New parasitic wasp species discovered in Norway

Species learns ‘language’ of other wasps, or bees, before laying eggs in their nests, which eat any other eggs and larvae in the nest

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A new species of parasitic wasp, which lays its eggs in other bee and wasp nests where their larvae hatch and eat their hosts’ developing offspring, has been discovered in Norway.

The species belongs to a group of insects known as cuckoo wasps, due to their underhand child-rearing methods similar to the birds.

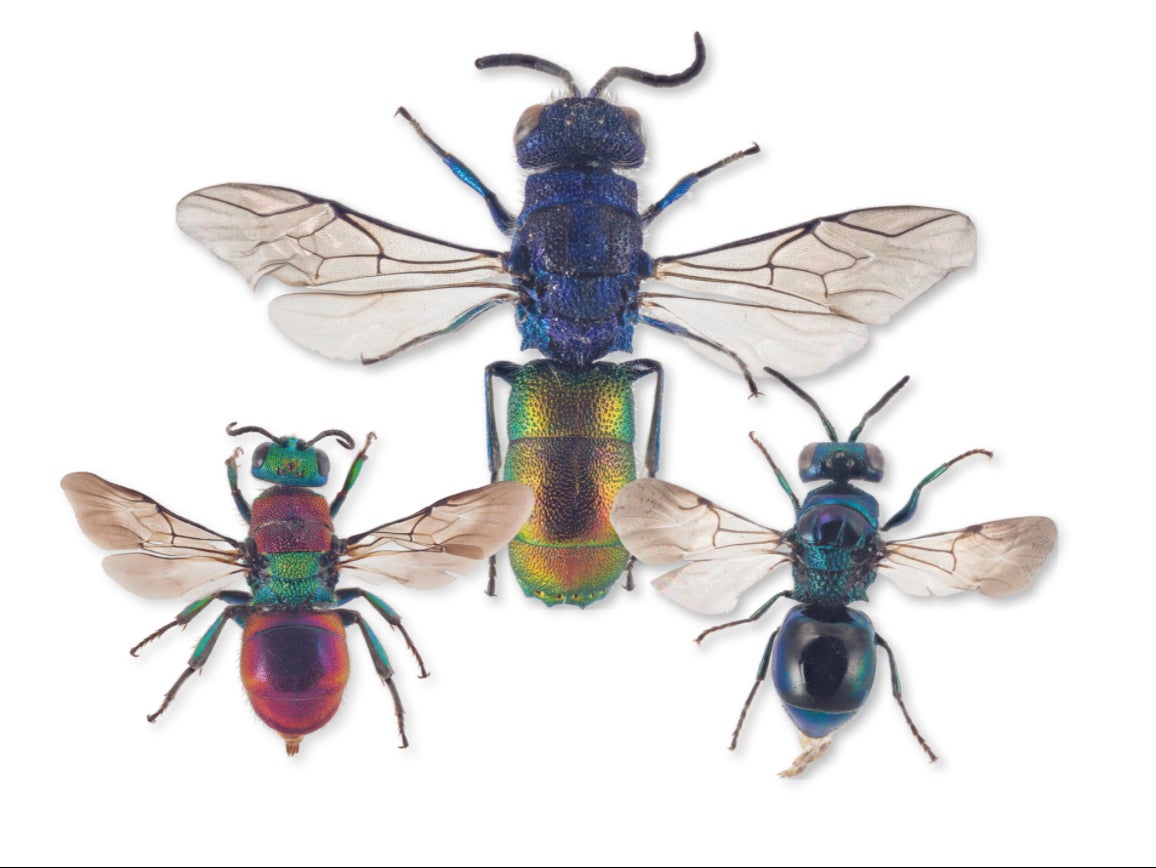

They have brightly coloured iridescent carapaces that shine like jewels, and they are also known as emerald wasps, but due to their physical similarities it has been very difficult for etymologists to distinguish some species.

New DNA coding techniques have allowed scientists to definitively tell the insects apart for the first time, helping to lead to the discovery of the species.

Frode Ødegaard, an insect researcher at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), said: “Normally we distinguish insects from each other by their appearance, but cuckoo wasps are so similar to each other that it makes it difficult.”

Read more:

- Extinction Rebellion announces ‘wave’ of action against banks over fossil fuel investments

- Pollution from Europe’s coal plants responsible for ‘up to 34,000 deaths each year’

- Climate activists divided over whether Cop26 should still go ahead if online only

- Bitcoin mining is disastrous for the environment – it is time for governments to intervene

- Welcome to Dunbar, Scotland’s first zero-waste town

The research team at the university said the new species is very rare, and that only a single specimen has been found on the Lista peninsula in Agder county in southern Norway.

For more than 200 years, researchers have struggled to sort cuckoo wasps into the right “species boxes” and to determine which characteristics are variations within a species and which are species-specific differences.

But over the last decade DNA barcoding has brought about a major breakthrough by making it possible to distinguish different species of cuckoo wasps from each other by looking at the differences in their genetic material.

"But it’s not always that easy, either,” said Dr Ødegaard. “In this case, we had two cuckoo wasps with microscopic differences in appearance and very small differences in DNA.

“The next step was to look at the language of each of the wasps to find out if they belonged to different species.”

The wasps communicate with each other through pheromones – which the researchers said was like a chemical language.

Very closely related species often have completely different pheromone languages to prevent them from interbreeding.

But the cuckoo wasp has above-average linguistic abilities, which they put to devastating use in order to succeed in getting host species to rear their young.

The parasitic species behaves like cuckoos – laying their eggs in the nests of bees and other wasps. The larvae grow quickly and hatch before the host’s eggs. Then they eat the eggs, the larvae and the food supply that the host has arranged in the nest.

“When you live as a parasite, it’s important not to be discovered, and therefore the cuckoo wasp has also learned the language of its host,” said Dr Ødegaard.

By conducting what the researchers described as “an ever-so-small language study”, the scientists discovered that the two almost identical cuckoo wasps did indeed belong to different species. They use different hosts – and that means that they also speak completely different languages.

“The evolutionary development associated with sponging off another species happens very fast. That’s why you can have two species that are really similar genetically but still belong to different species,” said Dr Ødegaard.

When a new species is described it has to be given a name, and Dr Ødegaard had the good fortune to receive the honour of naming the newcomer.

“A naming competition was announced among researchers in Europe who work with cuckoo wasps, and then the proposals that came in were voted on. It turned out my proposal actually got the most votes!” said Dr Ødegaard.

“As mentioned, the new wasp is very similar to another species called Chrysis brevitarsis, so the new species was named Chrysis parabrevitarsis, which means ‘the one standing next to brevitarsis’.”

Dr Ødegaard was also responsible for giving the species its slightly simpler Norwegian name of sporegullveps. He makes no secret of the fact that he found it great to be able to name a new species.

“In a way, you place yourself in the perspective of eternity, because that species will always have that name,” he said. “There’s something very fundamental about it.”

The only known specimen of this cuckoo wasp has been captured and pinned in an insect collection, the researchers said.

“Even with today’s advanced methods, using live animals for studies like this isn’t possible, but collecting individual specimens fortunately has no impact on the population,” Dr Ødegaard said.

“The insects have enormous reproductive potential, and the size and quality of the habitats are what determine the viability of the population, not whether any specimens are eaten by birds or collected by an insect researcher.”

He said the collected insects are absolutely crucial for researchers to be able to map and describe their diversity and thus take care of viable populations for posterity.

The research is published in the journal Insect Systematics and Diversity.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments