A new (old) cure for MRSA? Revolting recipe from the Dark Ages may be key to defeat infection

Scientists have been 'dumbfounded' at the infection-killing ability of the ancient 10th Century cure, after a series of tests in Britain and the US during the past year

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

A stomach-churning potion from the Dark Ages could be the death of the modern day Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, according to researchers who claim that the ancient treatment outperforms conventional antibiotics.

Scientists have been “dumbfounded” at the killing ability of the potion - an ancient cure for eye infections dating back to the 10th Century - after a series of tests in Britain and the US during the past year.

That the Anglo-Saxon recipe, which includes wine, garlic, and bile from a cow’s stomach, could hold the key to defeating MRSA came about after a chance discussion between experts at the University of Nottingham last year.

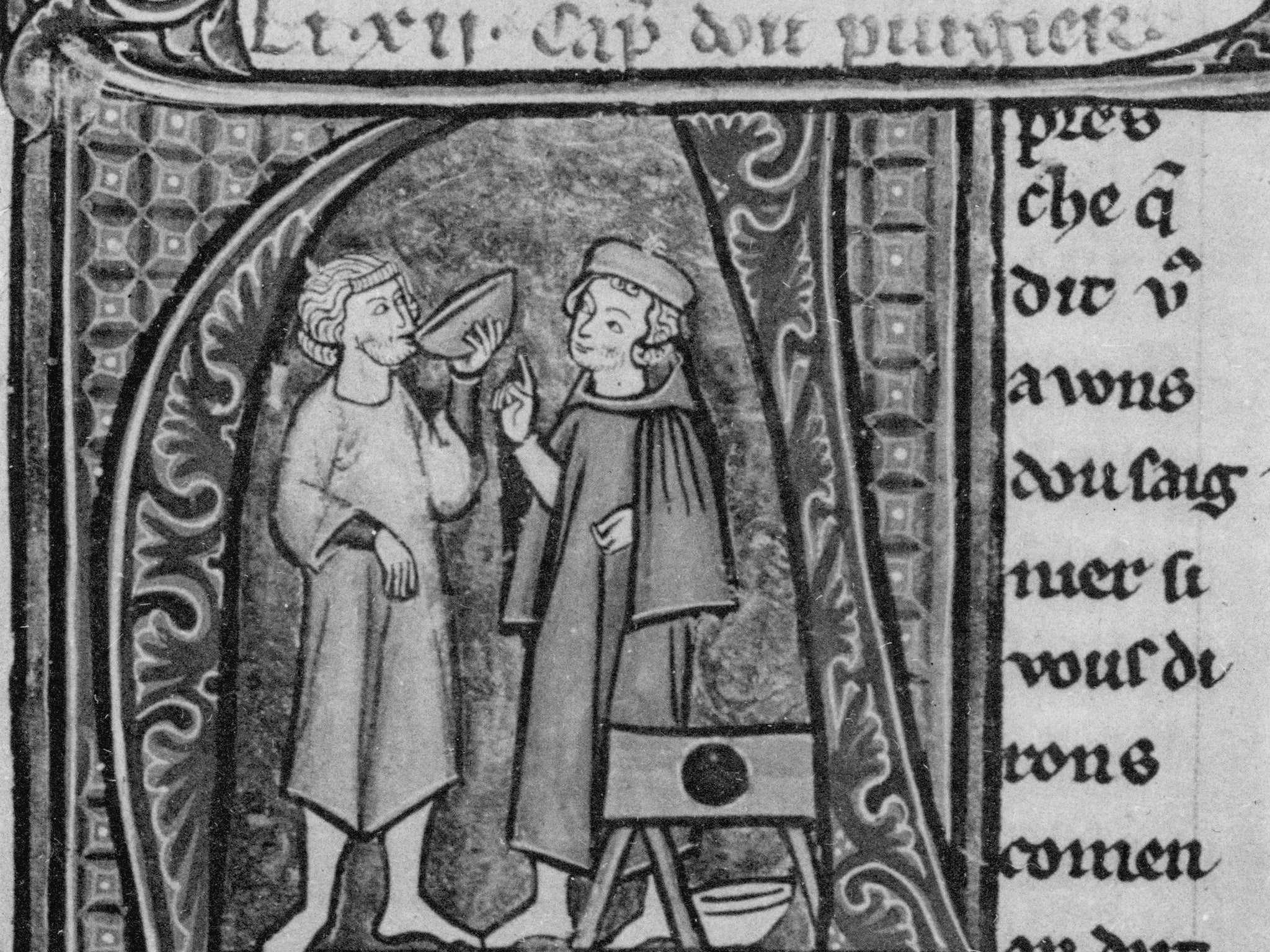

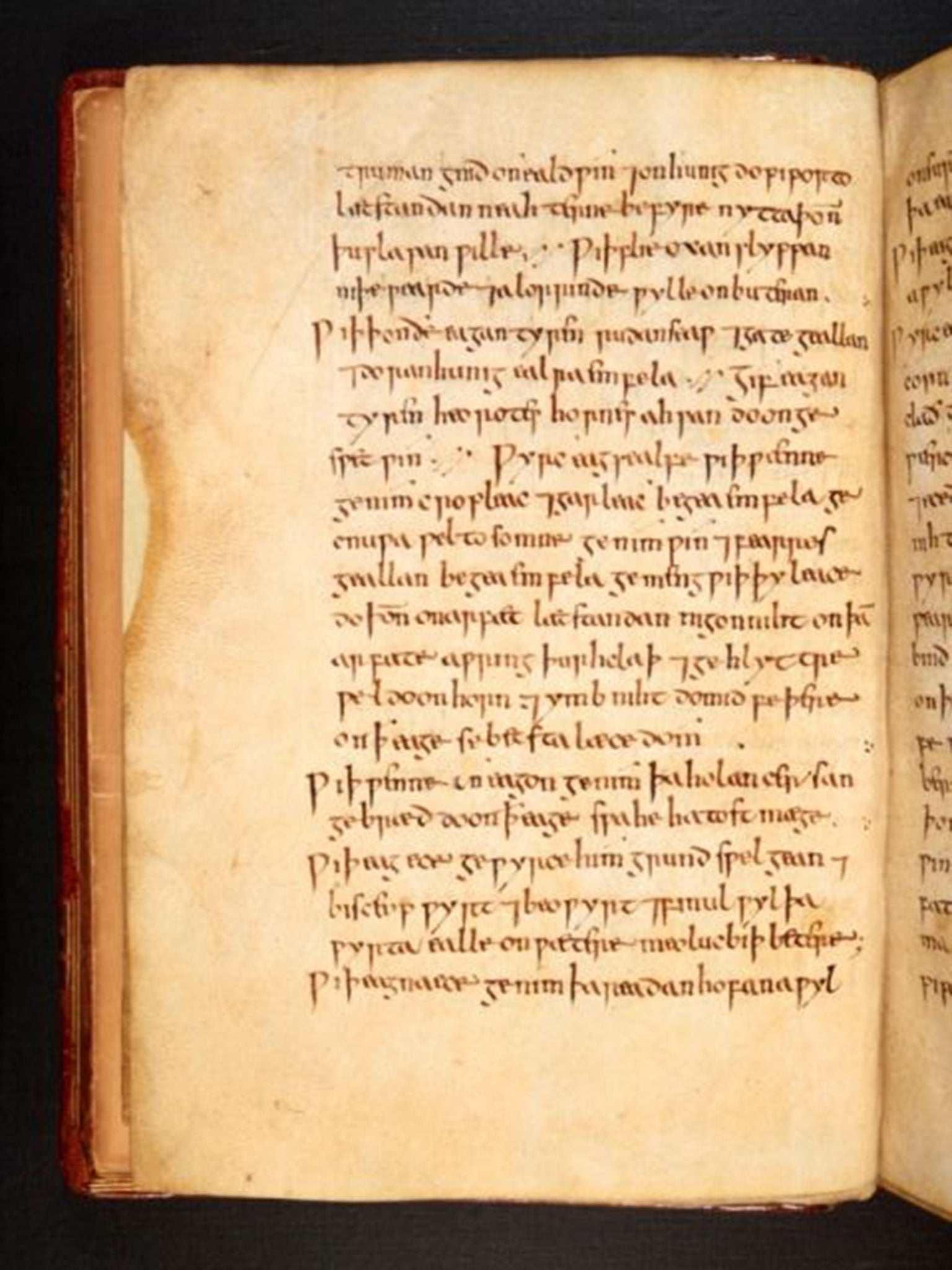

During a meeting of academics interested in infectious diseases, Dr Christina Lee, an expert in Old English, told microbiologists about Bald’s Leechbook – an Anglo-Saxon medical textbook kept in the British Library which contains remedies for treating infections and other ailments.

Dr Lee translated a recipe for treating styes – an infection of an eyelash usually caused by Staphylococcus aureus - and the past year has seen researchers painstakingly recreate it and test it on MRSA.

