Researchers find new ways female bones permanently change after giving birth

The study found that calcium, magnesium and phosphorus concentrations are lower in females who have given birth.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Giving birth changes females’ bones in a way that was not previously known, new research suggests.

Analysis of monkeys, sheds new light on how giving birth can permanently change the body.

Specifically, the researchers found that calcium, magnesium and phosphorus concentrations are lower in females who have given birth.

These changes are linked to giving birth itself and to breastfeeding.

Our findings provide additional evidence of the profound impact that reproduction has on the female organism, further demonstrating that the skeleton is not a static organ, but a dynamic one that changes with life events

Paola Cerrito, who led the research as a doctoral student in New York University’s (NYU) Department of Anthropology and College of Dentistry, said: “Our findings provide additional evidence of the profound impact that reproduction has on the female organism, further demonstrating that the skeleton is not a static organ, but a dynamic one that changes with life events.”

The researchers caution that while other studies show calcium and phosphorus are necessary for optimal bone strength, the new findings do not address overall health implications for either primates or humans.

Instead, they say the work highlights the dynamic nature of our bones.

“A bone is not a static and dead portion of the skeleton,” added NYU anthropologist Shara Bailey, one of the study’s authors.

“It continuously adjusts and responds to physiological processes.”

Researchers say that while it has been long-established that menopause can have an effect on females’ bones, it has been less clear on how preceding life-cycle events, such as reproduction, can influence skeletal composition.

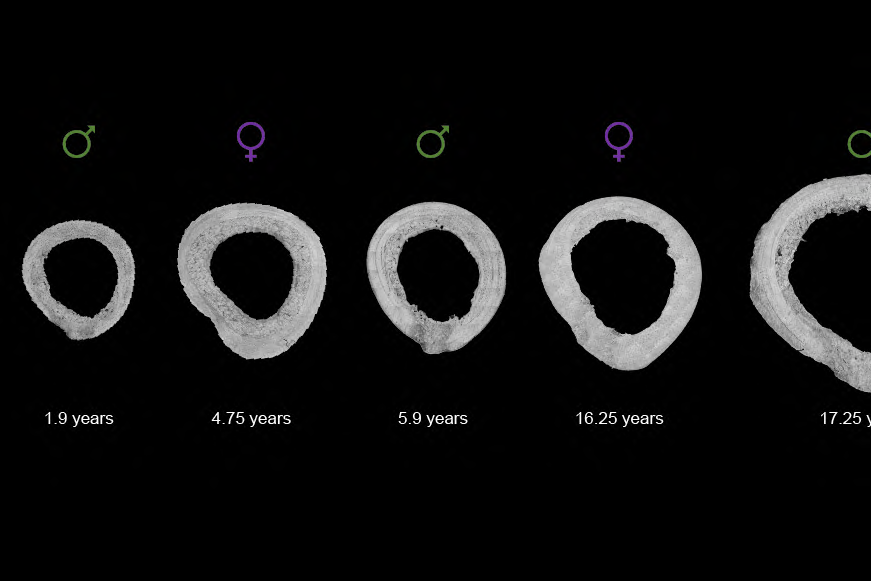

To address this, they studied eight thigh bones.

Because this aspect of the skeleton changes over time and leaves biological markers of these changes, it is an ideal part of the body to examine, allowing scientists to monitor alterations throughout life.

The scientists used technology commonly used to gauge the chemical composition of tissue samples to calculate changes in concentrations of calcium, phosphorus, oxygen, magnesium and sodium in the primates’ bones.

The findings showed different concentrations of some of these elements in females who gave birth compared to males as well as females who did not give birth.

Specifically, in females who gave birth, calcium and phosphorus were lower in bone formed during reproductive events.

There was also a significant decline in magnesium concentration during these primates’ breastfeeding of infants, the study suggests.

Professor Cerrito said: “Our research shows that even before the cessation of fertility the skeleton responds dynamically to changes in reproductive status.

“Moreover, these findings reaffirm the significant impact giving birth has on a female organism – quite simply, evidence of reproduction is ‘written in the bones’ for life.”

The findings are published in the Plos One journal.