Hidden details of ancient Egyptian paintings revealed by chemical imaging

An international team of scientists has uncovered the changes made to two ancient Egyptian paintings.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Portable technology can reveal hidden details in ancient Egyptian paintings, research suggests.

An international team of scientists has uncovered the alterations made to two ancient Egyptian paintings (dating to approximately 1,400 and 1,200 BCE, respectively) in details invisible to the naked eye.

The language of ancient Egypt has no known word for ‘art’, and the civilisation is often perceived as having been extremely formal in its creative expression.

This is also true of the works completed by the painters of its funerary chapels.

These discoveries clearly call for a systematised and closer inspection of paintings in Egypt using physicochemical characterisation

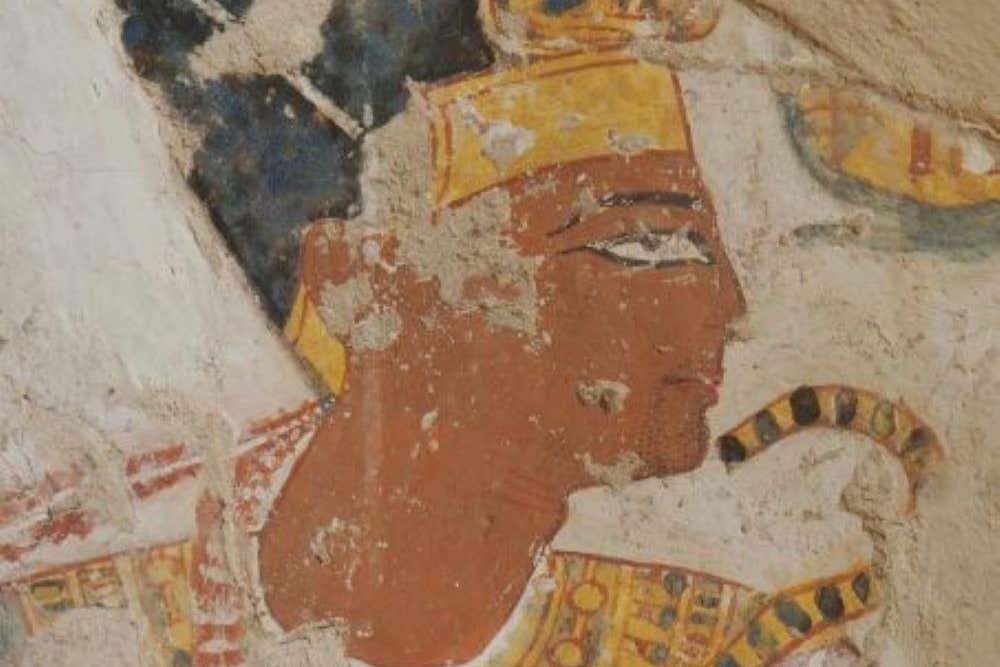

However, the new study reveals one painting in which the headdress, necklace, and sceptre in the image of Ramesses II were substantially reworked.

And in a scene of adoration depicted in Menna’s tomb, the position and colour of an arm were modified.

The pigments used to represent skin colour differ from those first applied, resulting in subtle changes whose purpose still remains uncertain.

The findings suggest these painters, or draughtsmen-scribes – at the request of the individuals who commissioned their works, or at the initiative of the artists themselves as their own vision of the works changed – could add their personal touches to conventional motifs.

While most studies of Egyptian artwork take place in museums or laboratories, in this study researchers used portable devices to perform chemical imaging on paintings in their original context.

This allowed for analysis of paint composition and layering and for the identification of alterations made to ancient paintings.

Both of the paintings analysed in detail were located in tomb chapels in the Theban Necropolis near the river Nile, dating to the Ramesside period.

On the first painting, researchers were able to identify alterations made to the position of a figure’s arm, though the reason for this relatively small change is uncertain.

While on the second painting, the researchers uncovered numerous adjustments to the crown and other royal items depicted on a portrait of Ramesses II.

It is suggested that these changes most likely relate to some change in symbolic meaning over time.

Such alterations to paintings are thought to be rare among such art, but the researchers suggest that these discoveries call for further investigation.

Many uncertainties remain about the reasoning and the timing behind the alterations observed, some of which might be resolved by future analysis.

The study authors said: “These discoveries clearly call for a systematised and closer inspection of paintings in Egypt using physicochemical characterisation.”

The research, published in the Plos One journal, was conducted by Philippe Martinez of Sorbonne University and scientists from the Centre national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS), and Universite Grenoble Alpes.