The thousand-year-old remedy has proven to be an “incredibly potent” antibiotic, according to lead researcher Dr Freya Harrison, a microbiologist from the University of Nottingham.

The individual ingredients alone did not have any measurable effect but when combined according to the ancient text, they killed up to 90 per cent of MRSA bacteria in infected mice. And in infections grown in the laboratory, only about one bacterial cell in a thousand survived.

“I still can’t quite believe how well this one thousand year old antibiotic actually seems to be working, when we got the first results we were just utterly dumbfounded. We did not see this coming at all,” commented Dr Harrison.

The findings will be presented at the Society for General Microbiology’s annual conference in Birmingham tomorrow [Weds] and will be submitted to the global science journal, Nature, shortly.

“Modern research into disease can benefit from past responses and knowledge, which is largely contained in non-scientific writings. But the potential of these texts to contribute to addressing the challenges cannot be understood without the combined expertise of both the arts and science,” commented Dr Lee.

Dr Kendra Rumbaugh, a microbiologist at Texas Tech University who was part of the research team, commented: “These types of wound infections are very difficult to treat, and given that most of the agents we have previously tested displayed little to no efficacy, I was quite skeptical. However, this ‘ancient’ solution performed better than the current ‘gold standard’ (vancomycin) and killed more than 90% of the MRSA in the wounds.”

And this is just the start. For the initial success of the research is prompting scientists to look at nine other recipes from the Anglo-Saxon book.

Responding to the news last night, Professor Laura Piddock, director, Antibiotic Action, said: “It is fascinating that this medieval medicine is able to inhibit the growth of MRSA. Investigation of other old anti-infective remedies may facilitate the discovery of antibiotics that could be turned into treatments for use in the 21st century.”

And Dr Maureen Baker, chair, Royal College of GPs, said: “This fascinating study shows that some of the answers are already out there, and have been used effectively in the past – but looking back and discovering these lost potential treatments will take just as much skill and expertise as developing new ones from scratch. This isn’t going to happen overnight, and will need substantial investment.”

She added: “In the meantime, we need to continue to do what we can, including maintaining excellent hygiene standards, to help stop the spread of superbugs.”

Recipe to treat a stye, translated from Bald’s Leechbook.

“Work and eye salve for a wen, take cropleek and garlic, of both equal quantities, pound them well together, take wine and bullocks gall, of both equal quantities, mix with a leek, put this then into a brazen vessel, let it stand nine days in the brass vessel, wring out through a cloth and clear it well, put it into a horn, and about night time apply with a feather to the eye; the best leechdom.”

Subscribe to Independent Premium to bookmark this article

Want to bookmark your favourite articles and stories to read or reference later? Start your Independent Premium subscription today.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments