Elusive Peter Higgs and Francois Englert win 2013 Nobel Prize for Physics for work based on Higgs Boson theory

Their theory 'is a central part of the Standard Model of particle physics that describes how the world is constructed'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

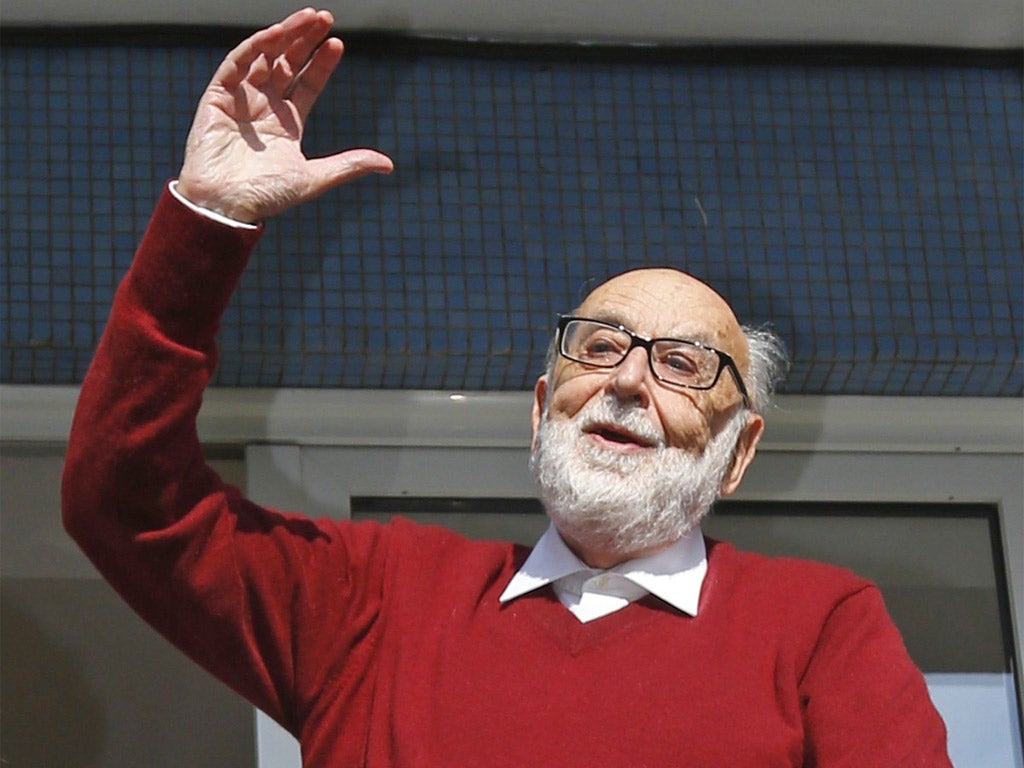

Your support makes all the difference.The search of the elusive Higgs Boson - the subatomic particle that explains why the Universe is how it is - has turned into the search for the missing Peter Higgs, the Edinburgh professor who first proposed the existence of the eponymous particle and who is joint winner of this year's Nobel Prize in Physics.

No-one, including the Nobel Prize committee, seemed to know where Professor Higgs was when the announcement was made in Stockholm that he will share the prize with Belgian physicist Francois Englert of the Free University of Brussels, who independently of Higgs had proposed a similar explanation for the origin of mass nearly 50 years ago.

Several phone calls from the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences to Professor Higgs' home in Edinburgh failed to get through to the 84-year-old retired scientist and even colleagues at the University of Edinburgh, which had prepared a press statement in advance, had no idea where he was.

“I really don't know where he is and my colleague, who knows him better, doesn't know either. I think he decided beforehand not to be around at the time of the Nobel announcement,” said one Edinburgh physicist.

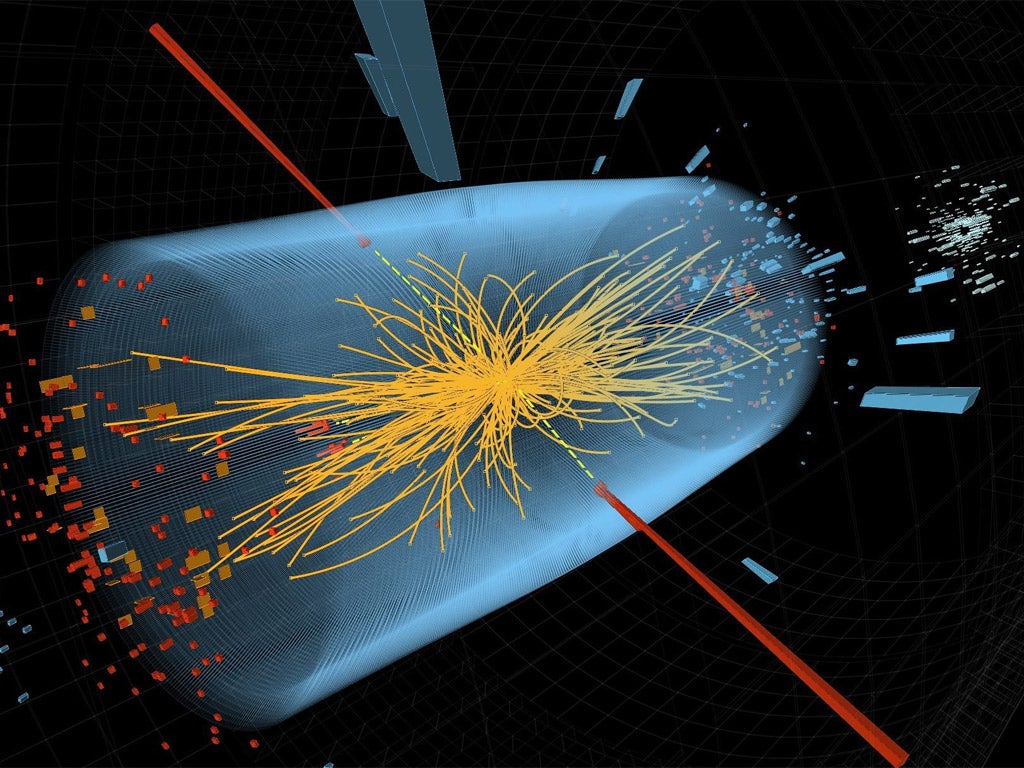

The Royal Swedish Academy, which judged the 8m Swedish Kroner (£776,000) prize this morning in Stockholm, said the two scientists jointly and independently discovered a mechanism that contributes to our understanding of the origin of mass of subatomic particles - now confirmed by experiments attached to the Large Hadron Collider at Cern in Geneva.

The theory proposed by Higgs and Englert is central to the Standard Model of physics which describes how everything in the Universe - from flowers and people to stars and planets - is constructed from just a few buildings blocks or subatomic particles.

“The entire Standard Model also rests on the existence of a special kind of particle: the Higgs particle. This particle originates from an invisible field that fills up all space. Even when the Universe seems empty this field is there,” the academy said.

“Without it, we would not exist, because it is from contact with the field that particles acquire mass. The theory proposed by Englert and Higgs describes this process,” it said.

Congratulations poured in from around the world for the two Nobel laureates, who met for the first time on 4 July 2012 at a meeting at Cern when particle physicists announced that they had found unequivocal evidence for the existence of the Higgs Boson, a sub-atomic particle that could explain why matter has mass and why the Universe therefore has structure.

Perhaps the most poignant message came from Professor Tom Kibble of Imperial College London who could easily have shared the same Nobel Prize for his team's own independent work on the origin of mass, published in 1964 soon after the scientific papers of Englert and Higgs.

“Our paper was unquestionably the last of the three to be published in Physical Review Letters in 1964 (though we naturally regard our treatment as the most thorough and complete) and it is therefore no surprise that the Swedish Academy felt unable to include us, constrained as they are by a self-imposed rule that the Prize cannot be shared by more than three people,” Professor Kibble said.

Another sad omission from this year's prize was Robert Brout, who co-authored the seminal 1964 paper with Englert, but who died in 2011. The Nobel Prize cannot be awarded posthumously.

The announcement from Stockholm was delayed by an hour, perhaps because of the difficulty of finding Professor Higgs, or more likely because there was still intense debate about whether a third individual, or even Cern itself, should also be included in the joint winners.

The only statement from Professor Higgs was one that he had prepared before he knew he had won. “I am overwhelmed to receive this award and thank the Royal Swedish Academy,” he said.

“I would also like to congratulate all those who have contributed to the discovery of this new particle and to thank my family, friends and colleagues for their support. I hope this recognition of fundamental science will help raise awareness of the value of blue-sky research,” he had added.

Meanwhile, Professor Englert said in a live telephone link between Brussels and Stockholm that he was overjoyed to receive the prize, which he had thought he had missed out on because of the unexpected delay in the announcement.

And his message to Professor Higgs when they meet again? “Of course I'm going to congratulate him because I think it's very important and excellent work.”

Atomic particulars

The Higgs boson, a sub-atomic particle that pervades the Universe, is crucial to something called the Standard Model, which attempts to unite the building blocks of matter with three of the four known forces of nature – only gravity is left out.

Until Peter Higgs, Francois Englert and Robert Brout came along with their theory in 1964, the Standard Model was under threat because it could not explain how sub-atomic particles – and hence all matter in the Universe – have mass and therefore structure.

The proposition of a sub-atomic particle that creates a field through which other particles interact was the missing piece of the puzzle. It is this interaction between matter and the field created by the Higgs boson that imparts mass to matter.

Particles that do not interact with this field do not acquire mass which is why photons, or particles of light, do not have mass. Meanwhile, some particles interact weakly with the field and are light while others interact intensely and become heavy.

Higgs bosons, and the field they generate, make the Universe what it is. Without them all matter would collapse because the suddenly massless electrons of atoms would disperse at the speed of light.

Steve Connor

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments