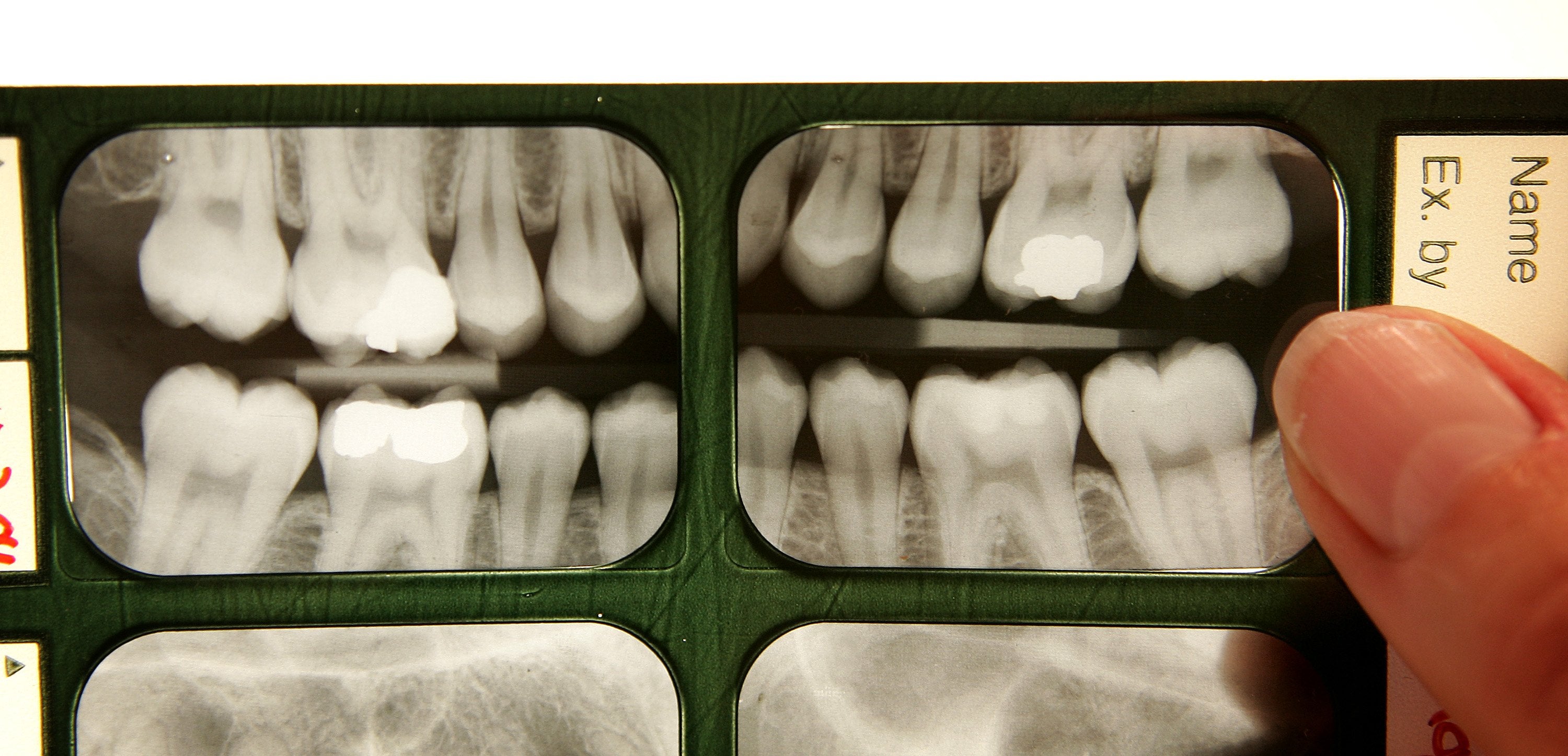

Primate skull study sheds light on why wisdom teeth grow so late in humans

Scientists develop model to explain coordination between facial growth and mechanics of chewing muscles

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Slow body development over the course of life, as well as shorter jaws and retracted faces in humans compared to those in chimpanzees could explain why molar teeth grow much later in people than in our primate cousins, finds a new study.

While chimpanzees get adult molars – the chewing teeth towards the back of the mouth – when they are around three, six and 12 years old, humans grow these at around 6, 12 and 18 years of age, extending into adulthood.

For several decades scientists have known the close link in primates between the pace at which adult molars emerge into the mouth with the overall rate of body development.

Modern humans, according to anthropologists, grow up very slowly and their adult molars emerge very late in life, later than any other living or extinct primate.

“One of the mysteries of human biological development is how the precise synchrony between molar emergence and life history came about and how it is regulated,” study lead author Halszka Glowacka from the University of Arizona said in a statement.

In the current study, published in the journal Science Advances, the scientists analysed primate skulls and developed a model that explains the coordination between facial growth, and the mechanics of the chewing muscles.

Due to a delicate dance between the pace of facial growth and the emergence of the molars, they say these chewing teeth come in only when enough of a “mechanically safe” space is created.

If molars emerge “ahead of schedule”, the researchers say, the teeth would disrupt the fine-tuned function of the entire chewing apparatus and causing damage to the jaw.

They say this understanding can help predict not just the positions in the mouth where adult molars emerge but also when they do so.

Since molars do not emerge until a point when enough facial growth has occurred, the scientists believe “the finer details of the model could be explored in more samples to help understand the phenomenon of impacted wisdom teeth in humans.”

In the research, the scientists created three-dimensional bio-mechanical models of skulls in about two dozen different species of primates ranging from small lemurs to gorillas.

These models also included the attachment positions of each major chewing muscle, throughout the growth period in these primates.

By simulating jaw growth at different rates in each of these primate models, scientists could understand the way in which each of the emerging molars synchronised with the growing and shifting chewing system of the jaw.

“The precise bio-mechanical relationship between growing faces and growing chewing muscles results in the tight and predictive relationship between dental development and life history,” the scientists noted in a statement.

In humans, they say, the delayed molar emergence is a result of the evolution of overall slow facial growth coupled with short jaws and the faces being situated directly beneath our braincase.

“It turns out that our jaws grow very slowly, likely due to our overall slow life histories and, in combination with our short faces, delays when a mechanically safe space — or a ‘sweet spot,’ if you will — is available, resulting in our very late ages at molar emergence,” says Gary Schwartz, another co-author of the study.

The findings, the scientists believe, could help advance the clinical understanding of wisdom teeth.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments