of more than 60 woolly mammoths. The reason remains a mystery to archaeologists.

“The sheer number of bones that our Paleolithic ancestors had sourced from somewhere and brought to this particular location to build this monument is really quite staggering,” says Alexander Pryor, an archaeologist at the University of Exeter. “It does boggle my mind.”

Alexander Dudin, a researcher from the Kostenki Museum-Preserve, and a team of scientists began excavating the 25,000-year-old mammoth-bone circle in 2014 at a site called Kostenki 11, which is 300 miles south of Moscow. It is the third structure uncovered at the site. The discovery was published Monday in the journal Antiquity.

Archaeologists have unearthed about 70 mammoth bone structures across Eastern Europe. But this one is the oldest on the Russian plain thought to be made by modern humans. Most of the previously identified structures were small, leading researchers to conclude they were most likely used as winter dwellings on a nearly treeless landscape.

Pryor arrived at Kostenki 11 in 2015. The ring, which also included ribs, jaws and leg bones, had probably been piled 20in high before collapsing thousands of years ago, he says. The team collected sediment samples from inside the bone circle and from three large pits located outside.

Through further processing, they identified more than 400 charcoal pieces, evidence of wood-burning. The charcoal came from conifers such as spruce, larch and pine, suggesting that trees still grew in the harsh, frozen environment. They also radiocarbon-dated the charcoal, which further supported that the site was about 25,000 years old.

They also found burnt mammoth bones, which indicated that the Paleolithic people were probably starting fires with wood and then using the beasts’ greasy bones to feed the flames. Bone-fueled fires burn brighter than wood fires, but spread less warmth.

The team acknowledge that they did not fully solve the mystery of how the mammoth-bone circle was used. They still do not know whether the hunter-gatherers killed or scavenged the beasts, how long the location was used or if it held any ritualistic importance.

© The New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments