New Year’s Eve: The scientific reason why it is generally terrible

Those who plan to have a great time on New Year's Eve are likely to be the most miserable of all

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the movies, New Year’s Eve is always full of excitement and intrigue, attractive people in sparkly outfits, and surprise kisses at midnight. So why does real-world New Year’s Eve always seem to consist of losing your friends in a crowded bar, standing in line forever for drinks, and waiting an hour in the cold for a ridiculously priced Uber?

Research done by a team of psychologists and economists on how we experience happiness actually offers an explanation. In a 1999 study called “The pursuit and assessment of happiness can be self-defeating,” Jonathan Schooler, now of the University of California Santa Barbara, Dan Ariely of Duke University and George Loewenstein of Carnegie Melon offer evidence that those who plan to have a great time on New Year's Eve are likely to be the most miserable of all.

In the weeks leading up to New Year’s Eve, the researchers surveyed 475 people about their plans for the night – whether they would celebrate, how big the party would be, how much time and money they would spend on the preparation, and how much they expected to enjoy it. Then they contacted the same people several weeks after New Year’s Eve and asked them the same questions again.

The study found that an overwhelming 83 percent of those they surveyed ended up being disappointed with their New Year’s Eve celebration. And the people who were the most let down were those with the highest expectations.

Those who were expecting to attend a big party on New Year’s Eve ended up being the most disappointed, followed by those who planned a small party, followed by those who had no plans to celebrate. Similarly, those who had anticipated enjoying New Year’s Eve and expected to spend time on preparations for the event were significantly more likely to say they were disappointed afterwards.

The researchers can’t be sure just why this happened. However, another study they did around the same time supports the idea that trying to feel happy is one of the quickest ways to undermine your own experience.

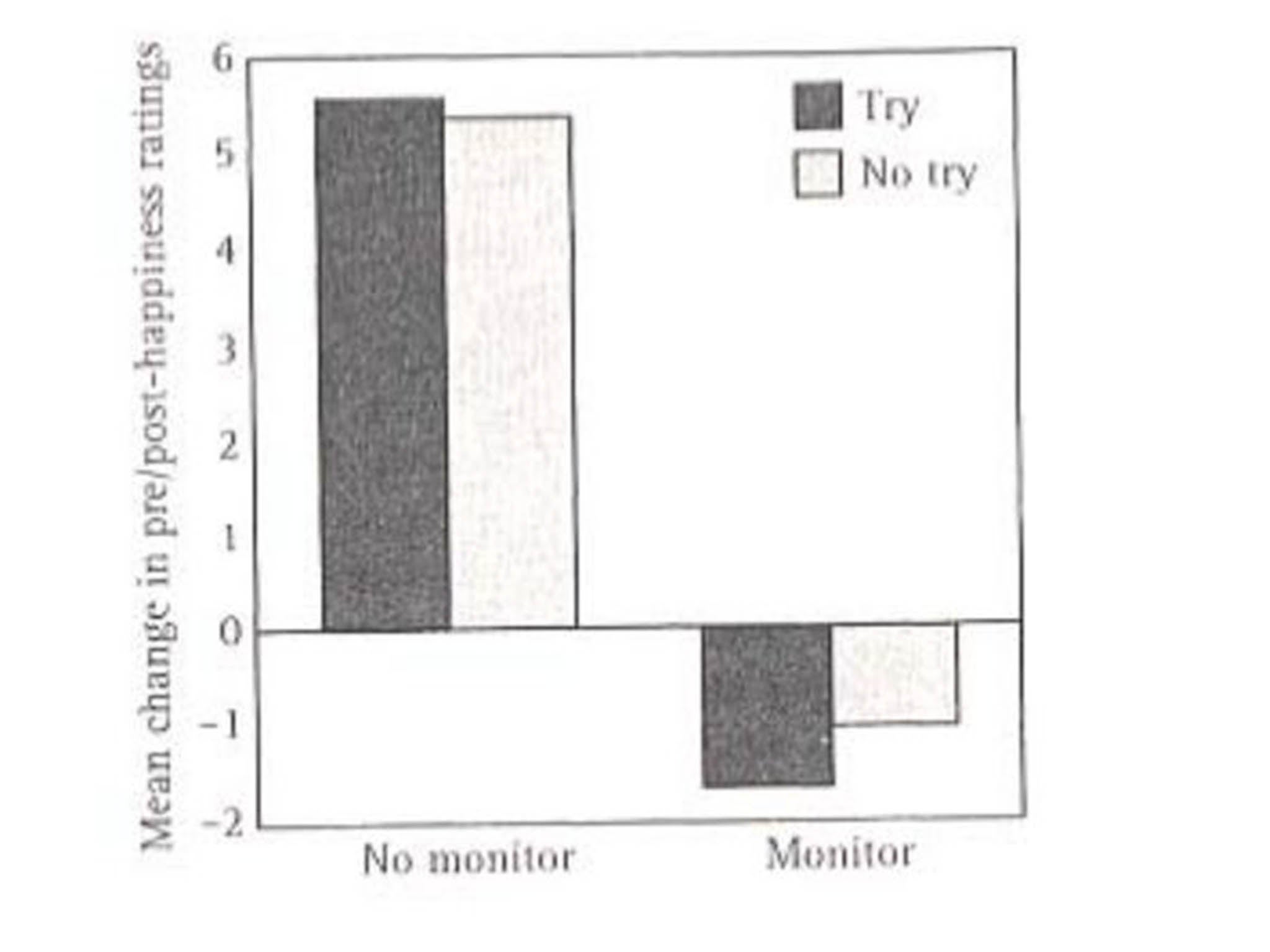

In that experiment, Schooler, Ariely and Loewenstein had students listen to a famous piece of music – Stravinsky’s “The Rite of Spring” – and then record their levels of happiness. Some of the students were told to try to feel happy during the music, and others were not. Some were asked to check in during the listening period to see how happy they felt at the moment, while others were just asked to assess their happiness at the end.

Their data showed that students who tried to be happy and who checked periodically to see whether they were actually happy reported the lowest levels of happiness of all, as the graph below shows.

The researchers compare this idea to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle in physics, which says that in trying to measure a particle’s energy we influence its energy level. In a similar way, trying to measure whether we're happy appears to change our levels of happiness.

The researchers aren’t sure whether those who had high expectations for New Year’s Eve ended up disappointed because they were trying to be happy and monitoring their emotions that night, but they say the assumption is plausible.

Why does this happen? The researchers say it could be because monitoring your happiness actually takes your attention away from the activity, overshadowing and detracting from the experience. And it's also likely that having high expectations for happiness may encourage someone to make unfavorable comparisons between what they experience and an imagined, ideal state of happiness, which can lead to frustration.

Psychological research done in the decade and a half since this study supports the idea that the pursuit of happiness is paradoxically self-defeating. In a study published in 2011, Iris Mauss of UC Berkeley found that women who valued happiness more reported lower happiness when under conditions of lower life stress.

Past studies have also shown that people who are chronically happy are less introspective, and that people who are chronically unhappy are more self-conscious and self-focused. Studies on happiness and selfishness show similar results: Selfish people are more devoted to their own happiness, but appear to be less happy overall.

The researchers say their findings about New Year's Eve aren't a call for abandoning parties and reflection, just for managing your expectations and focusing on savoring your experiences when you're having them.

Schooler, the lead author of the study, points out that psychological studies describe trends, not individual experiences. “Even in our study, even though there was a trend for people having bigger bashes to be more disappointed, there were plenty of people who expected a big bash and had a good time,” he says.

But it’s certainly an argument for not over-thinking it — and for not feeling guilty if you'd rather spend New Year's Eve at home in your pajamas.

Copyright: Washington Post

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments